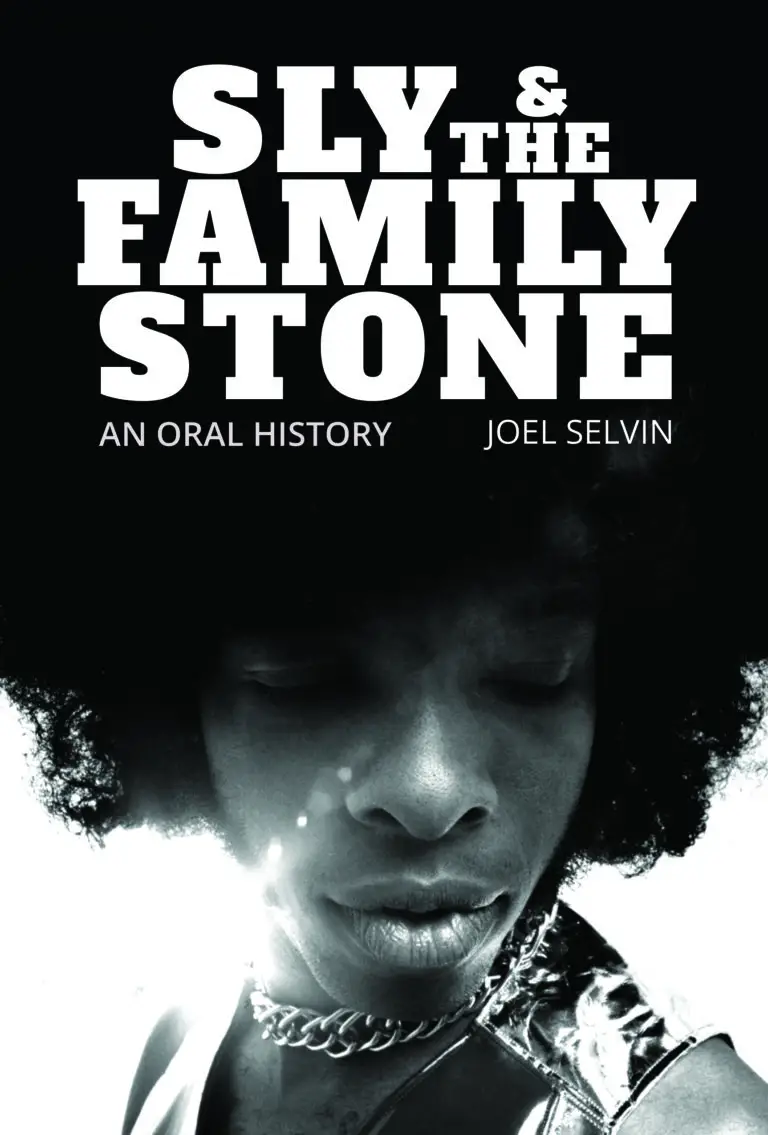

Long considered the definitive account of the meteoric rise and crash-and-burn of the progenitors of funk-rock, Sly & The Family Stone: An Oral History (Permuted Press), has just returned to print in a new, updated edition by Joel Selvin.

The long-time rock critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, Selvin is the author of more than 20 fine books on pop music. They include biographies of Ricky Nelson, Sammy Hagar, The Grateful Dead and Brill Building writer/producer Bert Berns, as well as ones chronicling the Altamont and Monterey Pop festivals, the Summer of Love and 2021’s Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast Cars, and the Myth of the California Paradise, reviewed here.

Sly and The Family Stone was a groundbreaking collective of black, white, male and female musicians. They came to symbolize not only the Woodstock generation’s quest for equality but would dominate the charts for several years running with a string of hits like “Everyday People,” “Dance to the Music,” “I Want to Take You Higher,” “Stand” and “If You Want Me to Stay.” Led by the precocious Sly Stone, their fusion of gospel and rocked-up funk would go on to influence the work of giants like Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and Stevie Wonder and more current artists like Macy Gray, D’Angelo and Childish Gambino. But within a few years, Sly’s promise and grasp on the charts would collapse. Music would take a backseat with the entrance of incalculable drug abuse (coke and PCP mainly), guns, violent hangers-on, paranoia, isolation, inter-band jealousy and “a mean-spirited pit bull named Gun.”

Selvin’s updated version tells the story via interviews with more than 40 of Sly’s associates. These include his parents and family, band members and musical contemporaries like Grace Slick, Mickey Hart, Bobby Womack, Clive Davis and The Beau Brummels’ Sal Valentino. According to Selvin, the key to his unlocking the unvarnished story was locating Hamp (Bubba) Banks. Bubba was young Sly’s best friend and brother-in-law to be, an ex-Marine/pimp/hairdresser who served as Sly’s advisor and sometimes enforcer from his early career through the insane, drug-fueled days of the mid-1970s.

Selvin begins his story with the young Sly cutting his musical teeth singing in churches with his siblings in The Stewart Four, a group with which he first recorded at age 9. Then it is onto his high school bands, The Cherrybusters and The Viscaynes. The latter was an integrated singing group with whom he cut his first composition, “Yellow Man.” A meeting with San Francisco radio legends Tom Donahue and Bob Mitchell would lead to stints as both a popular nighttime DJ on KYA and KSOL and multi-instrumentalist/writer/producer responsible for hits like the Beau Brummels’ “Laugh, Laugh,” Bobby Freeman’s “C’mon and Swim” and the proto-version of “Somebody to Love,” recorded with Grace Slick and her pre-Jefferson Airplane band, The Great Society. Never a wallflower, Sly would strut his success by driving around town in a hot pink Jaguar XKE with two Great Danes in the jump seat.

