Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” is a book that I will never forget. The heart-wrenching narrative of Cudjo Lewis, the only living survivor of the transatlantic slave trade at the time of its writing in 1931, offered a glimpse into an important, yet widely unheard narrative. The story, told through three months of conversations between Zora Neale Hurston and Lewis, sheds light on the narrow binaries associated with understandings of the transatlantic slave trade.

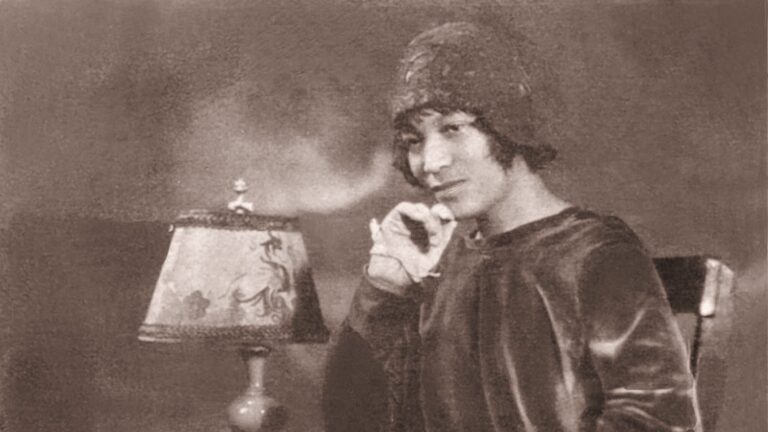

Zora Neale Hurston, the author of Barracoon, crafted a raw, engaging masterpiece simply by giving Lewis a platform to tell his story, while preserving his essence within it – written in the vernacular, I felt as if I could hear Lewis’ voice as he spoke of unimaginable horrors. Hurston’s dedication to providing platforms for black voices and perspectives was not limited to Baracoon. Hurston’s spirit, themes of race, gender, and identity, and efforts to preserve and celebrate African American folklore and traditions was present in all her works, hence her influence in the Harlem Renaissance.

The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance, a cultural, social, and artistic movement that took place in early 20th century Harlem, a hub for African American culture and creativity, marked a significant upsurge in African American literature, music, art, theater, and intellectual thought. Hurston is often regarded as an embodiment of the Harlem Renaissance due to her significant contributions to various artistic and intellectual aspects of the movement. Her literary contributions captured the essence of African American culture and experience. Hurston’s anthropological fieldwork was dedicated to collecting stories, songs, and rituals from African American communities as her individualistic, independent spirit sought to break away from traditional constraints. She collaborated with other notable minds of the Harlem Renaissance, and above all else, was dedicated to providing a platform for black voices and perspectives.

Hurston truly embodied the essence of the Harlem Renaissance through her literary, cultural, and intellectual contributions. To understand Zora Neale Hurston as an integral figure of the Harlem Renaissance, it is important to first understand her origins and experiences that would influence her role in the movement.

Early Life

While Hurston was born on January 7, 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, her childhood centered around her home in Eatonville, Florida, after her family moved there when she was a young girl. Eatonville, a rural community near Orlando, was established in 1887 as the nation’s first incorporated black township by 27 African American men.

Growing up in an incorporated black township, Hurston possessed a unique background that would separate her from the vast majority of African Americans who were subject to the country’s notions of inferiority. Hurston was constantly surrounded by black excellence and achievement – black men were lawmakers with the town hall run by black men, including her father, John Hurston. Black women, like her mother Lucy Pots Hurston, were also in leadership roles, directing the Christian curricula at Sunday School. Everywhere Hurston looked, black excellence was reflected, even in the village store, or on porches full of black men and women engaged in conversation, sharing stories and knowledge.

It was through this experience that Zora’s childhood was relatively happy, with more examples of black excellence and power in her small village than many other young black girls across the South could fathom. However, this happy childhood came to an abrupt end when her mother died in 1904, when Hurston only 13 years old. Hurston’s once close, family unit quickly dispersed – her father’s grieving period was short, marrying a younger woman very quickly after the death of his late wife. Hurston’s father never seemed to have time for his family or children after this new marriage, leaving Hurston isolated and lonely, her once idyllic childhood from a different lifetime gone entirely. Hurston would soon be forced to pack her bags and leave her home, wandering from one family member to another.

