No group may have shifted the direction of rock music more radically than The Band did at the close of the ‘60s. With their 1968 debut, Music from Big Pink, the Canadian-American quintet single-handedly put an end to the abstraction and overload of psychedelia, much like Nirvana’s blast of grunge freshness did to the Hair Metal bands in the early ‘90s. Big Pink put the accent on authentic, no-frills, stripped-down songcraft – a proto-Americana that fused country, blues, folk, R&B, and roots rock with lyrical narratives that spun out like Great American novels. It was a shot across the bow of the frothy rock conventions of the time, a milestone that made everyone from The Beatles to The Grateful Dead to Eric Clapton rethink their approach to songwriting and recording.

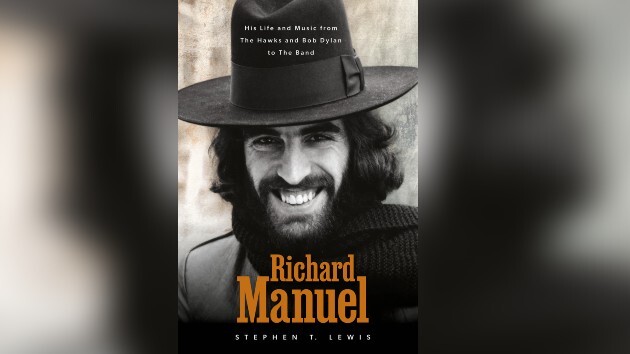

While The Band’s chief songwriter, Robbie Robertson, and its charismatic singing drummer, Levon Helm, were the most visible members of this group, it is the uniquely talented and ultimately ill-fated singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist Richard Manuel whose contributions now seem the most lost to time. But that may now change thanks to the publication of Steven Lewis’s wonderfully comprehensive and insightful biography Richard Manuel: His Life and Music from The Hawks and Bob Dylan to The Band (Schiffer Publishing).

Lewis traces Manuel’s journey from his youth in Stratford, Ontario to his glory days in Woodstock, Los Angeles and beyond, beginning with his first band, The Revols, and continuing to his time with Robertson, Helm, Rick Danko, and Garth Hudson in The Hawks, the group would later become The Band. He then charts The Band’s live and studio work with Bob Dylan, including the creation of some of their greatest collective songs in the basement of Big Pink. This is followed by a deep dive into his group’s long and storied career, concluding with the legendary The Last Waltz concert and film. This is followed by his failed attempt to pursue a solo career and his work with the reconstituted but Robertson-less version of The Band, a chapter that would conclude with his suicide while on tour in Florida in March 1986.

Manuel’s “sweetly soulful” vocals, rhythm-heavy piano playing, and unique songwriting sprang from an early love of giants like Ray Charles, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and Howlin’ Wolf. His love of harmony stemmed from his childhood singing in church, and although he briefly took piano lessons, he never learned to read or write music. He would also develop a unique style of drumming that would be featured on favorites like “Rag Mama Rag” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” Manuel would earn the nickname “Beak” for his outstanding proboscis and a taste for drinking Grand Marnier cognac from Bo Diddley. The latter would only escalate his struggle with drinking and hard drugs, which would undermine the early promise most present on The Band’s debut album, where he wrote and sang many of the standout tracks. Lewis’s book also greatly benefits from the cooperation of Manuel’s family, friends, and fellow musicians, including interviews with and the recollections of star intimates like Clapton and Van Morrison.

Unlike many gossip-heavy music biographies, this author also provides a detailed analysis of much of the music Manuel created during his lifetime. This encompasses album tracks, unreleased studio recordings, demos, as well as bootlegs and soundboard tapes of live shows. There’s also some fun trivia about some offbeat sessions Manuel and his counterparts did with a pre-fame Carly Simon and Tiny Tim.

