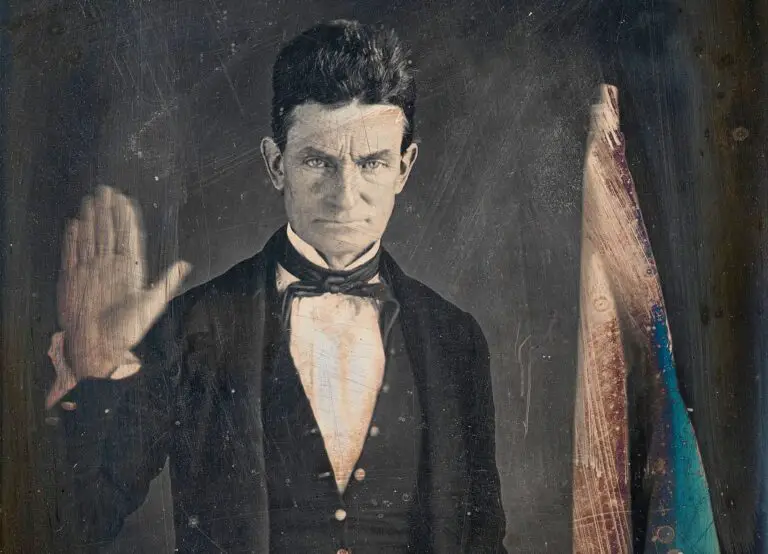

Amid the political turmoil that we have seen unfold in 2025, the abolitionist John Brown has been popping up in the social feeds of the left. The phrase “Don’t argue with people John Brown would have shot” jumps out as a bold statement, and insists on a knowledge of this particular figure in American history.

A true patriot who fought to end the institution of slavery and for equality of African-Americans, John Brown was a man who swore an “eternal war with slavery,” and gave his life for that cause, thus deserving of accolades for his actions to protect the freedom of all Americans.

But even a brief dive into the life and death of John Brown will bring you to the song “John Brown’s Body.”

In researching this song, I couldn’t get into the history without reaching out to Ithaca reggae band John Brown’s Body, who have been performing for 30 years now, and are celebrating their anniversary in Boston on December 5. The band shares more than just a name with the song; they share the spirit of John Brown through their music, something indicative of the roots of reggae music in Jamaica.

When Kevin Kinsella, founder of John Brown’s Body (and later 10 Ft. Ganja Plant), was tasked with coming up with a name for the band in 1995, he thought of the characteristics of roots reggae from the late 60s and early 70s. Jamaican bands and artists such as Bob Marley, Burning Spear, Toots Hibbert and Mighty Diamonds would sing songs in celebration of fallen activists and freedom fighters, among them, Marcus Garvey and Nelson Mandela.

Kinsella noted, “One thing I liked about roots reggae of the time was the inclusion of history, and being a history buff myself, I thought about a band that celebrated someone like that from the United States. I looked into our country’s history, and John Brown is a great example of someone who fought for rights and justice and the struggle for emancipation. Those are the real parts of what reggae music is about, fighting for the oppressed, for liberation.” The band, named after the man himself, the freedom fighter who gave his life to the cause of abolishing slavery, is fitting for the band, especially now, living in a polarized time, akin to the time of John Brown, where protest, and protest music, both take on deeper meaning and offer increased connection to the past.

One song of protest that became a staple in more ways that one, was “John Brown’s Body,” where a simple version of the Union troop anthem was sung as they marched to battle, “burned a stripe across Georgia” or simply taunted Confederates while marching into defeated towns. The effect of celebrating the man whose death ignited the Civil War, in front of those who sided with his executioners, surely left lasting scars for those on the losing side.

“John Brown’s Body,” originally “John Brown’s Song,” centers around our protagonist, the abolitionist John Brown, who lived the last 11 years of his life in North Elba, NY. Even though he was not always present on the farm, his family and children lived there, now a National Historic Landmark worth visiting on the way to Lake Placid.

The death of John Brown was the original spark for the Civil War – almost a full year before Abraham Lincoln was elected president and South Carolina seceded from the United States – having been hanged on December 2, 1859, for a failed raid on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, on charges of treason, murder and insurrection. Thus, the legend of John Brown was carried by Union troops, eventually developing a song in the tradition of folk hymns in the American camp meeting movement, a product of the Third Great Awakening.

