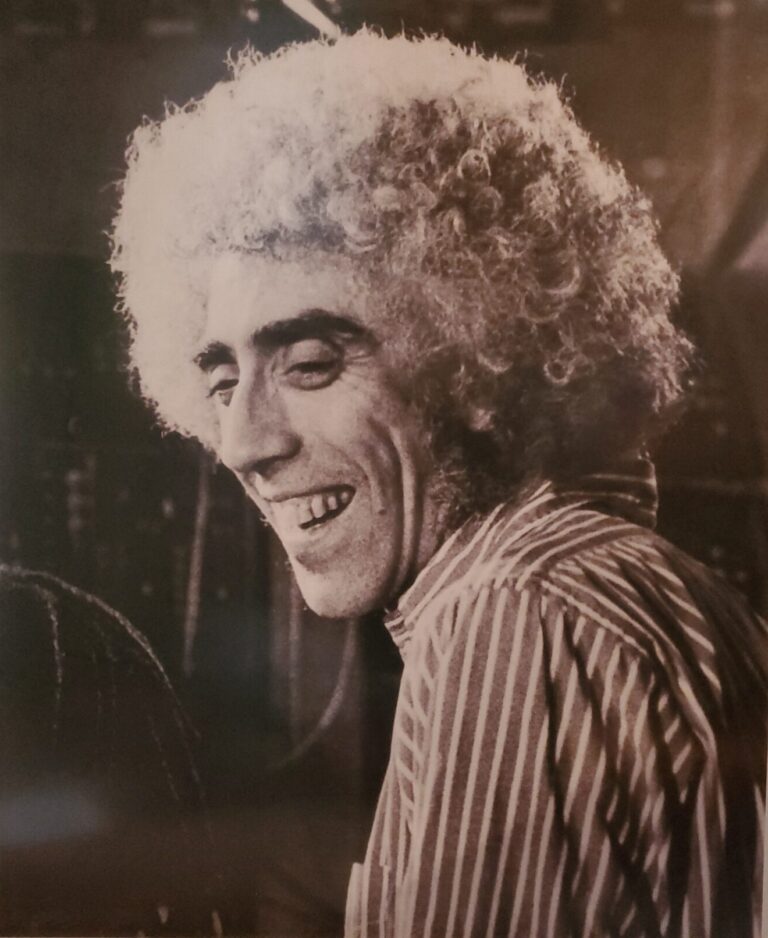

On March 28, the music world, and the Hudson Valley’s close knit community of music makers, lost another great one, Malcolm Cecil. The much-traveled musician, producer and Grammy-winning engineer passed away after a long illness in Malden-on-Hudson, where he had lived and continued his work for the past two decades.

Though Cecil was a man of many hats he is perhaps best known as the co-creator of TONTO, the world’s largest analog synthesizer. This room-sized amalgamation of a variety of synths and sound processors would become the musical bedrock for the dozens of albums he helped produce. Most notable are Stevie Wonder’s revered quartet of classics from the 70s, Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions and Fulfillingness’ First Finale.

Born 84 years ago in London, Cecil seemed predestined for a career in music. According to a 2007 profile by Peter Aaron in Chronogram, Cecil’s American grandfather was a movie organist in Times Square theaters, while his mother played violin, piano and accordion in a gypsy band that his father managed. After an aborted attempt at piano, Cecil switched over to bass and ultimately became a much in-demand player.

Cecil would go on to stints in the BBC Orchestra and the house band at Ronnie Scott’s, London’s leading jazz club, where he performed behind luminaries like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Stan Getz and Herbie Mann. Cecil also co-founded Blues Incorporated with Alexis Korner, the ensemble where the young Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts and other rock stars-to-be got their first taste of stage experience.

A ham radio enthusiast in his youth, Malcolm’s acumen in electronics grew when he served as a radio technician in the Royal Airforce. While stationed in Newcastle, he got together with The Animals and Hendrix’s manager-to-be, Michael Jeffries, and opened a jazz club called The Downbeat, which he wisely outfitted with recording gear. Seeking to get a contract for The Animals, Jeffries asked Cecil if he could demo a rehearsal by the rockers in the club’s off-hours, which he did on his trusty Revox according to TapeOp. This demo contained the proto-version of “House of the Rising Sun” which earned them their record deal, a #1 hit and global fame.

After a detour to South Africa, Cecil ended up in the U.S. in the late 60s. The bassist toured with several jazz artists before taking a job maintaining equipment at Mediasound, a busy Manhattan recording studio where he would meet his partner in technology and music production, Bob Margouleff.

Margouleff had bought one of the early Moog series IIIc synthesizers and teamed up with the more technically adept Cecil to expand upon it, combining a variety synths from Moog and ARP with an array of custom modules, processors and controllers from a Russian composer and Jimi Hendrix’s guitar tech.

In the end, it was a six-foot tall, 300-square foot sound-making monster, one which the duo used to conjure a galaxy of spacey and downright funky sonics. They cheekily dubbed it TONTO, for The Original New Timbral Orchestra. And after a chance meeting with his old acquaintance Herbie Mann, Cecil scored a record deal with the flautist’s Embryo label. In 1971, they released their hugely influential debut album, Zero Time, as the equally cheekily named Tonto’s Expanding Headband.

