The Hudson Valley’s Catskill Mountains are known as the powerhouse of folk music. The land’s rich history is a testament to its iconic music scene. No matter where you wander through the Catskills, you’ll pick up the musical culture that these small communities have. But what brought folk music to the Catskills in the first place?

To start, the history of colonial Catskills is right there in the name. Dutch settlers in the 1600s brought many of their traditions and their language to the Catskills. The old Dutch word “kill” translates to river or stream in English. The word “kaats” translates to cat, referring to the bobcats and mountain lions. So the region was coined “Kaatskill,” later anglicized to Catskill.

In pre-colonial times the Catskills was made up of the Mohican, Munsee and Lenape nations, that is until Henry Hudson sailed up the river now named after him in 1609. Robert Juet, one of Hudson’s crew members, was said to be the first European to take note of the Catskills specifically.

In 1667 the Anglo-Dutch War ended with the Breda Treaty in which England received “New Netherlands.” In the decades to come, more English settlers moved to the land, but the Catskills never lost its Dutch Heritage. Sojourner Truth, who was born over a century later, grew up in a Dutch Plantation in Ulster County. Although she spoke English, she never lost her Dutch accent.

As more European settlers moved to the Catskills, different ethnic towns like Germantown, located east of the river, began to pop up.

Although New York had long been colonized, it was still too unexplored throughout the 19th century to be substantially populated. The Catskills were partially desolate but it was the land itself that maintained a community of people in the area. Fur trade and beaver trapping were both profitable trades. The abundance of hemlock bark in the areas allowed tanneries to flourish. Needless to say, these industries brought more and more families to the Catskills.

New York City began to become dependent on the Catskills. Reservoirs in the land have been providing water to the city’s residents since 1916.

As water was flowing from the Catskill reservoirs, the region pulled in more and more city residents. In 1906 the Arts Students League of New York City opened a summer school in Woodstock. This was the beginning of the arts and music town that we know today.

The League brought in mostly visual artists, around 200 students a year from 1906-1922 and again from 1947-1979. They were said to continue their individualistic lives, enjoying their solitude outside of the city.

Perhaps the most famous artist that moved to Woodstock was Bob Dylan. Dylan moved to the small town in 1965 after visiting with his then girlfriend Joan Baez. It was above Cafe Espresso on Tinker Street that he wrote Another Side of Bob Dylan and Bringing It All Back Home.

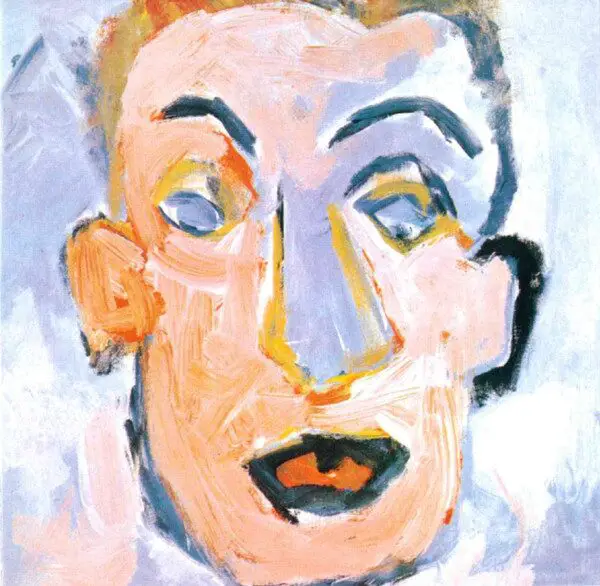

After a motorcycle accident, he continued his private life in Woodstock and turned to a new artistic outlet- painting. In 1970 he painted his album cover for Self Portrait. He also started working with a group of musicians called The Hawks, now known as The Band. They collaborated on Dylan’s album The Basement Tapes and The Band’s album Music From Big Pink. Dylan also created the Big Pink album art. The Band’s Levon Helm went on to make a lasting creation in Woodstock with Levon Helm Studios.

It wasn’t only artists that flocked to the Catskills. The year-round scenery drew tourists from all over New York to high end resorts and hotels. Perhaps the most significant hotel in Catskill history was The Catskill Mountain House located in Palenville. This almost mythical house opened in 1824 and was visited by presidents U.S Grant, Chester A. Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt. The Catskills began to be overshadowed by a more Upstate park, The Adirondacks, and the mountain house had its last season in 1941. It was demolished in 1963 despite the passions of preservationists.

