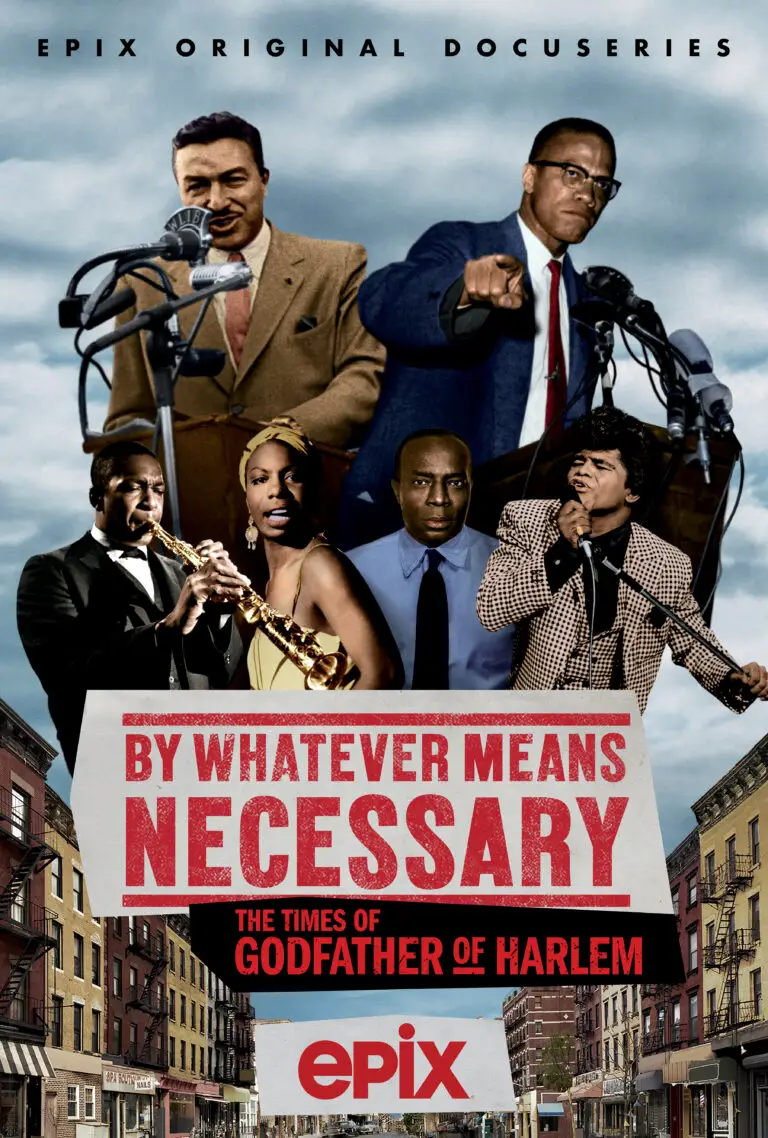

With the May premiere of Laurel Canyon, its two-part series dedicated to the California rock of the ‘60s and ‘70s, EPIX proved it might just be TV’s best new source for music documentaries. With its latest effort, By Whatever Means Necessary: The Times of Godfather of Harlem, EPIX is heading East and uptown. The mission here is to spotlight the many musicians and the musical genres they birthed, from soul, funk and jazz to boogaloo and proto-rap, that helped inspire social change during the turbulent 60s, in New York City’s most culturally percolating neighborhood.

This four-part series is the counterpart to Godfather of Harlem, the acclaimed period drama featuring Forest Whitaker and Giancarlo Esposito. This Emmy Award-winning series follows the story of Bumpy Johnson, the notorious Harlem gangster who sought his own version of economic empowerment against the Italian mob, in an era when Black men and women had little power or choices for upward mobility. The action of the series spans the decade and is fueled by a soundtrack featuring the best of this very best era of Black music.

