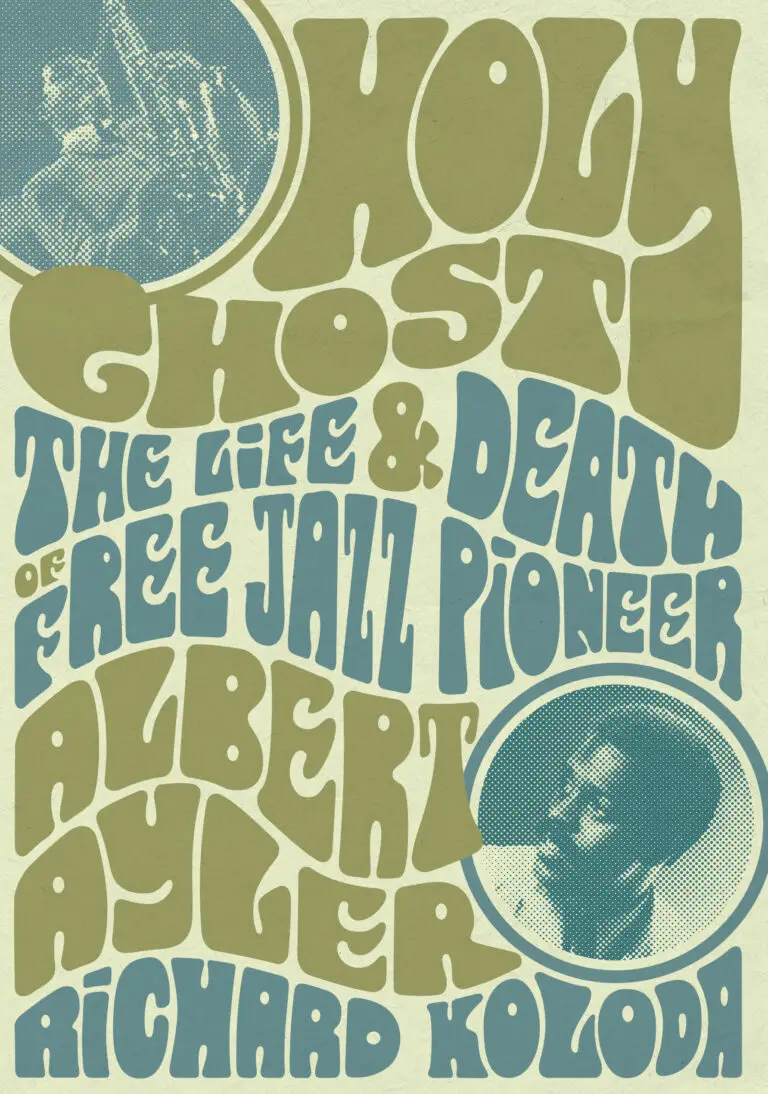

No one in the world of jazz begat more violent debate and unsubstantiated myths than Albert Ayler. Now the works and life of this fearless musician are being re-told and reassessed in Holy Ghost: The Life & Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler (Jawbone Press), a compact yet comprehensive and impeccably researched biography from Richard Koloda.

A lawyer by trade and jazz musicologist by passion, Koloda spent over two decades researching Holy Ghost. It follows Ayler from his native Cleveland to France, where he received his greatest acclaim, to his mysterious death by drowning in the East River in November 1970.

Ayler synthesized children’s songs, the French national anthem “La Marseillaise,” American march music, funeral dirges and gospel tunes into uniquely powerful, sprawling and squalling free jazz improvisations. His overblown tenor honking and high-register squealing made some critics consider him a charlatan or simply insane. Others considered him a genius. One such man was John Coltrane who tirelessly championed Ayler to other musicians, critics and record label heads. Indeed, ‘Trane thought enough of Ayler to request he play at his funeral, alongside that other titan of free jazz, Ornette Coleman.

It was his aspiring songwriter dad who set Albert on the musical path, forcing him to practice hours a day and attend the Cleveland Academy of Music beginning at age 10. By the early ‘50s, he was gaining experience playing with artists like blues harmonica wizard Little Walter. His time in the Army would bring him to France in the latter ‘50s, where he saw Coltrane and Miles at the Paris Olympia and developed an unexpected love for French military music, including the national anthem “La Marseilles” which he quoted in his classic “Spirits Rejoice,” while playing in the 76th U.S. Army Band in Orleans.