The modern equivalent to the Catskill Mountain House may be the Mohonk Mountain House, a resort and spa located overlooking a glacial lake. The Victorian style castle was built in 1869 and brings in guests from all over the world. The house sits on top of 40,000 acres of protected land thanks to conservationist efforts of the past.

In 1904 the state gained ownership of 92,708 acres of land officially making The Catskills a protected State Park.

Catskill tourism began to bring in families specifically of Jewish faith. This became known as the Borscht Belt, referring to the Eastern European soup. In the Borscht Belt heyday during the ’50s and ’60s, more than 1000 Jewish resorts were scattered the Hudson Valley. Today, the Borscht Belt Museum in Ellenville is dedicated to the rich Jewish history in the Hudson Valley.

With its forests, mountains and streams, the Catskills were the perfect terrains for summer camps, one of which was Camp Woodland. Woodland was founded in 1940 by Norman Studer who was an educator at the Elizabeth Irwin School in New York City. Studer’s purpose with Woodland was to give children a destination full of diverse folk culture.

Michael Pastor, who was a Woodland camper from New York City, remembers what it was like to be a part of this famous camp in folk history. Pastor says the eight weeks of camp he attended annually from 1958 to its last year in 1962 consisted of classic camp activities like football, games, outdoor excursions and of course music.

“A lot of campers played guitars, and so there was an awful lot of music going on all the time. I started playing guitar when I was 12 at camp,” He said. “It was kind of hard to hear yourself anyway, because there were 30 other guitars playing and a few banjo players as well.”

In a time of McCarthyism in America, Woodland was called “Camp Red” by conservatives referring to its teachings of inclusion and community building. According to Pastor, there was never any outright democratic or communist values being preached, but many of the families that sent their children to Woodland were leftward leaning.

Pastor remembers the diverse music the campers performed. “Some of the music were Union songs from the 1930s. Also, there was a variety of international flavor to the music. We would learn songs from different languages,” he said.

Studor was always reaching out to the local community to teach kids about the history of the area. Pastor says he remembers community members including a local historian coming in to tell stories of the tanneries and music of the past.

Woodland also attracted legendary artists like Ella Jenkins and Pete Seeger. Seeger performed every year for all age groups, inspiring the whole camp.

Pastor says that being around music all summer and seeing artists like Seeger sharing their talents ignited a passion for music for campers. “A person who I met during my very first summer camp, my very first day of camp, Peter Simon, he and I are still very close friends and he, inspired by Pete Seeger, became a banjo player. We had a bluegrass band when we were in high school and we still get together regularly and play sort of old time traditional countries,” Pastor noted.

Seeger was born in New York City and raised in Dutchess County. He was first inspired to pick up the banjo when he traveled to Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s folk festival in Asheville, North Carolina at the age of 16. In 1938, he settled in New York City with other folk musicians known as The Almanac Singers in “The Almanac House.”

In 1949 he began to perform with a group known as The Weavers. A year later, the anti-communist book Red Channels came out which accused Seeger of being a communist. He became a blacklisted musician and the accusation loomed over Seeger’s head for decades.

According to his daughter he was never a self proclaimed communist. “He believed in community and he believed in it, whether it was a family, a school, a town, a country, the earth, but he wasn’t a communist. He was more like a ‘communityist,’” said one of his daughters Tinya Seeger. “He wanted good people who could do good things in office. That would be where his politics lay.”

She said that although he was never a communist himself, he was curious about life under communism. He visited North Vietnam during the Vietnam war along with communist China and Soviet Russia multiple times.

In 1955 he was called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee and was questioned about his political beliefs. He refused to answer their questions leading to 10 counts of contempt in 1956 followed by an indictment two years later.

During his blacklisted period, Seeger still created new music and performed all over the country. Some critics believe it was in these years that his best work transpired. He played gigs in smaller venues and college campuses, communities where folk itself began. His children’s albums were a huge success in summer schools and camps like Woodland.

At multiple performances, conservative community members would protest outside the venue but it never stopped him from performing. “He was happy when he saw free speech. He really believed very much in a person’s right to express how they feel, that you should be able to do that and life goes on,” remarked Seeger.

No two Pete Seeger shows were one in the same. He based his performance on the people that were in the audience. If there were children, he would play children’s songs like “Abiyoyo” or “The Foolish Frog.” If the audience was mostly older adults he would play songs to remind them of their childhood like “If I Had A Hammer.” His set list wouldn’t be determined until he was on stage.