The fascinating story of this golden era is told in interviews with musicians like Martha Reeves, Gladys Knight, Herbie Hancock, Carlos Alomar, Nile Rogers, A$AP Ferg, Chika, Gary Bartz and Joe Bataan, along with the activists who were there pushing forward the drive for civil rights like Al Sharpton. It also contains a remarkable bounty of rarely-seen archival footage, of interviews and live performances by giants like John Coltrane, James Brown, Gil Scott-Heron and many more.

NYS Music speaks here with Keith McQuirter, the series’ Executive Producer and Director about what viewers can expect with the premiere of this series, November 8 at 10 pm ET/PT.

Sal Cataldi: The EPIX dramatic series for which your documentaries are a companion, Godfather of Harlem, is set in the ‘60s in NYC, a time and place of incredible change and musical innovation. Why was music so interweaved with and reflective of the currents of that particular time and place, the civil rights movement and the like?

Keith McQuirter: What drew me to do this series was to examine how music was used as a force for good in the fight for civil rights. There is a long history of Black protest and empowerment music and our series looks at the years, from 1960 – 1969, from the point-of-view of Harlem residents. The scripted series, Godfather of Harlem, is really a civil rights story, told in the criminal underworld. Our series focuses on an entirely different palate – how music impacted culture and politics, and how culture and politics impacted the music. It allows audiences to see the national story of the Black freedom struggle through the personalities, music and activism coming out of Harlem.

Harlem was a very political place in the ‘60s. Many black families fled the south due to racial terrorism and sought better economic opportunities, only to be face racism, discrimination, limited opportunity and segregated schools in the New York City. You had dueling philosophies of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. and the megawatt influence of Adam Clayton Powell Jr, who was both a Baptist minister and congressman representing the neighborhood. You had the Garveyites, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords and some many others in the fight for civil rights. Not everyone agreed on the approach, but they all agreed that it was time for a change. The freedom songs coming out of the Black church, the jazz of John Coltrane, Charlie Mingus, Max Roach and even Chubby Checker’s Twist spoke to power and change. Our series brings it all together through interviews with eyewitnesses, luminaries and archival that gives a unique look at this part of Black history and culture that is rarely ever told.

SC: The first episode spotlights The Apollo Theater, with comments from performers like Martha Reeves of Martha and the Vandellas and Gladys Knight, and even actor Giancarlo Esposito, one the stars of Godfather of Harlem who saw performances there as a child. What are some of the more interesting things you uncovered about the Apollo in your interviews and research?

KM: The Apollo Theater has been a cultural bedrock in Harlem and America for decades. If you wanted to be a star on the national stage, performing at the Apollo was a rite of passage for many artists. So all the greats performed on the Apollo stage. We spoke with Martha Reeves and Gladys Knight, who told us about her first time performing at the Apollo at a very young age. Both she and Martha talked about how nervous they were because the Apollo audience is known to be a tough crowd. If you get booed off, you might get a tomato thrown at you or other unpleasant things. It was interesting to learn the origin stories of these two legends.

But there is a lesser known story that I appreciated. In the late 1960’s, the Apollo Theater had a mentorship program, where they developed and groomed underprivileged, musically talented teens to be professional entertainers. The teens formed a band under the direction of the theater called Listen My Brother, in which 17-year-old Luther Vandross was a member. We interviewed Carlos Alomar of David Bowie Band fame and Robin Clark, both members of the band. They met as teens during the Apollo program and married before their 20th birthdays. Fifty years later, they are still married! It’s a truly musical love story. Their homework was to go upstairs and watch the Supremes and the Temptations — study their grooming, choreography, stage presence and incorporate it into their rehearsals and their own performances. Can you imagine that type of education? Robin Clark shared about how one day Aretha Franklin came down to the basement where they were rehearsing and talked to the teens about the music business. Robin said she couldn’t believe her idol casually made a surprise visit to their rehearsal. Its apparent that the education and mentorship paid off because both Robin Clark and Carlos Alomar have had illustrious careers in the music business for decades.