The following years were full of their own trials. Once Hurston moved to Jacksonville to live with her brother and sister, she quickly realized the harsh realities of the American South as an African American outside of her township. As a black girl, she was not able to get much education, her only prospects in the eyes of society to work as a maid. Hurston worked a series of jobs to get by, and struggled to complete her schooling. Her brother Robert became a practicing physician and invited her to care for his children. While he provided a roof over her head, he did not encourage her to complete her schooling. Hurston soon ran off with the Gilbert & Sullivan traveling troupe as a maid to the lead singer.

As dismal as this period was, Hurston’s immersion in the world of theater would influence her future role in the Harlem Renaissance, as drama would become a great passion in her life. It is widely thought that Hurston, though she grew popular through her novel writing, would have loved to become a dramatist. However, Hurston’s connection with the theater company ended in 1916 in Baltimore. Fortunately for Hurston, her sister Sarah resided in Baltimore and welcomed her into her home.

In 1917, a 26 year old Hurston had yet to complete high school. It would soon become clear that living in Baltimore with her sister would change Hurston’s life for the better. She was finally able to attend high school and enrolled at Morgan Academy. She famously presented herself as a teenager to qualify for Baltimore’s tuition-free public education system, deliberately representing herself a decade younger with a birth year of 1901, at the age of 16. This was not a temporary measure – Hurston would forever present herself as 10 years younger than she actually was.

Joining the Movement

After graduating highschool in 1918, Hurston enrolled at Howard University. This marked a significant turning point in her life, as she was now able to fully harness her potential and engage likeminded peers. Hurston’s fierry intellect, and infectious sense of humor amongst many other talents worked to her advantage, allowing her to elbow her way into the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Hurston took full advantage of the opportunities presented to her at Howard University. Lorenzo Dow Turner, the author of Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect, taught her African words, Montgomery Gregory directed her as a member of the Howard Players, and Hurston joined a literary club sponsored by Alain Locke who, recognizing her talent, strongly encouraged her to publish works in the Howard University journals. Through this, she met many other writers, including Bruce Nugent, Jean Toomer, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and Jessie Fauset, all of whom would become part of the core of the Harlem Renaissance.

By submitting her work to journals, Hurston jump started her writing career and would soon be recognized for her talent. In 1924, she sent a short story titled Drenched in Light to Charles S. Johnson, the editor of the Urban League’s publication, Opportunity. In addition to being published, her story earned second prize in the Opportunity’s annual literary contest. Drenched in Light took place in Eatonville, her home town, taking her personal experiences and making them into a work of art. Recognizing her potential, Johnson urged Hurston to move to New York City to join the creative minds behind the ever growing Harlem Renaissance. Soon enough, Hurston found herself in Harlem.

In 1925, at the next Opportunity awards banquet, Hurston won several more prizes for her work, and also met notable Harlem Renaissance influences including Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Carl Van Vechten, Fannie Hurst, and Annie Nathan Meyer, people who would prove to support her time in New York. It was Meyer, one of the founders of Barnard College, who would help Zora get accepted and awarded a scholarship in 1925. Hurston began to study anthropology under Franz Boas, considered the father of modern anthropology.

