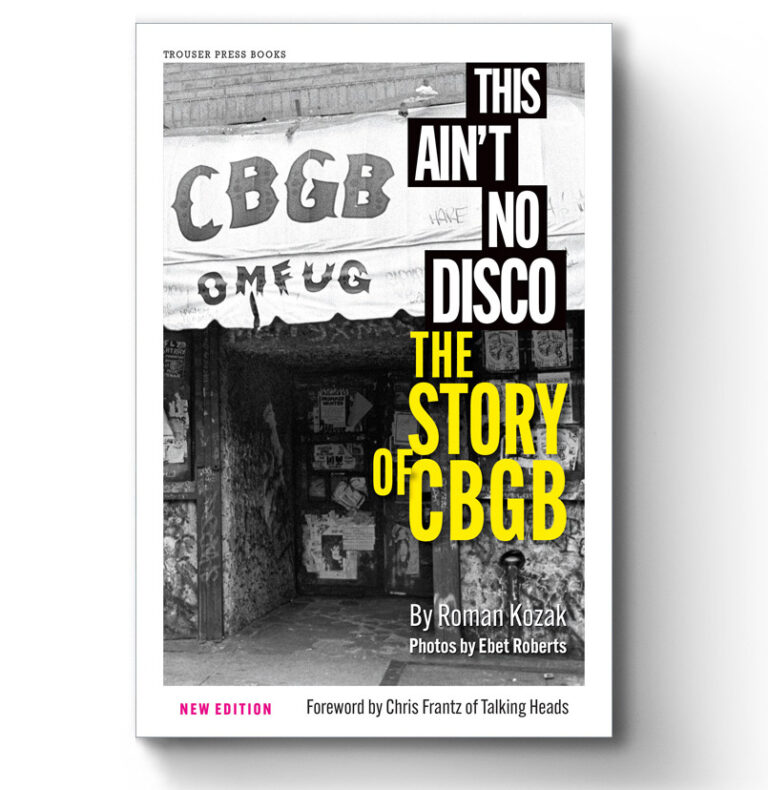

The first and most comprehensive history of the birthplace of punk music, CBGB, has just been re-issued by Trouser Press Books, an all-music imprint headed by veteran music journalist Ira Robbins.

Originally published in 1988 and out of print for decades, This Ain’t No Disco: The Story of CBGB is a warts-and-all history of the legendary Bowery venue related by nearly 100 of the insiders who performed, worked and braved pre-gentrification Downtown NYC to witness the birth of punk music. Written long before the legend overtook the reality — while the club was still open and most of the principals alive — this is the real story told in gritty, outrageous and sometimes hilarious detail by onetime Billboard Magazine editor, the late Roman Kozak. The 2024 edition includes a new forward by Chris Frantz of Talking Heads, 12 pages of photos by Ebet Roberts, and a post-script by Ira Robbins that takes the story forward from 1988 to the October 2006 shuttering of the club.

Kozak’s book includes unguarded quotes from CBGB found Hilly Kristal, Joey and Dee Dee Ramone (the Ramones), Chris Stein and Clem Burke (Blondie), Richard Hell and Richard Lloyd (Television), Lenny Kaye (Patti Smith Group), Annie Golden (The Shirts), David Byrne (Talking Heads), Seymour Stein (Sire Records) and many more.

As a member of several of the more than 10,000 bands that performed at the club in its 33-year run, it was a treat to take a trip back … without having to once again experience the foul ambiance of its legendary and always-broken bathrooms!