At some of his concerts, audience members could leave him notes on the stage before the performance started. He made sure to read every one of them.

Seeger narrowly escaped prison time in 1962 when a Court of Appeals decided his 1961 conviction was faulty and deserted the case. Already infamous within right leaning circles, he became heavily involved in the civil rights movement and antiwar movement during the Vietnam War.

He was also active in local initiatives as well. His home in Beacon was located along the polluted Hudson River and he was determined to help this ecosystem. Seeger, along with some of his friends in the community, built a sloop named Clearwater, modeling the same boats that sailed the Hudson in the 18th and 19th centuries.

He sailed up and down the river educating listeners about the problem and collecting donations in his banjo case. His efforts actually cleared the river and although the river isn’t completely absent of garbage and pollutants, Hudson Valley residents today enjoy a much cleaner river than those in the 1960s “In those last 10 years of his life, he was trying to say things that were meaningful,” Seeger said.

Seeger understood the relationship between the art of folk music and community. According to his daughter, he liked living in Beacon with his family and a generation of adults that were raised on his music. “He created something that was like a camp experience within the Hudson Valley. Maybe it’s just that the same people were coming to the smaller gatherings that were happening around,” Seeger notes. “I think they were carrying on the tradition.”

Pastor, who is one of those campers carrying on the tradition, says he feels a strong community surrounding folk. “There is a bond that people feel throughout all these decades and I think if you were to ask people, you would find that music is a part of that shared experience, that’s part of that bond. Music was so interwoven with camp life, it’s kind of hard to describe,” he said.

Seeger is survived by his family including Tinya Seeger who lives in the Seeger home in Beacon, New York.

A decade after Seeger’s death, the tradition of Catskill folk continues. The music that was birthed from the land is dependent on the story of the Catskills. Folk was a distraction from work, a time of recreation and bonding for rural families. It was an expression of self for the collection of artists that gathered in the region.

Another family that carries on the trend of intergenerational folk is the Helm Family. The Arkansas native Levon Helm of The Band settled in Woodstock in 1967. In 1975, he built Levon Helm Studios, putting down permanent roots in Woodstock. His family, including his daughter Amy Helm, continue his legacy with “The Helm Family Midnight Ramble,” an annual celebration of his art at Levon Helm Studios.

Today, the studio showcases independent artists and bands from all over the country.

Helm recorded the Dirt Farmer album in his studio which won a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album in 2008. Guitarist Larry Campbell, who also worked with Dylan, produced the album alongside Amy Helm. They both sang and performed on the album as well.

Dirt Farmer is not only an award-winning album, but it was deeply personal for Helm. It was his comeback album, his first since 1982. He started recording as he was battling throat cancer, despite the damage to his vocals.

The acoustic tracks are a nod to his Arkansas roots, but they have a clear Catskill influence. Each song tells a story of the human condition. “Anna Lee” is about children who remember their late mother by her lullabies. “Wide River To Cross” is the final track on the album. In it Levon describes his journey of life, being “only halfway home.”

Amy Helm, who has recorded solo music at the studio, was born in Woodstock and grew up watching her father perform. With her three folk albums, she continues to carry on her family’s legacy and tour around the country.

The Catskills and its history have shaped perhaps hundreds of solo folk musicians as well as contemporary bands.

