After 12 years in the incubator, Bob Dylan’s long-awaited book on songwriting, The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster), has finally landed with a very big splash. This, of course, is as it should be as he is, with little doubt, the most revered songwriter of the latter part of the 20th Century, the first and still only rocker to earn a Pulitzer Prize.

As with everything Dylan, The Philosophy of Modern Song, is not really what you think it will. It is not a literal analysis or anatomical study of these tunes as told by their makers. It is something grander, more ambitious and maybe more revealing about Dylan himself – his life’s experiences, observations and opinions.

The book employs 66 widely varied songs as jumping off points for some dazzlingly impressionistic essays. These are his philosophical jams on the subject matter at the heart of each song – from romantic betrayal/divorce to the faith of the Vegas gambler to career crashes, war, alienation and so much more. It’s a Monet, J.W. Turner or other great Impressionist painters take on a book. It’s super misty and foggy but the soft focus of it may impart greater emotional resonance than something photo realistic. In most cases, these elegant prose forwards are followed by a second essay, one that more literally relates to the songwriters and performers, the historical backdrop for the songs and the like.

Per the promotional press release: “While they are ostensibly about music, these are really meditations and reflections on the human condition… a series of dream-like riffs that resemble an epic poem.” Along the way, readers will get plenty of Dylan’s dry and devastating humor, served up with some oddball trivia about the artists and his beliefs on what makes a song great. Want to know how a single extra syllable can ruin a song or how bluegrass is the father of heavy metal? If so, this is the book for you.

The selections in the book demonstrate Dylan’s reverence for many genres of song. There’s old-timey Americana, classic country and Delta and Chicago blues, the crooners of the Great American songbook, Laurel Canyon rock, Motown and Philly Soul, the R&B and rockabilly influenced rock-n-roll pioneers of ‘50s, some classic rock radio staples and even Top 40 kitsch.

Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up” is the perfect “boiling point song, the anthem of an alienated hellcat” per Dylan. He calls the artist a fusion of silent screen icon Harold Lloyd and Buddy Holly, two masters of minimalist precision in their work. Likewise, this song is a “streamlined classic,” one better than others by Costello which Dylan sometimes finds “too wordy” and full of “too many thoughts.” Dylan’s views on the blues classics “Key to the Highway” and “Big Boss Man” are testaments to the power of their architects – Little Walter and Jimmy Reid, whom Dylan dubs “the essence of electric simplicity.” On Elvis Presley’s “Money Honey,” Dylan waxes poetic and a little leftist provides on the value of money. It’s all about power, the difference between rich and power and how we are all equal in the end when we shed the bone suit. His riff on Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” may serve to explain why he is still on his so-called “Endless Tour.” Willie’s version is an update on Kerouac’s hipster/beatnik classic On the Road, in luxury bus vs. Neil Cassady’s ramshackle ‘49 Hudson . Why the road? Because you will never be bogged down by any of life’s trivial responsibilities like doing the laundry per Dylan. It’s all about to the road that leads to the next performance.

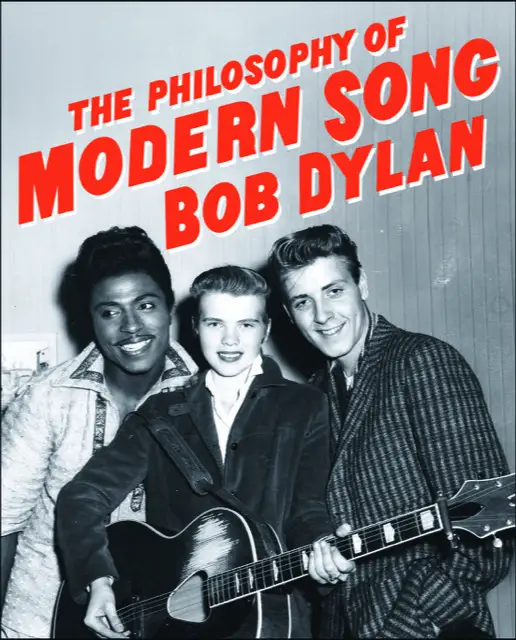

Dylan’s offering on Ricky Nelson’s “Poor Little Fool” sets out to secure Nelson his rightful place on the pantheon of early rockers. Per Dylan, Nelson was the person who really brought this new music to a nation through his weekly performances on his family’s hit TV show, “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet” in the mid-‘50s . According to Dylan, Nelson was “more than Elvis the ambassador of Rock-n-Roll.” This section also charts the starring role “the fool” has had in many eras and genres of popular music, in hits from Hank Snow, Aretha Franklin, Bobby Bland, The Beatles, The Main Ingredient, Elvis Presley, The Grateful Dead and Anthony Newley. Dylan’s book also riffs on a duo of Little Richard standards, “Tutti Fruitti” and “Long Tall Sally.” The former is really Richard “speaking in tongues” about the undercover gay subculture, while the latter provides the platform for a head scratching fantasy about 12-foot-tall ancient Egyptians!

Dylan on The Who’s “My Generation” is a rumination on the “cockiness of youth” and how each new generation will always somehow take from the one before it … and resent the fact! The Eagles “Witchy Woman” is the runway for a rant on the kinds of women you should avoid, “a hallucinogenic amalgamation of succubus and thaumaturge.” It’s also a deep dive into the life and end of the legendary New Orleans voodoo queen, Marie Laveau. With his study of “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” Dylan addresses how being misunderstood and getting lost in translation “ruins your enjoyment of life.” There’s cool trivia here about how the label that put out Nina Simone’s classic version, ESP, was first founded to help spread the new universal language, Esperanto, before it became the home to avant-garde jazz greats like Albert Ayler.

In the chapter on “It’s All in the Game,” we learn how a melody created by a man who would become Vice President to Calvin Coolidge made the hit parade. Here, Dylan spouts on the history of American politicians as musicians, referencing Nixon’s piano chops and Bill Clinton’s yakety sax to name a few. This chapters contains what I think are the most unfortunate collection of words in the book, when he calls former Arkansas governor and Fox News staple Mike Huckabee “an accomplished bass player.”

The ‘70s Stax Records classic, “Cheaper to Keep Her” by Johnnie Taylor, is a song reflection what Dylan calls “the school of street wisdom.” Perhaps a reflection of his own experience, Dylan uses it to rail against “the $10 Billion a year divorce industry” and lawyers in “the business of family destruction.” His solution? Embracing polygamy and having only as many children as you can afford! And speaking of questionable occupations, Dylan’s take on Cher’s quasi-novelty hit, “Gypsys, Tramps and Thieves,” concludes with him saying that these are “the three types of people” a person might have the most fun having dinner with.

For me, Dylan’s most eye-opening take came with Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart.” To Dylan, it’s a song of nuance, one that can be viewed from two perspectives. First, and most obvious, is the person who has been cheated on. But for Dylan, maybe the song is really or also about the cheater, the person who is questioning his own compulsion to be unfaithful again and again?

Credit must go to whoever art directed this long-awaited book. The text is complemented with over 150 curated photos which serve to set the time and emotional tone for Dylan’s subjective, profound and sometimes humorous investigations of some our most beloved and underappreciated popular songs.

Comments are closed.