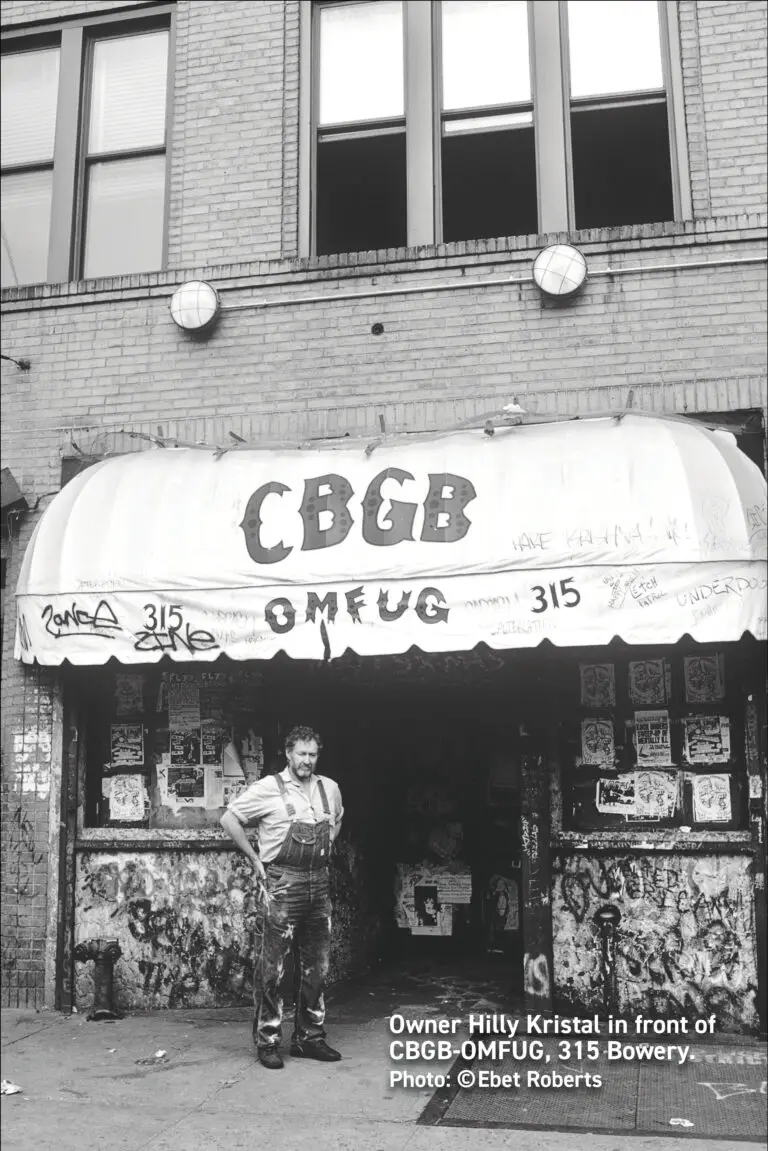

CBGB came about when its owner, Hilly Kristal, a wannabe singer, left his former bar in the West Village for the grimy Lower East Side to escape the noise complaints of his Greenwich Village neighbors. His short-lived attempt at a country music venue, one with sure to fail breakfast time gigs, would be shelved when Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd of Television lied their way into a performance in March 1974. Television’s stint would shortly attract other bands, including The Ramones, the first act signed to a major label, a quartet that could crank out 20-song sets in 17 minutes or less. By the end of the year, CBGB, which would initially feature other kinds of music along with comedians, would become an all-rock venue.

The first two years of CBGB would be hand-to-mouth, with Hilly living on a cot in the back of the club and supplementing his income by buying a truck and starting a moving business, one that employed his favorite starving musicians like the members of The Shirts. Various musicians and staffers humorously relate memories of dodging the many “care packages” left on the floor by Hilly’s dog, Jonathan, and the suspect quality of Hilly’s infamous chili and hamburgers. Mink Deville claims Jonathan was the source of the crabs he got four times in the seedy but beloved club. And there is much talk in the book about the decrepit bathrooms, for their sub-Third World sanitary conditions and where the truly brave might partake in the classic drug-and-sex combo. “You could always see four feet in the bathroom stall,” said Dick Manitoba.

The book contains interesting facts about the humble and initially stumbling beginnings of the early CB’s bands who would become legends, including Blondie and Talking Heads. Elda Stiletto and busy backup singers/present-day cosmetic company giants, Tish and Snooky, tell of Blondie’s early days, the gestation in Elda’s band, and false starts as Angel and Blondie and the Banzai Babies before settling on a firm lineup anchored by drummer Clem Burke. Another memorable night was when Talking Heads and The Shirts auditioned together. Hilly loved the first because they were “neat” and carried “very little equipment.” And though they didn’t reach the commercial heights of other early CBGB bands, The Shirts would prove Kristal’s favorite. He would go on to manage them, secure their three-album deal with Capital Records, and a role for their lead singer, the now busy actress Annie Golden, in Milos Foreman’s movie version of the Broadway musical Hair.