SC: The series illustrates how jazz, and especially the new breed of free jazz musicians, were reflecting the civil rights movement. How did the works like John Coltrane’s “Alabama” and Max Roach’s “Freedom Now Suite” energize the drive for equality?

KM: John Coltrane’s “Alabama” is a haunting elegy for the four little girls who died in the Birmingham church bombing in 1963, that was recorded just two months after the tragedy, when grief still weighed heavily on people’s hearts. Coltrane modeled the piece after Martin Luther King’s eulogy to the four girls that was delivered three days after the bombing. The saxophone begins in a tone and cadence of profound mourning, and gradually gains complexity and intensity, expressing the steady resolve to continue the struggle against racist brutality. The message in Coltrane’s piece remains relevant today, with racially-motivated violence still threatening the lives of Black people.

I also interviewed Warren Smith the legendary percussionist, who played with so many greats like Miles David, Aretha Franklin, Janis Joplin, Nina Simone and Max Roach. He says that Coltrane was unafraid to express his emotions in ways that were new at that time. He inspired Smith and others to fully lay into their instruments to express their anger and to say something meaningful.

This was in contrast to when most pop music at that time still avoided addressing political and racial issues, in an explicit way. Many jazz artists were fearless about expressing Black rage and resistance through their music. Jazz was the perfect vehicle for conveying the message of resistance, since the genre is deeply rooted in the historical Black experience. So, Max Roach’s “Freedom Now Suite” was a celebration of emancipation and the years of struggle that followed the end of slavery.

The incredible vocalist Abbey Lincoln expressed the anxiety and anticipation of emancipation against a frenetic avant-garde rhythm section. Roach said in an archival interview we found that, “We could never finish the song because we don’t really know how it feels to be free.” We also interviewed jazz saxophonist Gary Bartz, who played with Roach on the “Freedom Now Suite” and he remembers when he found out that the record was banned in South Africa – clear evidence that music could be a weapon for change.

SC: Curtis Mayfield was especially important, as a musical messenger, a sort of pop music poet of the struggle. What was it about him that connected so strongly with the movement and which resonates today?

KM: Curtis Mayfield had come up in doo wop music, collaborating with his old friends from Chicago’s Cabrini Green housing projects. As an artist, he understood the power of music to uplift and empower. He focused on building a viable music career and began to write songs that sent an implicit message of hope to young Black people hungry for change. His song, “It’s All Right,” speaks directly to the young people:

“When you wake up early in the morning, feeling sad like so many of us do, Hold a little soul, and make life your goal, and surely something’s got to come to you. And you’ve got to say, It’s all right…”

The song launched Mayfield’s career and his band, The Impressions, and it captured the spirit of resistance and hope that characterized the beginning of the decade. He later released “Keep on Pushing” capturing the civil rights movement determination for change. There were many artists providing the soundtrack to the civil rights era, but Mayfield is prominent because his music always deliver the message of empowerment.

By the end of the decade, his music had come a long, long way. His lyrics had become explicitly political, and his sound was funkier and more soulful. He released “(Don’t Worry) If There’s Hell Below, We’re All Going To Go” where he calls out the courts and the police as political actors, talks about the drug epidemic and pollution and how all of this decay and corruption is going to bring us all to our downfall. This message juxtaposed to Richard Nixon’s who was just elected president by an overwhelming white conversative calling for law and order and a return to the old America. It all sounds incredibly familiar.

SC: James Brown is another giant highlight in the series, especially the role he played in black pride, in actually changing the racial terminology from “Negro” to “Black” with his anthem “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” How powerful an impact did this song have in the community?

KM: In the late 60’s, James Brown released an unexpected anthem, “Say it Loud (I’m Black and Proud).” This song made James Brown one of the most prominent performers to celebrate Black identity. Ever since his historic live album recorded at Harlem’s Apollo Theater in the early 60’s, Brown had personified unadulterated, unapologetic blackness. But his lyrics had always avoided politics, and his personal style still reflected an earlier time – especially his hair, which he kept in a carefully-maintained pompadour. By the time this came out, Brown cut his hair and sported an Afro in message with the changing time.