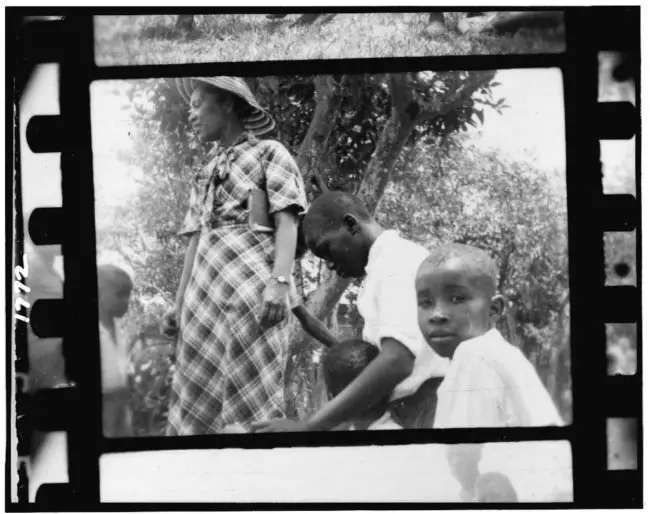

Hurston’s time at Barnard would prove to have a notable impact on her life and career. Studying under Boas, she learned a great deal about his beliefs in the distinctive culture of African Americans. Boas urged Hurston to do fieldwork in her hometown of Eatonville to preserve her heritage and illuminate black voices and experiences, a practice that would soon become a theme throughout her works. Hurston’s field work, along with her passion and talent for writing, merged. With personal knowledge of her home community and its members, she was able to further richen her stories, creating compelling, masterful pieces. At this time, Hurston truly devoted herself to promoting and studying black culture.

Despite Hurston’s passion and skill, she was constantly weighed down by financial insecurity. In 1927, Hurston had no choice by to accept the aid of Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy white woman who took an interest in Hurston. Mason was willing to fund Hurston’s folklore field studies among African Americans in the South. However, there was a catch. Mason would fund these expeditions as long as she retained control over how the material was utilized.

The decision to accept Mason’s offer did not come without consequences. Hurston would eventually break her academic ties with her professors at Barnard, and would grow more and more worn down by Mason’s controlling nature.

Despite how difficult her arrangement with Mason was, some good came out of it. Hurston found her own style once freed from academic method, writing about her own unique interests without restraint. Hurston would further explore African American culture, finding herself intrigued by hoodoo. She traveled to New Orleans to learn more about the practice and study the life of priests there. In her eyes, hoodoo was a practice in which women were allowed to play a prominent role in its rituals, an uncommon occurrence in Hurston’s time. Perhaps this served as a reminder of the black women in leadership roles from her childhood.

After graduating from Barnard in 1928, she pursued graduate studies in anthropology at Colombia University. Hurston continued her field work during this time, and would soon find herself at the forefront of the Harlem Renaissance.

Renaissance Works

In 1930, Hurston collaborated with her friend and fellow Harlem Renaissance figure Langston Hughes on a play titled Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life in Three Acts. Throughout her career, Hurston’s works largely reflected her upbringing and passion to illuminate black voices. In 1934, Hurston published her first full novel, titled Jonah’s Gourd Vine, a work which was well received by critics for its accurate, genuine portrayal of African American life.

Hurston’s newfound success was paired with newfound stresses. In the early 1930s, as the country was heading towards the Great Depression, Hurston’s relationship with Mason came to a breaking point, leaving Hurston without any income. Hurston put her talents to use, producing a folk musical based on her memories from her childhood in Eatonville. The play, titled The Great Day, debuted in 1931, but was forced to close. Despite this, Hurston continued on with her theater work in the south at Florida’s Rollins College in Winter Park. Her two productions in 1933 and 1934 featured many people from her hometown as actors.