CBGB began to pick up steam with the arrival of Patti Smith, who had a four-day-a-week, seven-week residency in Spring 1975. Kristal compares the excitement to comic Lenny Bruce’s residency at the Village Vanguard when Hilly was helping manage the club for owner Max Gordon. The two-week CBGB Rock Festival in July 1975 wouldn’t bring in a huge amount of cash, but it generated tons of press from outlets like The Soho Weekly News, Village Voice, etc. Writer Legs McNeil, the man who popularized the term “punk” appropriated from a favorite term of TV’s Kojack, called CBGB “a juvenile delinquent hangout, where everyone was equal because they were broke.” To Richard Lloyd, it gained traction because “it was a reaction to hippie stadium music.” By 1976, the club started making money, and one of the essential ingredients of success began to happen: the girls started coming in droves, according to Tish and Snooky. In July 1976, CBGB invested in a new sound system, which would be ripped off then replaced, making it the best-sounding live room in New York City and maybe the world. It became a venue that would attract artists from around the globe, including the then-unsigned Police, who played for an audience of 10 in July 1977.

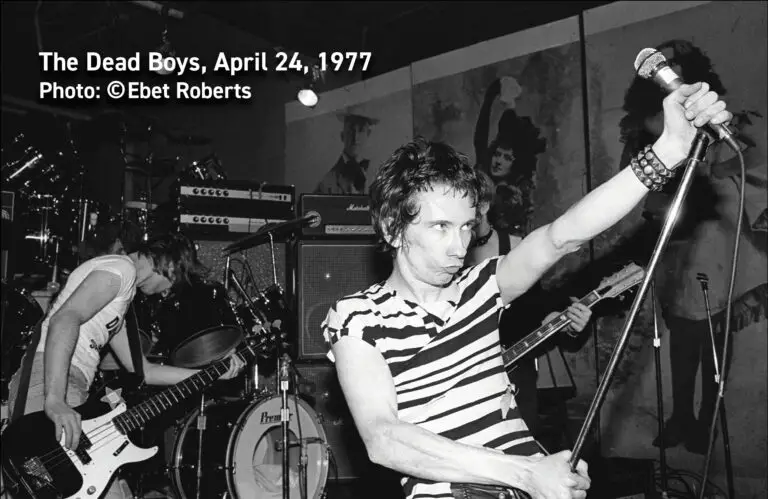

There is lots of good dish on Hilly’s failed ventures, like his short-lived CBGB Theater on Second Avenue, the proposed punk rock sitcom, TVCBGB and his ill-fated management of another popular attraction, The Dead Boys. The book also relates how CBGB’s slow burn rep as the birthplace of punk was usurped a bit by the UK – the rapid rise of the Sex Pistol and the appropriation of the spiked hair and torn t-shirt originated by Richard Hell. When the club launched it was the only game in town for bands playing original music, a refuge where virtually anyone could get a shot at their Monday audition nights. But by the 1980s, CBGB would have competition from new clubs like Hurrah, The Ritz, Danceteria, The Peppermint Lounge, the Mudd Club and more. But most would not survive the decade.

But even with all this buzz, CBGB-style punk was “poison as far as record companies were concerned.” Except for Blondie, whose breakthrough came from a disco infusion in their #1 singer “Heart of Glass,” CBGB bands didn’t move platinum units of vinyl or CDs or get much radio airplay. Bands like latter-day favorites, the chainsaw-wielding, car-blowing-up Wendy Williams and her Plasmatics, had to make their living on the road.

In the mid- and late-1980s, CBGB would birth another musical genre – hardcore. It’s Sunday hardcore matinees did big business at the door but not much at the bar, as many devotees were underage or straight arrows who didn’t drink beer. One CBGB barkeep recalls: “We could make $2,000 at the door and only $200 at the bar.” Bands like Murphy’s Law, Agnostic Front, Cro-Mags, Bad Brains, The Beastie Boys, and Damage were featured; some also on cassette-only releases of live performances on a CBGB imprint created with Celluloid Records. Many of these and other new artists would have their albums featured at a new satellite, CBGB’s Record Canteen.

Kozak wraps up his history in 1988, well before the legend was glammed up via the 2013 feature film and the ridiculously “reopened CBGB” restaurant at Newark Airport. Trouser Press’s Ira Robbins provides a coda detailing Hilly’s losing battle with his landlord and the August 2006 benefit concert that attempted to save the club. (Note: this reporter did PR for that event pro-bono during his agency days. He also had his electric mandolin stolen at the club! The first gig by my long-running project, Spaghetti Eastern Music, took place at CBGB Gallery in 2003).

Kozak’s tale concludes with one of many significant observations in the book from guitarist/writer/record producer Lenny Kaye, a thought posited on the Lower East Side’s new monied residents.

“The key and glory of CBGB is that they’ve never gotten too big for their britches. They’ve never gone above their own Bowery station…even though the Bowery is above its own station now.”

Order This Ain’t No Disco: The Story of CBGB here.

Comments are closed.