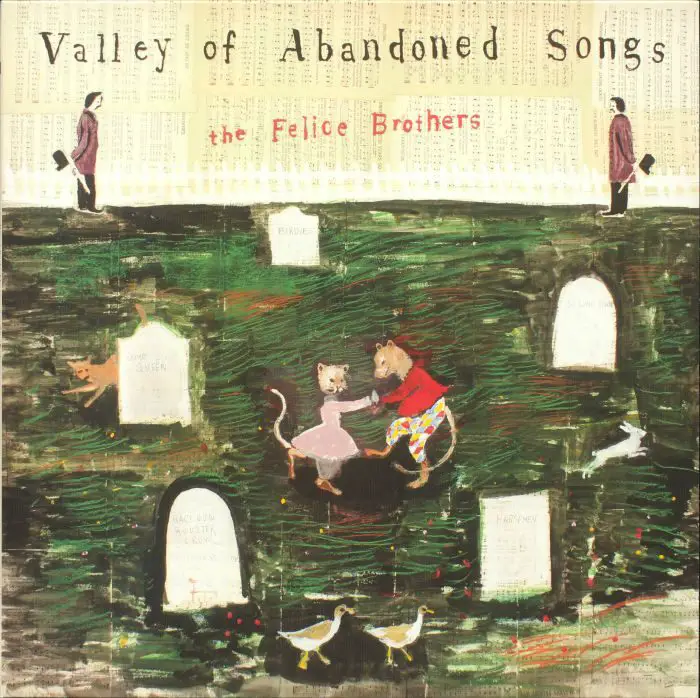

The Felice Brothers, originally from Palenville in the Catskills, are one of the most popular folk groups today. They’ve released ten albums including their latest 2024 album Valley of Abandoned Songs. Ian Felice (guitar/vocals), James Felice (piano/vocals), Jeske Hume (bass), and Will Lawrence (drums) bring back the raw, acoustic sound of the region.

In a recent interview with NYS Music, James Felice stated that the category of Folk and Americana felt limiting to the band early in its takeoff, but later, he embraced the labels. “All of our music, the way we play and the music we grew up with is folk music. It’s the music that we are most connected to. So yeah, I’m okay with that. I think we’ve been doing this long enough to have our sort of thing,” he said.

Hudson Valley artist Mikaela Davis moved from Rochester, after her first album, Delivery. Davis got her degree in harp performance at the Crane School of Music in Potsdam. The harp, an unusual instrument in the genre of folk, compliments her whimsical vocals and takes the instrumentation to a new level. She produces a blend of indie-pop and Catskill folk inspired by sounds from the ’60s, the golden era of music in this region.

Davis records and performs with her own musical family. She has known her drummer Alex Coté since childhood, guitarist Cian McCarthy and bassist Shane McCarthy from college and she met steel guitarist Kurt Johnson in her early twenties.

The Bones of J.R Jones, another artist from Central New York, started his musical career playing in hardcore punk bands until he became more interested in American blues and folk musicians of the 1930s and ’40s. He officially launched his musical project, The Bones of J.R Jones, in 2012 as an independent artist.

Although his music is categorized as folk, indie and punk, he doesn’t write with genre in mind. “I honestly believe the music we create is a reflection of life experiences,” he said. Since his start, he has released five albums. In 2021, he relocated from Brooklyn to a Catskill farmhouse.

He says, in his experience, the Catskills have been a welcoming environment for him and the music community is supportive and uplifting. There is also something very special about the slow sleepy hills and mountains here. “We are just out of the reach of the weekend crowd from NYC so in a way, it stays true to itself. It’s a magical place full of inspiration,” he notes.

Upstate, with Brooklyn connections, settled in The Hudson Valley and over the past 11 years of performing together, have released three bold harmonious albums.

Members Mary Webster, Melanie Glenn, Harry D’Agostino and Dylan McKinstry recorded their most recent album, You Only Got A Few, in the Hudson Valley at The Building in Marlboro, New York and Greenpoint Recording Collective in Brooklyn, another musical hotspot for independent music.

Laura Zarougian is a solo artist who describes herself as an “Armenian Cowgirl,” inspired by American folk as well as her Armenian roots. She is a multi-instrumentalist and a powerful vocalist. Her songs tell stories of her family lineage and explore themes of searching for home. “Cairo,” from her 2023 album Nayri, tells the story of her great grandfather’s death and her grandmother’s journey to bring his body back to Cairo.

Zarougian grew up in Boston, but her musical career blossomed in Brooklyn. She now lives in Red Hook, a town right next to the Hudson River. “I do feel like there is a really strong sense of community here in which people want to support local musicians and do their best to promote them,” she said. Nayri is a seven-track album recorded with her partner, drummer Mike Alan Hams. The storytelling in her music captures the spirit of Catskill folk. “It’s definitely got some twang and elements of Americana and folk. But a lot of my songs, especially on my first album, had to do with my Armenian American identity,” she remarked. “I think folk songs have to do with place and longing and all of these things that are just part of the human experience.”

The folks that are keeping folk alive are the “grassroots” groups and families that create music without the pressure commercial industry influences.

Just days before his passing in 2014, Seeger attended the annual celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr., in Beacon.

“What did my father do? You know, sometimes I say he was a singer and entertainer, but he was somebody that was really trying to help people get along,” Seeger said. “His version of helping them communicate was to write music.”

Seeger is still one of the most well-known folk singers in America and his work in activism and the folk revival movement live on.

Comments are closed.