As someone who lives a 1/3 of a mile from Big Pink, I particularly loved the info Lewis shared about The Band’s time in Woodstock. After their 1966 UK tour with Dylan, a druggy and tumultuous affair chronicled in the film Eat the Document, the quintet moved to Big Pink in February 1967, paying the princely sum of $300 a month. Their days would begin early, as Dylan arrived after dropping off his kids at school. They would wake to the smell of Dylan brewing coffee as he banged out lyrics on an old Olivetti typewriter in the living room. Their sessions in the home’s famous basement would yield 150 – 200 recordings and many monumental originals, including “Tears of Rage,” the opening track on Music from Big Pink, co-penned by Dylan and Manuel.

Manuel, like his bandmates Danko and Helm, was a terror behind the wheel from his teens. He chalked up a scary legion of fender benders, including one where he wrecked the brand-new Ford Mustang that Robertson had just purchased for his wife, Dominique. Lewis regales us with many tales of Manuel’s social life in Woodstock – his epic partying at long-gone musician haunts like Deanie’s and Sled Hill where he complemented his ever-present Grand Marnier with Go Fasters, a brain- and palate-bending concoction of vodka, 7-Up, and brandy. There are recollections of pilgrimages to Big Pink by rock royalty like Beatle George and Clapton. The latter would record a duet with Manuel on his 1976 album, No Reason to Cry, and was planning a duet album with Richard at the time of his death. Lewis also touches on the darker chapters of Richard’s life, his long battle with heroin, his failed marriage, and his on-and-off-again relationship with the infamous Cathy Smith, the Canadian groupie/dealer who would later be held accountable for the overdose death of comedian John Belushi. Manuel’s relationship with the Woodstock police was so cordial that they presented him with a laminated photo of himself on the Ed Sullivan Show that he used as a license.

Music from Big Pink would be the apex of Manuel’s contributions to The Band. He has equal songwriting credits with Robertson, penning three songs and one co-write with Dylan. He also sang lead or co-lead on seven of the album’s 11 tracks. When The Band decamped to Los Angeles to record their sophomore album in Sammy Davis’ pool house, Manuel would co-author three songs with Robertson, including the fan favorite, “Whispering Pines.” He would sing lead or co-lead on five of the album’s 12 tracks. Their third album, 1970’s Stage Fright, would house his final two co-writes for The Band. Tellingly, it also features “The Shape I’m In,” a Robertson tune sung by Richard, which was Robbie’s not-so-subtle plea for him to straighten out and get back to business. This coincided with the time when The Band’s heavyweight manager, Albert Grossman, would turn his attention to increasing the profile of Robertson after losing his contract representing Dylan. This is especially evident in their swansong, the concert film The Last Waltz, which vastly underplayed Manuel’s role in the group and featured none of his originals.

Richard’s life after The Band was a tough go, a career that was compromised by his seeming laziness, self-doubt, and, of course, all the drugs and drink. While living in Los Angeles in the stable featured in the TV series Mr. Ed, Manuel proudly erected a six-foot-tall tree out of empty Grand Marnier bottles. But even in the most diminished live setting and condition, Richard could rise to the occasion to belt out stunning versions of beloved chestnuts like Ray Charles’ “Georgia On My Mind” and Bobby “Blue’ Bland’s “Share Your Love with Me,” the latter featured on The Band’s spectacular covers album, Moonlight Matinee. He made some valiant but ill-advised attempts to harness his addiction, substituting cocaine for heroin and even going on the wagon. It was a fall off the wagon that Lewis writes played a role in his decision to take his life while on tour.

Kudos should also go to the book’s designer. It is lavishly illustrated with superb graphics and photos chronicling Richard Manuel’s life from his childhood to his passing, secured by Lewis, a master researcher and archivist if there ever was one.

While Lewis has written about music for twenty years and hosted the long-running Talk of the Rock Room website, this is his first full-length book. It is a mighty accomplishment that does what a great music biography should. It provides rich insight into the creation of Manuel’s wonderfully soulful body of work and its impact on the history of rock and his better-known contemporaries. It is a long-overdue epistle that propels a most deserving and sorely overlooked talent back into a spotlight he so richly deserves.

Comments are closed.