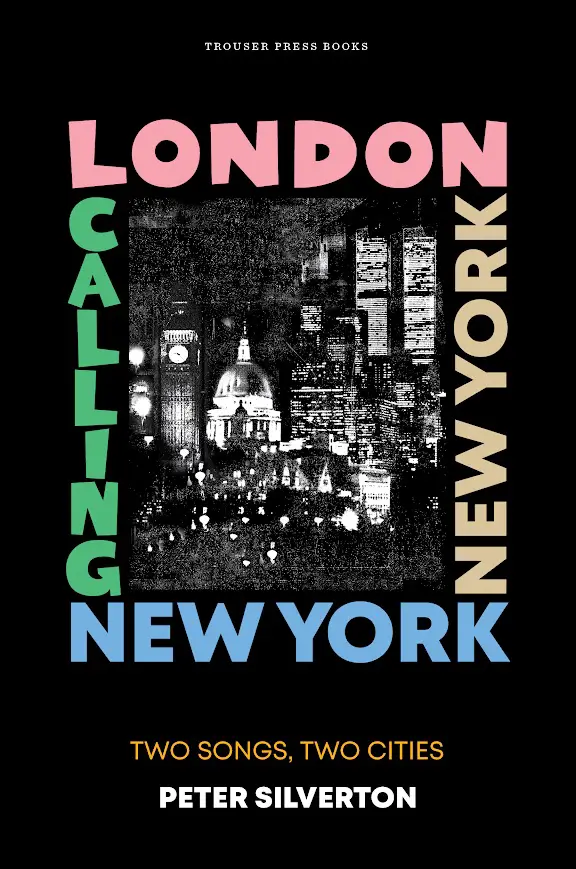

Trouser Press books, a New York-based publishing house specializing in music journalism and fiction, is publishing London Calling New York New York by English journalist Peter Silverton on March 12.

The book tells the winding tale – or tales – of the people and politics behind “London Calling” by the Clash and “(Theme From) New York, New York” by Frank Sinatra. By connecting these two iconic songs in unexpected ways, it reveals surprising and novel connections between two iconic cities.

London Calling New York New York is about “two popular songs from two different cultures… [addressing] nostalgia, mythmaking, family, crime, war, art, terrorism, politics, film, fidelity and propaganda.”

The book is being published posthumously: Silverton, who was a music journalist who knew Joe Strummer, lead singer of the Clash, and spent time covering Manhattan’s music scene in the 1970s and ‘80s, died of cancer in 2023.

The launchpad of London Calling New York New York (henceforth referred to, for my sanity, as LCNYNY) is the fact that the two songs – the one a forward-looking rage against the dystopian machine, the other a rose-tinted hark back to the excess and glamor of ‘50s New York City – were recorded within months of each other in the summer of 1979.

In theory, as a Londoner living in New York, I am well-placed to review this book. Reality is a little messier: I have had little exposure to the punk/post-punk music of the ‘70s, and hold a general suspicion, native to the English constitution, towards anyone who takes themselves too seriously. I have, therefore, left Sinatra’s discography largely untouched.

It is incredibly well-researched, and Silverton spares no expense in veering off the main thread to provide entertaining context. In one such diversion, he ties together a sea shanty, the Lower East Side club CBGB’s and a Scorsese film (more on him later) also set in New York City (Gangs of New York). The book is littered with these narrative figures of eight, woven with Nolan-like verve.

It can be a bit much. Frankly, I don’t need to know the filmography of the actor that the author’s adopted (gasp) mother’s stepfather (heave) looked like. It can feel at times like standing in an electronics store and looking at a dozen ultra-high definition televisions all showing different things – where to look?! it’s all so bright!

In general though, this trivia is wonderfully entertaining. Take his anecdote on the making of the music video for “London Calling,” shot from a boat on the Thames as the band perform on a sinking pier in West London.

While the video appears to be in black and white, the monochrome effect is actually a fuck-up caused by human error. The video’s director, essentially an amateur friend of the band, didn’t think to look up the local tidal patterns: if they had started shooting as intended the boat would have been a good 15 feet below the pier and the video would have been filmed “up Joe’s trouser leg.” They had to wait; it was getting dark and it started raining.

Apparently, at the end of the shoot, all the rain-drenched tech was dumped into the Thames.

Silverton is undeniably British in his prose – he describes a Neil Sedaka song rhyming ‘USA’ and ‘okay’ as “not one of his best,” and it will be interesting to see how this understated humor goes down in the US.

In a manner somewhat endemic to male culture writing, Silverton’s writing can also be frustrating (or “hermetically impenetrable,” to borrow his own phrase). For example, one character is described as being swept along by “jouissance, to use a contemporarily fashionable Lacanian term.”

(Out of stubborn pride, I have not Googled any of the Big Words in that sentence and so cannot shed any light).