Zero Time was a revelation to music makers, and none more so than Stevie Wonder. One day Wonder turned up at Mediasound (in a pistachio colored jumpsuit) with a copy of the album under his arm seeking a demonstration. After a quick tour of TONTO, he immediately booked a session with the duo. Over the course of a single weekend, they produced a remarkable 17 songs. Wonder then had TONTO moved to Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios and the trio would collaborate there over the next four years on soulful innovations that would remake the sound of popular music. Together, they co-produced the classic quartet of Wonder’s best loved albums, containing songs like “Superstition,” “Higher Ground,” “Living for the City,” “You and I” and many more. Cecil not only helped Wonder dial up the sounds heard in his imagination, but often performed them on the discs.

In 1975, Malcolm Cecil and Margouleff would split, with Cecil purchasing TONTO outright and continuing its expansion, as both an instrument and a sonic spice dusted onto rock, R&B, jazz and experimental idioms.

Cecil would go on to produce and provide his engineering expertise to a stunning number of acts in the following three decades. These included The Isley Brothers, Steven Stills, Weather Report, Minnie Riperton, Randy Newman, James Taylor, Jeff Beck, The Jackson Five, Little Feat, Steve Hillage, Dave Mason, The Doobie Brothers, Mandrill, Quincy Jones, Bobby Womack, Joan Baez and more.

One of Cecil’s longest lasting collaborations was with soul poet/proto-rapper Gil Scott-Heron. Cecil produced several of Scott-Heron’s acclaimed albums beginning with 1980 in its title year, which featured Gil and his musical partner Brian Jackson in the studio with TONTO on its front and back covers, through to 1994’s Spirits.

TONTO came with Cecil when he moved to the Hudson Valley, with a couple of notable detours. These included a stay at Devo founder Mark Mothersbaugh’s Mutato Studios, where he used TONTO to create the music for the Rugrats animated series in the mid-1990s. Aaron’s article includes an interesting description of TONTO’s humble home in Cecil’s backyard shed in quiet Malden. In order to preserve this one of a kind piece of musical history, Cecil sold TONTO to The National Music Centre in Calgary, Canada in 2013. The museum completed a full restoration in 2018 and today offers it for music production services.

With his move to the Hudson Valley, Cecil continued his recording work with TONTO, creating the lush New Age-y sounds on his album Radiance, and in other partnerships, including one with Russian violinist Valeri Glava as Superstrings. Cecil also returned to his first musical love, acoustic bass, playing regular jazz gigs at cozy Hudson Valley clubs like the Colony Woodstock.

I first met Malcolm Cecil at such a gig. This was in October 2019, when we were both playing our respective sets on the sidewalk as a part of the outdoor ShoutOut Saugerties Music Day. The woman who organized this community attraction was Cecil’s neighbor, Isabel Soffer. She is an internationally known curator and live event producer, co-founder and director of globalFEST, the pre-eminent annual showcase for World Music in the U.S. She had been working for the past two years with Malcolm on various projects.

As is all too often the case in the music business, Cecil did not acquire or continue to receive great wealth from his tireless creative efforts. According to several sources, Cecil was not a participant in royalties from some of his best known works.

In mid-November 2020, Soffer called me to see if I might volunteer my day job skills, as a publicist, to help her and Malcolm get some new projects off the ground. Naturally, I jumped at the chance to meet and talk with a musician I had revered since I was 13 years of age, when I first heard Zero Time on WNEW-FM in NYC.

As with TONTO, part of his desire was to preserve and have others benefit from his legacy. Malcolm Cecil maintained a huge archive of recordings, correspondence, photographs, videos, recording equipment, session notes and other artifacts from his six decades in music, ones that are important artifacts from some of the most vital chapters of 20th Century music. As he got on in years, he was hoping to find a proper home for this massive archive.

Also on his mind was a possible 50th Anniversary release of a Zero Time/Tonto’s Expanding Headband boxed set, with unreleased tracks and other goodies. There was also discussion of tribute album featuring notable musicians and helmed by a star producer.

Malcolm was also taking steps to prepare a biography, a unique one to be told in the voice of TONTO. It would be machine telling of his adventures in sound and in-studio with many of the most talented names in music. Another neighbor, a Vanity Fair writer, was urging Malcolm to tell his tales in the form of a podcast they would co-produce.

Cecil was also well on the way to finalizing a series of projects around two giants, Muhammed Ali and Gil Scott-Heron, ones that might still come to fruition with the proper support. He was planning to combine the music from his Radiance album with spoken word from a lecture by Ali for an album to be released in June 3, 2021, the 15th Anniversary of the champion’s death. With Gil, there were three discreet projects in the works, a re-release of The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron, a piece he wrote on the day John Lennon died called “Third Person,” and a music/poetry project with Scott-Heron’s daughter Gia.

As 2022 would be the 50th Anniversary of the release of the first of his Stevie Wonder collaboration, Music of My Mind, Malcolm Cecil was looking forward to celebrating the landmark with his own new music inspired by the event.

Two short weeks after I spent a few hours with Malcolm hearing his plans and remarkable stories, I heard he was hospitalized. Our work stopped for the moment, in hopes that Malcolm might rally and continue his work.

But even with his passing, Soffer is encouraged. She is hoping the many who loved and admired Malcolm Cecil and his work will come together to bring some of these final projects to life.

Sal Cataldi is a publicist and musician living in New York City and the Hudson Valley. He is President of Cataldi PR and leader of the band Spaghetti Eastern Music and member of the duos Guitars A Go Go and Vapor Vespers.

Comments are closed.