In short order, he would put together Sly and The Family Stone, with his sometimes-playing partner, sax man Jerry Martini, and drummer Greg Errico, who joined from Sly’s guitarist brother Freddie’s band. Another key addition would be bassist Larry Graham, a wannabe lead guitarist who developed the now widespread “slap bass” style due to lack of drums in a band he played in with his mom. Together with trumpeter Cynthia Robinson from his earlier band, Sly and The Stoners, and his keyboardist/singer sister Rose, the band would make waves in after-hours sets at the Winchester Cathedral in Redwood City and The Pussycat A Go Go in Las Vegas, where Bobby Darin would become a fan. Around the time of their first album, 1967’s A Whole New Thing, the band undertook a residency at The Electric Circus in New York, staying at the legendary rock crash palace, The Albert Hotel.

By March 1968, the single, “Dance to the Music,” crashed the charts, the product of Sly working a new formula solely intent on creating “hits,” after the failure of their debut album. This one is led by his decision to move Cynthia’s memorable shout/call to action from the middle of the song to the beginning, and by putting an accent on Jerry’s jazzy clarinet riffs on the choruses. While in New York, cocaine becomes “a very big deal” to Sly according to one interviewee, when he begins getting mass quantities of it from a friendly dentist.

In the book, Martini talks about “the Sly effect” on audiences. It was a non-stop pulse of collective pure energy from the band, one that would cause a riot at the Newport Jazz Fest in 1969 and power their memorable performance at Woodstock. Even with a 3:30 am start time, Rolling Stone Magazine declared that Sly and company’s 55-minute set “won the battle of the bands” at Woodstock.

Sly and The Family Stones’ true decent into darkness began shortly thereafter. In the book, drummer Errico relates that Sly wanted us “to be the biggest band in the world, but when he got it, he didn’t want it. I think he was scared of it.”

With his and the band’s move to a communal home in Coldwater Canyon, Sly is surrounded by a pack of wild dogs, a collection of guns and some very dangerous goons. Per Bubba, he traveled with “a violin case full of coke,” one that sometimes leaked making him seem like “the girl on the Morton’s Salt package.” He also had a home safe stocked with “500 pill bottles of downs, ups, everything.”

Things really escalate when Sly gets into PCP, or angel dust. He will have days’ long recording sessions at the Record Plant, then later in the attic studio of Mamas and the Papas’ John Phillips old mansion in Bel-Air which he rents. Here, there will be a “no clocks” rule. So Sly would be up in the studio for five days straight working on what would become the album, There’s A Riot Goin’ On, with associates including Ike Turner, Bobby Womack, Billy Preston and Herbie Hancock.

Around this point, Sly and The Family Stones’ life as a touring band begins to be compromised as the bandleader misses show after show. Drummer Errico and band manager David Kapralik will quit, the latter because he was sure Sly would end up killing him due to their mutual drug binges or by a suicide by his own hand. Others credit their leaving to pressure from The Black Panthers to rid the band and its circle of white members. Through Sly’s friendship with The Byrds’ producer Terry Melcher, he will meet the record man’s famous mom, Doris Day, inspiring him to cover her 1956 hit, “Que Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be).” This will become a centerpiece of their final top-ten album, 1973’s “Fresh.”

Selvin’s book provides a deep look at the contributions of others in the band, including the competition with Larry Graham and guitar playing brother Freddie – over music, women and drugs. Per Bubba, “they were always trying to out high each other.” By the end, there were rumors that Larry had put a “hit” out on Sly and vice versa. As he left for the last time, the bassist checked his car for bombs before getting into it. Graham would go on to a successful career; others would not fare as well.

There are some interesting facts about Sly’s next move to New York City and his runnings with neighbors Miles Davis and Geraldo Rivera. And, of course, his marriage to Kathy Silva on stage during summer 1974 concert at Madison Square Garden is covered. There’s plenty of other gossipy goodies including his appearance on the Mike Douglas Show (where Muhammed Ali hits on his wife) and an even crazier one on the Dick Cavett Show, where he barely makes it to the stage. His pit bull Gun runs wild, killing then having sex with a monkey and even attacking his son with Silva. And though there will be much more to Sly’s story, this book concludes with the band breaking up, after they attempt to produce their own string of shows at Radio City in January 1975. The first of which will be only 1/8th full, leading to cancellation of the rest. And the band? They were left high and dry, unpaid with no return tickets home.

There was and continues to be much more to Sly’s story – a seemingly infinite number of attempts to restart his career with the help of folks like Prince and George Clinton and the horrible images of the damage he has done to himself and his singular talent with years of drug abuse.

But as I read this book, I took the opportunity to take a deep dive into the discography of Sly and The Family Stone. The music still has so much power and is so forward-thinking. It is something that reverberates through the DNA of much of today’s R&B, soul, rap and pop, whether the artists know it or not.

Selvin’s latest is the ultimate “Behind the Music” cautionary tale, one made even more tragic when consumed along with a mighty dose of listening to Sly and company’s still groundbreaking music and lyric messages.

Comments are closed.