The 1970s were heady times when it came to bass innovators.

In America, Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke not only reinvented how the electric bass was played but pushed it front and center on stage and in recordings with their respective jazz fusion juggernauts, Weather Report and Return to Forever.

Over in Europe, a German named Eberhard Weber was doing much the same, just sans Jaco’s rock star posturing. The quietly intense, uber cool Weber’s instrument of revolution was a 5-string, electrified upright bass of his own design. His lush chordal-flavored accompaniments and fleet high-register soloing were the centerpiece of legions of albums with greats like Jan Garbarek, Gary Burton, Pat Metheny, Ralph Towner and his own quartet Colours, all emanating from Manfred Eicher’s masterfully curated ECM Records. Like Jaco, Weber’s singular sound would find a home beyond the jazz world. It would be deployed by the edge-pushing Kate Bush of four acclaimed albums made during her 1980s heyday.

But all that came to a halt in April 2007. That was when the always furiously busy Weber suffered a stroke on the way to a gig that put an end to his 40-year playing career.

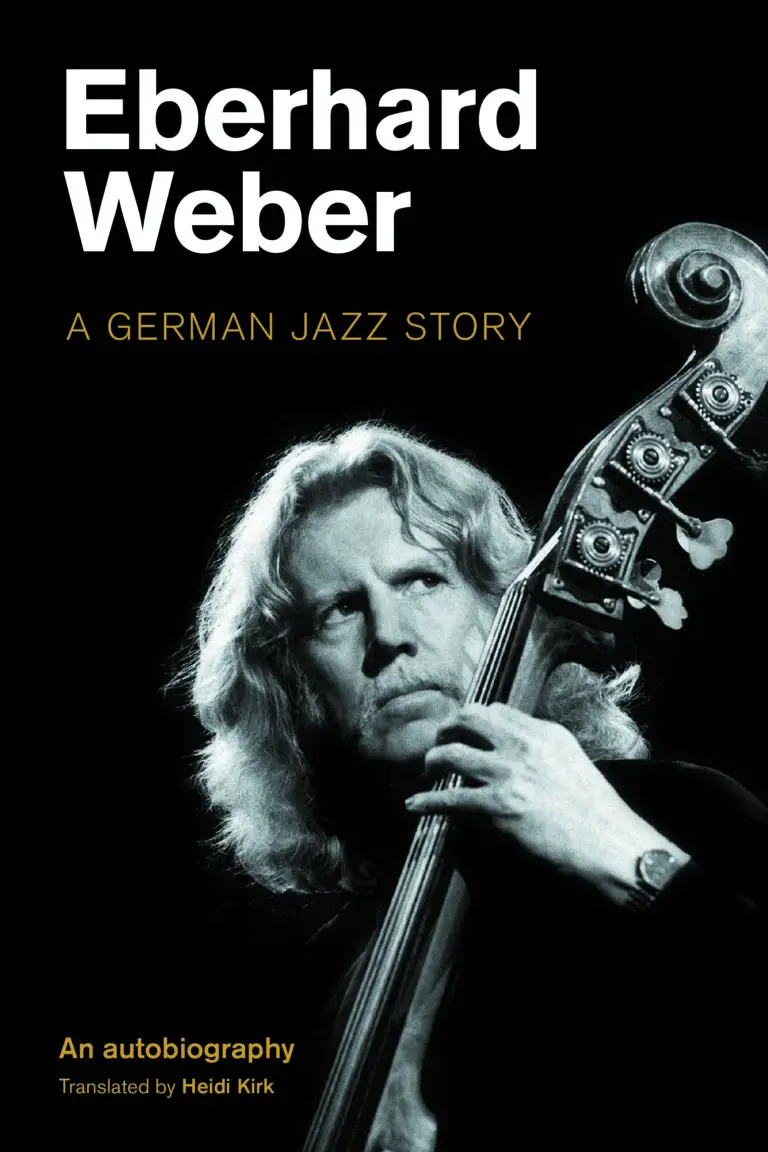

But now the maestro is back with Eberhard Weber: A German Jazz Story (Equinox Publications UK). At a little over 170 pages, it is a deceptively slim memoir containing more wisdom about creativity and the life of a working musician than many cinder block-thick music bios. There are probing discussions of what jazz really is and the arts of composition and collaboration, as well as a dressing down of the jazz conservatory complex, drummers who keep pling their cymbals after the last chord and his own “inadequate twisted finger technique.” He also addresses why there is no such thing as “the perfect instrument” and how one fiddles forever to try and work around it.

Weber begins his story at the end: with the saga of the stroke that has robbed him of his ability to play. It is a true clusterf*ck of a tale. There are the on- and off-again symptoms that he didn’t recognize as a cause for concern until it was too late. There’s a power outage that meant they couldn’t survey the full damage with an MRI until the morning after he checked into the hospital, when he awoke in a much more serious state with his left side now completely paralyzed. And like in the U.S., there is insurance industry sleight of hand which means his rehab is delayed, perhaps posing a terminal blow to his recovery.