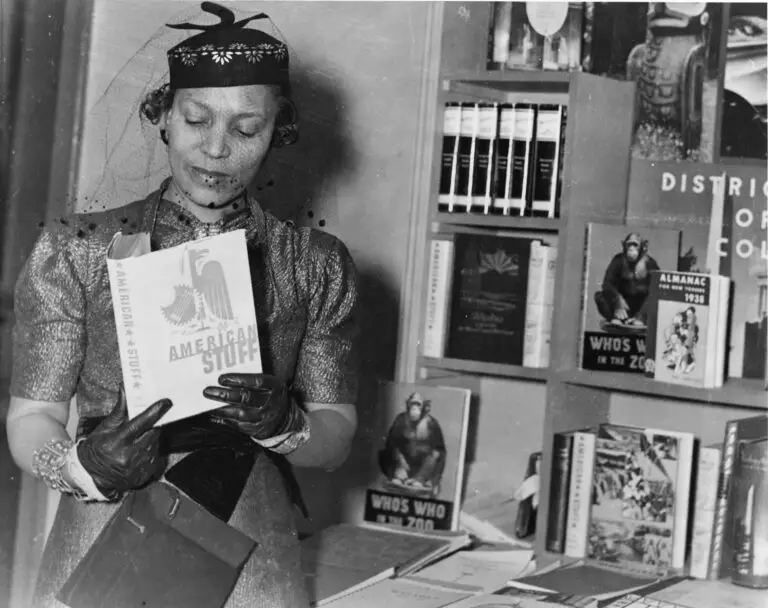

Hurston’s theater productions at Winter Park proved to be even more important than Hurston could have imagined. The theater director Robert Wunsch read Hurston’s short story, The Gilded Two Bits, and sent it to Story Magazine to be published. This publication caught the attention of publisher Betram Lippincott, who asked Hurston if she would submit a novel to him for publication. In 1934, Hurston wrote Jonah’s Gourd Vine, a novel that was published months later. Lippincott would also publish another notable work of hers, Mules and Men in 1935, a study of the folkways among the African American population of Florida.

Hurston would find that the late 1930s and early 1940s would mark the peak of her career, combining her interests in drama, fiction, and anthropology. Following the success of her novels published under Lippincott, Hurston was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1936, allowing her to continue her field work beyond the American South into Jamaica and Haiti. It was here that she would write another novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God , which would be published in 1937, along with Tell My Horse in 1938, both of which blended her travel writing and anthropology studies based on her investigation of Caribbean voodoo practices. By her 1939 publication Man of the Mountain, Zora had officially established herself as a major author, the works in the late 1930s considered masterpieces.

Later Life and Legacy

Following her peak, Hurston was on the faculty of North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) for many years, along with serving as a member of the Library of Congress staff.

While Hurston held considerable promise early in her career, her period of success would come to pass. Hurston once again found herself struggling for survival. She worked at the Works Progress Administration in 1938, and despite her desperate situation, found ways to continue on with her mission. She submitted interviews with former slaves to The Florida Negro, interviews which would only be published years later. When the WPA dismantled, an unemployed Hurston found her relevancy had diminished, her novels no longer approved for publication.

Luckily, Lippincott encouraged Hurston to write an autobiography. Dust Tracks on a Road, published in 1942, worked as a saving grace for Hurston. Suddenly, her desperate situation had been transformed into a revival. Her autobiography earned several awards and recognition and her career would further succeed following her collaboration with Maxwell Perkins, the Scribner’s editor of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe. The project came to an abrupt end when Perkins passed away. The work that Hurston did publish was unlike any of her previous works as her and Scribner’s 1948 work featured an all-white cast of characters, nothing like the characters inspired from her hometown.

Once again, Hurston’s recognition would fade, as she was barely remembered by readers by the time of her death. The next decade of her life largely reflected her earlier years, working as a maid while selling articles to magazines. She struggled financially until her death in 1960.

While the last chapter of Hurston’s life is hardly a reflection of her influence, her works live on today due to a resurgence of interest in her work in the late 20th century. This newfound interest in her works would lead to several collections being published posthumously, including Mule Bone, Spunk: The Selected Stories (1985), The Complete Stories (1995), and Every Tongue Got to Confess (2001), a collection of folktales from the American South.

The Library of America recognized her role in the Harlem Renaissance, in 1995 they published a two-volume set of her work. Even in recent years her work continues to circulate when Baracoon was published as late as 2018. While the story was originally written and completed in 1931, publishers at the time rejected the work die to its use of vernacular, a trait which only makes the work more raw, showcasing itself as a rich piece of history.

While Hurston never received the funds for her efforts, she continued to write books that would ultimately become valuable pieces of history. Hurston’s spirit, themes of race, gender, and identity, and her efforts to preserve and celebrate African American folklore and traditions make her a true embodiment of the Harlem Renaissance.

To learn more about Zora Neale Hurston’s works, find her books here.

Comments are closed.