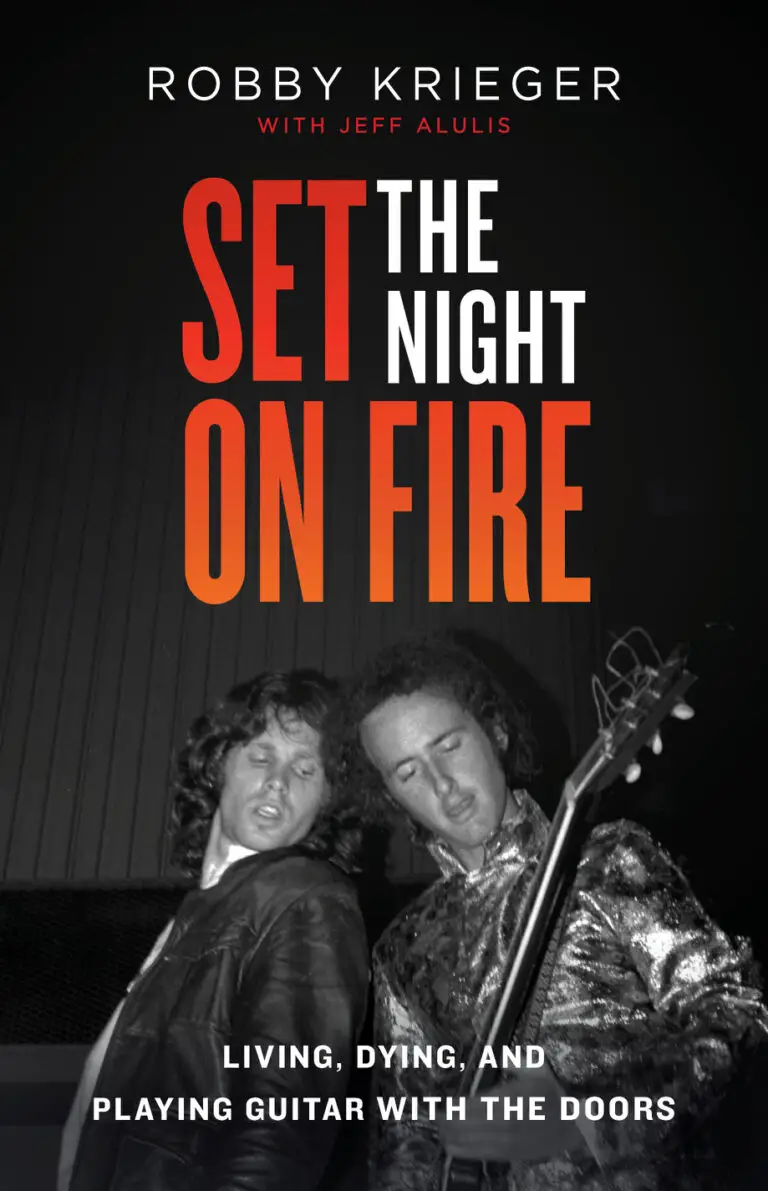

Robby Krieger was far more than a simple guitarist for The Doors. For all the acclaim laid upon Jim Morrison as rock’s poet laureate, it was Krieger who almost singlehandedly wrote the music and words for some of their biggest hits including “Love Me Two Times” and the career-launching “Light My Fire.” A master of restraint in this playing, the reserved Krieger has likewise held his tongue for five decades on providing his take on his mythic band. Now this and much more is contained in a new book, one as sprawling and emotionally topsy turvy as their classic Oedipal-themed tune “The End” – Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying and Playing Guitar with The Doors (Little Brown).

No band is as shrouded in murky mythology as The Doors. First off, is Jim Morrison really dead? Did he pass peacefully in a warm bath in his Paris apartment or was it an O.D. courtesy of a European Count/heroin dealer in a nightclub toilet? Did he really expose himself on that stage in Miami or double-cross Ed Sullivan when he sang the word “higher” during their appearance on America’s top TV show? Did he have a secret wedding to a Wiccan witch? Was he an insatiable sexual satyr or just an impotent poser? With earlier books by band intimates like keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer John Densmore and teenage gopher-turned-manager Danny Sugerman and filmmaker Oliver Stone’s fantastical take, the legends are many and still multiplying. They are thick, twisted and juicy, but not always very factual.

The Doors themselves are not the whole story covered here. Krieger’s comprehensive autobiography also provides many dramatic facts about his budding juvenile delinquency and teenage drug bust, his musical apprenticeship as a flamenco guitarist before his immersion in blues as well as his post-Doors decades, including his lengthy struggles with heroin addiction and cancer.

Krieger’s story jumps around in time and is all the better for it. Unlike Morrison who disowned his family, Krieger’s parents were supportive of his musical aspirations. They bought him his first guitars, carted his early bands to gigs and bailed him out of teenage run-ins with the law (vandalism and that drug bust). Importantly, they also provided a room where the fledgling Doors could write music and practice in their early days.