Brown later complained that “Say It Loud” ultimately cost him record sales, radio play and bookings at white clubs; but, at the moment it came out, it was an instant hit. Brown’s words were also taken up by activists across the country, who were marching in a never-ending series of protests – against the war in Vietnam, inferior schools, irresponsible landlords, unfair practices, and all the other problems the community still faced. His music fueled Black resistance and allowed Black folks to freely celebrate themselves and their culture with pride.

SC: How did The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron, the pioneers of the fusion of poetry into music, impact their times and ours today?

KM: In our series, we interview Felipe Luciano who talks about his trajectory into revolutionary culture. He was a kid who grew up in Spanish Harlem of Puerto Rican origin, but he consider East Harlem his homeland – not just his birthplace, but the place that made him who is today.

Luciano says that he felt lost when he got out of prison in 1966, but he found his purpose when he met other young Nuyoricans who were developing a radical new political consciousness, inspired by their Black friends engaged in the freedom struggle. He had studied Puerto Rican history while in prison, read the writings of Pedro Albizu Campos, trying to understand why his parents’ generation gave up on statehood and accepted the humiliation of being ‘colonized’ by the U.S.

Activism gave him hope. He was excited by the emergence of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense on the West Coast, and the bold call for Black Power from Stokely Carmichael, a New York-raised activist of Trinidadian origin. He decided it was time for Latin people to work for radical change too. When he heard about the opening of a New York chapter of the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican organization modeled on the Black Panthers, he got involved immediately.

So by the time Luciano became a member of The Last Poets in the late 60’s, he was already a leader in the Young Lords and was a revolutionary. When you hear the music of The Last Poets, accompanied by African-inspired Congo drums, it make sense they were so incredibly free to express themselves, in ways most people just didn’t at that time. They spoke truth to power, but also they just spoke truth, often in incendiary ways, but it freed people to be able to express themselves without barriers or shame.

In an interview, the jazz saxophonist Gary Bartz said it was like a secret language that he and others understood deeply, but not everyone could relate. Hip Hop can be that way too, in that it is specific to a group or even a neighborhood and is not always inclusionary. Luciano believed poetry was just as important as marching in the streets. You see this same reverence for lyrics in young artists today – Kendrick Lamar, CHIKA, Janelle Monae and so many others — they are reflecting the times, giving empowerment and allowing us to be free to be ourselves. The Last Poets showed us freedom of expression in words, and its fitting that they have the designation as being called “The Fathers of Hip Hop.”

SC: The series doesn’t just focus on Black artists but the Latinos of Harlem who forged their own kind of music of celebration and liberation. Tell us about some of them, especially the pioneers of boogaloo?

KM: East Harlem, nicknamed ‘El Barrio,’ became the capital of Puerto Rican culture in the mainland U.S. And although Puerto Ricans became American citizens in 1917, in the U.S. they were still seen as foreigners.

In the ‘60s Spanish-speaking migrants were the majority of the neighborhood’s population, but many of them struggled with poverty, unemployment, and racial discrimination. The language barrier made it difficult to find decent, well-paid jobs, or navigate government agencies. This generation found comfort in the music from back home, and bandleaders like Tito Puente and Tito Rodriguez reigned supreme at the city’s biggest Latin club, the Palladium Ballroom in midtown.

Miguel “Mickey” Melendez, an East Harlem resident, and a member of the Young Lords who we interviewed in the series, spoke about the American-born children of Puerto Rican migrants were growing up as Harlem teenagers, and their day-to-day experiences – and the music they loved – were completely different from those of their parents. These kids went to school with African-American classmates, hung out with African-American friends and neighbors, and danced to doo-wop, soul, and R & B. They would create a new genre of music that gave voice to the intersection of Black and Latin culture — boogaloo, the soul of El Barrio.