His circuitous, informal style reads like your favorite teacher giving a ‘fun’ lesson at the end of term – like watching a Saving Private Ryan in history class. Sometimes it might feel a little hollow, but at the end of the day it’s exactly what you want to be doing.

In general, his youthful enthusiasm for the subject matter wins out, and his dry wit will put a smile on your face. (One example, which made me Laugh Out Loud, is his description of the “clearly overnamed Carter the Unstoppable Sex Machine.”)

Let’s assume that the Clash-heads and the Sinatra-heads, and the Clash-Sinatra heads, are already bought in to the premise of this book. Silverton’s job is to convince a layperson like me that “London Calling” and “New York, New York” – the stories behind them and the stories they tell – are worth reading about today.

And to be worth reading about, these songs must first be worth listening to. Silverton generally steers clear of talking about the music itself; he takes it as given that we know the work, and his brief descriptions of each are as informative as any writing about music can be. But, NYS Music takes its job seriously, and I see it as my responsibility to get up to speed with the material.

“London Calling” was inspired by such rosy topics as nuclear disaster and the specter of catastrophic flooding of the Thames. It is essentially a rock song, driven by Strummer’s words and voice. You can practically hear the dust choking up his throat, and would be forgiven for thinking this was the final, desperate exhortations of a man on his deathbed. But no, Strummer was 27 when “London Calling” was recorded.

If “London Calling” is an air-raid siren, a warning against selfishness and greed, then Sinatra’s “New York, New York” is a wholehearted embrace of it; an aspiration to be “number one, top of the list, king of the hill…” Fuck everyone else, basically.

Two facts about “New York, New York” are surprising. First, it is not originally by Sinatra. Second, it was written for a musical. A Martin Scorsese musical, to be precise, of the same name, with Liza Minelli singing the part. (I am told by a film nerd friend that the movie is his best work. It was a flop.)

Listening to “London Calling” and “New York, New York” in sequence is not an activity for the faint of heart. Try the Clash song first and, by the time you’re halfway through Sinatra, you’ll feel like you’re in the Titanic orchestra, bound by pride to carry on playing 400 feet above sea level as the ship cleaves in two.

Listen the other way round and, by the time Strummer wails “I live by the river” for the second time, you will have become an exhausted cynic, wracked with the urge to complain about something on a local radio station.

Phew. Glad we got that over with.

Being counter-cultural protest music, “London Calling” has aged well. If anything, its warnings of environmental collapse and societal breakdown have only crystallised further. On the other hand, while “New York, New York” still has all the superficial force and charisma it did when it was released more than 40 years ago, it reeks of the hubris of its age.

Thankfully, Silverton is refreshingly iconoclastic about Sinatra, describing (via composer Simon Boswell) his version of “My Way” as a “a hymn whose sole object is the worship of the singer.”

He takes a similarly wary view of New York City itself. In one of his signature coincidence-cum-anecdotes, Silverton unveils the seedy New York link between Sinatra, his “New York, New York”, Ronald Reagan and the “junk bond king” Michael Molken “who embodied the greed-is-good mentality.” (Milken was sentenced to 10 years in prison and fined $600 million for fraudulent trading activity. Readers will be pleased to hear that he was pardoned by President Trump in 2020.)

What makes this book compelling is its many angles: it is part criticism, part memoir, part history lesson, part music theory book, the whole thing tied together by a wellspring of cultural and political trivia.

Silverton tells a personal story of what these songs and cities mean to him, this distinctive narrative giving us the map coordinates we need to really understand the history he paints. This is a difficult tightrope to walk; thankfully the author does not force himself into the narrative when it isn’t needed, something which is not easy to do (trust me).

But if readers come into this book hoping for proof that these two songs are long-lost musical cousins, they are likely to be disappointed. The first explicit link Silverton eventually provides between “London Calling” and “New York, New York” isn’t until Page 43’s confusing roll-call of peripheral London music scene figures. This link comes in the form of one Kosmo Vinyl, “consigliere” to the Clash with a “toilet brush haircut” who ultimately became the conduit between the band Scorsese.

Indeed, the structure of LCNYNY means that it can be hard at times to see what the message is. It eventually becomes apparent that this will not be some ingenious conspiracy theory but a winding journey through the history of the two songs.

For all the overstimulating tangents, big words and music scene in-jokes, Silverton remains true to his brief. Through faithful research and personal experience, he makes it clear that these two songs belong to their cities and their cities belong to the artists.

By intertwining their histories, paints us a picture of “London Calling” and “New York, New York” as moons orbiting their planets. Silverton shows us that these moons – these two irreconcilable juggernauts – are supernaturally attracted; inch by inch, they pull these two great cities closer, imperceptibly closer.

Comments are closed.