Weber discusses his birth in Stuttgart during WW II, his childhood under the subsequent American occupation and hustling candy bars from friendly GIs. He was the son of a professional cellist, pianist and educator who played with orchestras but also banjo in dance bands to make ends meet. An influential memory shared listening to his father and his friends rehearsing string quartets and playing piano while lying under the instrument, something he is sure helped to shape his own love of deep sounds. At eight, he began playing the cello himself. By 15, he discovered Bill Haley, boogie-woogie and Dave Brubeck and switched to the upright bass. After his callouses hardened, he began working steadily at society gigs and playing that uniquely German brand of sentimental pop called Schlager.

In his late teens, Weber joined together with pianist Wolfgang Dauner. It was a partnership that would last 10 years, through infatuations with the piano trio music of Bill Evans and bassist Scott LaFaro through to the “Free Jazz” experiments inspired by the political upheaval of the late 1960s. The latter featured some pretty outlandish “happenings.” In one, the band played with a completely naked drummer. In another, Dauner had the bright idea of slaughtering a chicken on stage, for the sound and spectacle, something that Weber nixed. The bassist also recalls an incident where Joachim Ernst Berendt, the so-called “Pope of German Jazz,” stopped a recording session “just because someone was playing harmonies.” With his reputation spreading, Weber became a “telephone bass player” for the MPS, Germany’s first important jazz label. He is summoned with last-minute calls to do sessions with world class artists like Joe Pass and Baden Powell. Around this time, he also makes a big impact in the emerging world of jazz rock on numerous recordings with guitarist Volker Kreigel.

Throughout these years, Weber held down a day job as a photographer and commercial producer for various ad agencies and, ultimately, IBM. It is not until he met and married his wife Maja in 1968 that he gave up his day job, learned piano, set up a small home studio and began to compose the harmonious chamber jazz that will cement his reputation.

No discussion of Weber would be complete without a deep dive into the world of ECM Records. The brainchild of Manfred Eicher, ECM began as a “counter movement to Free Jazz,” a label dedicated to producing records that are “the most beautiful sound next to silence” per its motto. Weber was one of the foundational artists in the ECM fold. It’s an illustrious roster of creators all practicing harmonious, classically-inspired, coolly minimalist jazz, names like pianist Keith Jarrett, saxman Jan Garbarek and Norwegian Avant guitar god Terje Rydal, who have remained with the label for five decades and counting. One signature of ECM and Weber’s production is the crystalline sound quality conjured by engineer Jan Erik Konghaug at the label’s home base of its early years, Talent Studios in Oslo (Note: Sorry for stealing the mailbox label for my electric mandolin case during a visit/pilgrimage to Talent in 1981!). Another is the minimalist and very beautiful cover art. Many showcase the wonderful photography of masters like Joel Meyerwitz and paintings of artists like Maya Weber, whose work adorns many discs by her husband and other ECM stars.

After guesting on tour and records with ECM artists like Gary Burton and Ralph Towner, Weber would make his debut as a bandleader and composer with Colours of Chloe. The 1974 album helped to define the ECM sound — picturesque, romantic, at times rhythmically involved, at others minimalistic and harmonically abstruse. It was awarded the Great German Record Prize, record of the year for all genres of music. It inspired Weber to form his classic Colours quartet with veteran saxophonist Charlie Mariano, pianist Rainer Bruninghaus and British drummer John Marshall of Soft Machine fame.

Weber’s quartet produced some remarkable work through its dissolution in 1981, including the albums Yellow Fields, Silent Feet (my personal favorite with the side-long epic “Seriously Deep) and Fluid Rustle, which helped introduce the world to guitarist Bill Frisell. Due to ECM’s marketing success in America, Weber and band would tour the U.S. twice a year in this time, on bills with other label stars like Keith Jarrett and Terje Rypdal.

Feeling that his need to compose was somewhat satisfied, Weber disbands Colours and joins up with Jan Garbarek for a run of remarkable recordings and world touring that will last for 25 years, until Weber is felled by his stroke. Weber will still have time to tour and record on his own, in settings with small bands, orchestras and solo bass albums. A person has not truly lived until they have been bathed in the sublime textures of Weber’s solo album, Pendulum, a masterpiece showcasing his subtle use of delays and intricate overdubbing.

Weber’s book then detours into discussions of many things that impact the life of touring musicians, e.g., how drugs and jet lag can effect performance and literally kill you, the high and lows of hotels, concert catering, sound checks, amp malfunctions and the like.

Weber concludes his story by updating fans on his present condition. He feels lucky to have retained his memory and speech post-stroke and tells how it can sometimes trigger bouts of uncontrollable laughter in victims. He shares how he considered going on with limited ability but gave it up, especially after he inadvertently backed his wheelchair into and toppled over the 5-string upright bass he has played for decades, causing its next to snap (Note: It was ultimately repaired).

In the end, he talks about learning how to enjoy silence now that the pressure to perform at a world class level is off. ”Music isn’t relaxation to me. It’s tension and concentration.” Weber also talks about coming to terms with old age and a quandary common among musicians – focusing too much on playing and not thinking about the practicalities of securing a retirement when the music is over by perhaps teaching like his father.

“There is another reason, an entirely profane reason, why I never wanted to take on a professorship,” concludes Weber. “I have always been of the following opinion (in a mysterious way, it has taken on a new meaning today): “I can’t play the bass. But I know how it’s done!”

Comments are closed.