Denise Oliver-Velez, another member of the Young Lords, talks about Joe Cuba’s “Bang Bang,” a song, composed spontaneously at a ‘Black dance’ night at the Palm Gardens Ballroom, was one of the first boogaloo songs to launch the craze that swept New York, and then the world of Latin music. It combined English and Spanglish lyrics with an R & B rhythm on timbales and melodic piano, and immediately inspired a wave-style dance. Within weeks, the Joe Cuba Sextet recorded and released “Bang Bang” as a single, and it became one of the most successful Latin recordings to cross over to mixed audiences, selling over a million copies.

When Joe Bataan got out of prison, he tells the story about how desperate he was to achieve his dream of becoming a musician. He had the reputation of being a gangster at that time and would sneak into a local school to play the piano. One day, he discovered a group of musicians using ‘his’ practice space, so he stuck a knife in the piano and told them that from then on, they would be his band. He wanted to make a name for himself and hoped that music would save him from the cycle of gang violence and incarceration.

After a debut recording that went nowhere, Bataan’s first hit was a boogaloo cover of the Curtis Mayfield ballad “Gypsy Woman,” spiced up with Latin percussion and an irresistible hook. All the band members were shouting “She smokes!”. Bataan remembers how, in 1966 and 1967, you could hear boogaloo echoing throughout the neighborhood – and how proud he was, coming from the streets, to representing his neighborhood in a way everyone could celebrate.

For Felipe Luciano, Boogaloo was more than just party music. It was an expression of Nuyorican identity, giving voice to their generation’s rage against the discrimination their parents had faced, and demonstrating their deep connection to the Black struggle. In its own way, boogaloo was a music of defiance against ghetto life and the elusiveness of the American dream.

SC: The series contains so much remarkable archival footage that is largely unseen. What are some of your own favorite moments of the musicians on film that you unearthed?

KM: For a nerd like myself, archival research is a fascinating, deep dive exploration that can take you on many adventures. Finding archival of Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln performing “Driva’ Man” and “Triptyh: Prayer / Protest / Peace” from the “Freedom Now Suite” is like finding gold. I could not stop watching it over and over again.

I also enjoyed unearthing Apollo performances from Martha and Vandellas and other Motown acts. To see these entertainers as teenagers in archival footage, who I’ve known my whole life to be legends and then getting to interview them too, it was just incredible. Artists like Herbie Hancock and Gladys Knight are of my parent’s generation, so their music was always a part of the soundtrack of my life.

I really love the archival we found of the Last Poets performing “Hey Now” and “Jibero, My Pretty N****. “ New York indie filmmaker Herbert Danska filmed them on a Harlem rooftop for his film Right On! A film that screened at the Director Fortnight in the 1970 at the Cannes Film Festival. It shows three Black men on a rooftop – Felipe Luciano, David Nelson and Gylan Kain – with a percussive accompaniment performing poetry. It’s rough, raw, and a bit strange. It’s truly great stuff.

SC: The ‘60s were a pretty special time, an era where music really helped, as Giancarlo Esposito says in the series, becoming “the force that gave the people strength.” Do you think music has the same impact today?

KM: Every time I visit a Baptist church and sing those old songs that my grandparents and great grandparent sang, I feel uplifted, and some of those songs have been around for hundreds of years.

Music is healing, empowering and motivating. It reenforces the stories of our lives and reflects our dreams, hopes and ambitions. Music is culture. And, culture is inherently political. This year has seen a proliferation of protest music by known and unknown artists. It’s a tradition that has been passed down generationally and young people are making it their own, especially through the use of social media. Most of the musicians I spoke to for this series have expressed how inspired they are by activism happening today in music. The work from the ‘60’s civil rights movement never ended because we still are facing police brutality in our communities, disparities in healthcare, massive incarceration and gun violence – we have so much work to do. The musicians have a role in providing us and generations of activist to follow soundtracks that empowers, uplift, affirms our identity and our humanity.

Comments are closed.