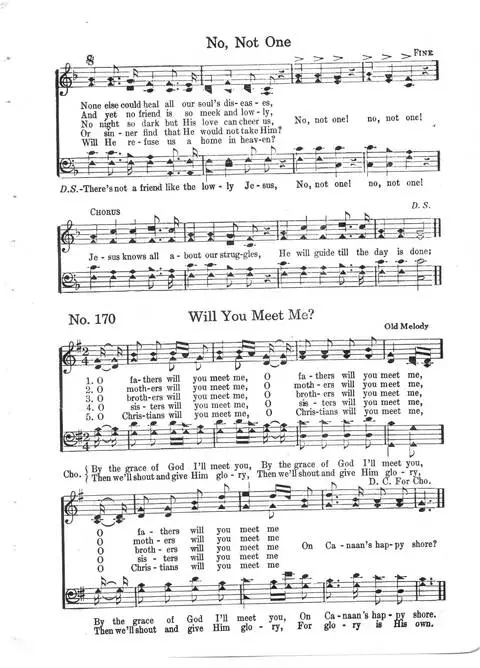

During this period of American history, particularly in what would now be considered ‘rural’ areas, these frontier regions would have regular church service gatherings, since churches were not always readily accessible in the sparsely populated areas. Going beyond the religious purpose, just as today, socializing was a major component of camp meetings, with songs taught and passed down and around to attendees. These folk songs, and sometimes just the melodies, would change over time, adopting slightly different rhythms and having distinct lyrics applied.

Among the songs that can be traced to these camp meetings is “Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us”, the melody and original verses written by William Steffe around 1856.

Say brothers, will you meet us?

Say brothers, will you meet us?

Say brothers, will you meet us?

On Canaan’s happy shore?

Glory, glory hallelujah!

Glory, glory hallelujah!

Glory, glory hallelujah!

For ever, evermore!

Traced back to Charleston, SC, the song was sung at Methodist camp meetings and the churches of free blacks, later evolving into what we know as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Eventually, verses related to John Brown were substituted, and Union soldiers came up with new lyrics referring to both the martyr John Brown, but also a Sergeant John Brown among the troops that inspired banter and comparison of the legend and the soldier. The popularity of John Brown – his actions, methods, trial and execution – made him a martyr to many Abolitionists and African-Americans, as well as those in the North fighting to preserve the Union.

Confederate soldiers played a role in the song’s popularity as well – adding in their own lyric “John Brown’s a-hanging on a sour apple tree” – which only instigated the Union soldiers to modify that lyric to “They will hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree,” with one regiment – the Massachusetts Twelfth – credited with spreading the song’s fame in their marches.

Thus, as soldiers carried the song’s revised lyrics and the melody was well known, it would only take one more step before “John Brown’s Body” would become “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” That occurred in November 1861, when Julia Ward Howe (the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters) and her husband – both abolitionists – witnessed a skirmish between Union and Confederate troops, likely at Fairfax Court House, with soldiers led by Lt. Col. Edward B. Fowler (84th NY Infantry) vs. Lt. Col. Fitz Hugh Lee (1st VA Cavalry). Union troops who entered the fray singing “John Brown’s Body,” and hearing this, Howe was inspired to write a poem that evening, which would later be published in Atlantic Monthly in 1862. The opening line to the poem, “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord” would become better known as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

In March of 2025, writer Chris Ladd, spoke of the need to not only fight back against the authoritarianism of the current administration in Washington D.C., but to face the powers that be with stronger methods than the current feebleness of opposition leaders. In his article “Waiting for John Brown,” Ladd notes that even though Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry was a tactical failure, in the long term, it was a monumental strategic success, a prelude of what was to come in the full Civil War. Seeing a parallel between the pre-Civil War era and the political unrest of 2025, Ladd recalls the song that inspired millions of Union soldiers and citizens north of the Mason-Dixon line: “We remember that song as The Battle Hymn of the Republic while we try to forget Brown. We need to remember John Brown. We need to summon John Brown.”

“John Brown’s Body” Lyrics – William Weston Patton version, 1861

Old John Brown’s body lies a moldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But though he sleeps his life was lost while struggling for the slave,

His soul is marching on.

Glory Hallelujah!

John Brown was a hero, undaunted, true and brave,

And Kansas knew his valor when he fought her rights to save;

And now, though the grass grows green above his grave,

His soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

He captured Harper’s Ferry, with his nineteen men so few,

And frightened “Old Virginny” till she trembled through and through

They hung him for a traitor, themselves a traitor crew,

But his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see—

Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be,

And soon throughout the Sunny South the slaves shall all be free,

For his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

The conflict that he heralded he looks from heaven to view,

On the army of the Union with its flag red, white and blue.

And heaven shall ring with anthems o’er the deed they mean to do,

For his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

Ye soldiers of Freedom, then strike, while strike ye may,

The death blow of oppression in a better time and way,

For the dawn of old John Brown has brightened into day,

And his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

Comments are closed.