His breakthrough, and perhaps his best times overall, would come in Europe, firstly in Scandinavia. Here he would meet and come to play with likeminded explorers like pianist Cecil Taylor and trumpeter Don Cherry and cut his first albums including My Name in Albert Ayler which contained his freewheeling interpretation of the classic “Summertime.”

By 1963, he was in New York City serving up music that was “playing pyramids and geometric shapes” while attired in a green leather suit, Cossack hat and slippers. His meeting with ESP-Disk head Bernard Stollman would lead to his best documented year of recording in 1964, one capped by “Spiritual Unity,” the classic trio disc with drummer Sunny Murray and bassist Gary Peacock, and the skronk-heavy film soundtrack, “New York Eye and Ear Control.” Even with growing press attention, New York City clubs were hesitant about booking this “New Thing” and Albert would head back to Scandinavia to record albums like The Hilversum Sessions and Ghosts.

In 1965, he returned to New York to lead a fierce quintet now featuring his younger brother Donald on trumpet. Albums like “Bells” and “Spirits Rejoice” continued to divide critics. Albert was labeled “further out than Coltrane” by Time Magazine and “a bizarre artifact, not art” by Downbeat. With Coltrane’s championing, he moved from the tiny ESP-Disk to the larger ABC Impulse! label. He went on to wax even more fierce and outré discs like “Live in Greenwich Village,” one that captured performances at The Village Gate and Village Vanguard. This album contains one of my favorite Ayler pieces, “Angels,” a duet featuring a kind of silent movie-styled accompaniment by pianist/harpsichordist Cal Cobbs to Albert’s balladeering tenor.

The last chapter of Ayler’s recorded life was perplexing, when he was moved to create a sort of accessible rock/R&B with vocals featuring “hippy dippy” lyrics by his new girlfriend Mary Parks. Love Cry and New Grass were albums that made no one happy, least of all Ayler, who blamed the commercial move on his producer at Impulse!, Bob Thiele. Albert would have one final victory when he took a turn back to his freer self in a July 1970 performance at the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, something captured on a duo of fantastic 1971 albums.

With his return to New York City in fall 1970, his depression deepened as did his tenuous grasp on reality. There was increased talk about UFOs and spiritual visions, something that had been in the mix since his childhood. He would disappear on November 5 and be found 20 days later floating in the East River. Some said it was a hit for messing with a mobster’s woman or a drug deal gone wrong. One stubborn myth said he was found chained to a juke box. But Koloda works to put these long-held fallacies to rest. He concludes that the depressed 34-year-old jazz man most likely jumped from a ferry near the Statue of Liberty. This was in part due to the guilt of firing his brother from his band and the ceaseless financial pressures and criticism caused by a high-profile/low-profit life on the tip of the free jazz spear.

In his 20 years of research, Koloda has become the world’s foremost authority on all things Albert Ayler. He was a contributor to the critically-acclaimed documentary, My Name Is Albert Ayler, and a consultant on Revenant Records’ ten-CD retrospective of Ayler, Holy Ghost: Rare and Unissued Recordings (1962–70), which has been called “the Sistine Chapel of box sets.” His book includes quotes from his and others interviews with many of Albert’s closest collaborators, most notably from the writer’s long friendship with Albert’s brother Donald. There’s also a carefully balanced array of quotes from critics that demonstrate the reaction to Ayler throughout all the chapters of his short but action-packed recording and performing career. the book concludes with a pained portrait of the post-musical years of Donald Ayler, with his frequent hospitalizations for mental problems and fits and starts at reviving his career.

I had a decent knowledge of Ayler before reading Koloda’s Holy Ghost. But like any great touchstone musician biog, it set me off on a few weeks of very deep listening to the many well-trod and obscure corners of Ayler’s discography. In this way, Koloda has done a great service to both Ayler and every music lover with the curiosity to open up a pathway into this uniquely deep and spiritual canon of jazz.

Comments are closed.