Naturally, this book has a lot of Morrison. But unlike drummer John Densmore’s sometimes bitter tome, Krieger’s is largely sympathetic in its portrayal of the Lizard King. Morrison is given credit for never departing the band for a solo career when it was suggested by early management – a duo he insisted be fired for the transgression. He was also the member who suggested a four-way split on publishing, one that insured they and their descendants would remain very rich men. Jim is applauded for his lyric and conceptual contributions, stage craft and his voice, which was completely unimpressive at first to the guitarist. Of course, there is much said here about his lunacy, obstinacy and decent into addiction. There is his love of walking on window ledges, his massive consumption of LSD and alcohol, his predilection for missing shows and even his unexpected delight in getting an STD! In his skewered logic, Morrison thought it might make him feel closer to the disease-ridden 19th-century French poets he so loved.

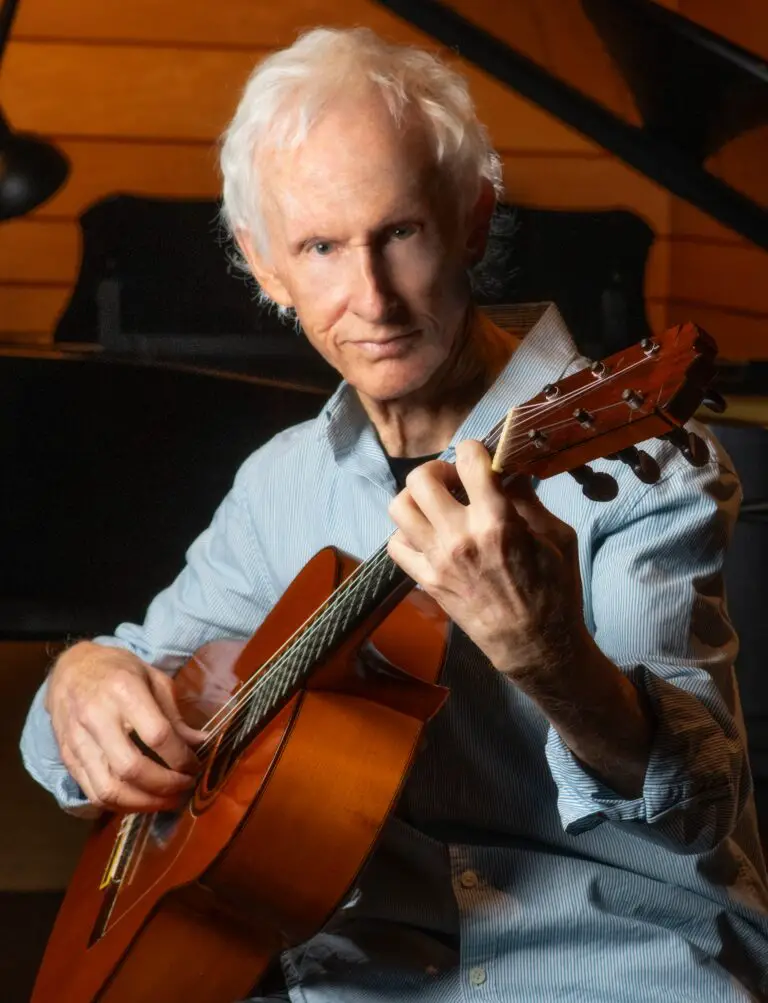

There is much here about Krieger and his band’s music making – an album-by-album critique of how they wrote, arranged and recorded these classics. But it is Krieger’s musical development – his early exploration of flamenco guitar and then the works of John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar – that provides insight into what makes him such a distinctive musician. While Krieger could swing the barroom blues cliches with best of them (see the L.A. Woman album), the sounds he brought to The Doors were wholly unique in the rock of his era – flavored with the Spanish, modal and raga airs purveyed by his above inspirations.

Krieger is self-depreciating when he recalls the criticisms laid on him for having “the worst hair in rock and roll.” He also straightens out the mystery behind the black eye he displayed uncovered during an appearance on “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.” There are also funny takes of some the oddball hangers-on to the band. These included Cigar Pain. This was a guy who would sing through the air conditioning vent at their rehearsal studio/office, somehow who purportedly put out a cigar on his vocal chords to sound more like Jim.

The guitarist provides his views on the mystery behind Morrison’s death and why it perpetuates (hint: it was likely his more promo-minded bandmate Manzarek who kept it alive). The band did continue on for a while as a three-piece with little success. Robby reveals that they considered offering the lead singer role to Joe Cocker and Paul Rodgers, and not Iggy Pop as is often referenced, before calling it quits.

Krieger’s post-Doors life has been filled with more music and some real personal challenges. Immediately after The Doors, he was a part of the poorly named The Butts Band before heading into a more jazzy, eclectic direction in his solo work and periodic reunions with Manzarek as “The Doors for the 21st Century.” He pulls no punches on his decade-plus additions to heroin and cocaine and his cancer battle. Fun fact for the TMZ set? It was a distant cousin of the famed Kardashians who taught Robby and his wife Lynn to shoot up.

Truth be told, The Doors were never one of my favorite bands. Sometimes I truly love them, sometimes I don’t (mostly when Manzarek’s Vox Continental Combo organ gets super cheesy and Jim’s prose veers into high school bad). But Krieger’s book made me listen with new ears to many of their tunes, especially the lesser-known ones. And better than any book before it, it provides a largely hype-free and believable view of a band whose music and myth shines on brightly for many generations of music lovers.

Comments are closed.