Westward expansion. An 80+ year stretch marked by hope, oppression, sorrow, and death. For Ian McCuen, it serves as a provocative metaphor for a life of disappointment and a world of heartbreak on their fifth album, November’s Westward to Nowhere.

It’s not the first record inspired by grief and the idea of travel. Modest Mouse did the same thing twice in the 90s to massive acclaim. What sets the Buffalo indie folk musician’s concept album apart though is its consistent and clear narrative, which progresses towards its natural finish by the end of the project’s behemoth 18-track, 80 minute run.

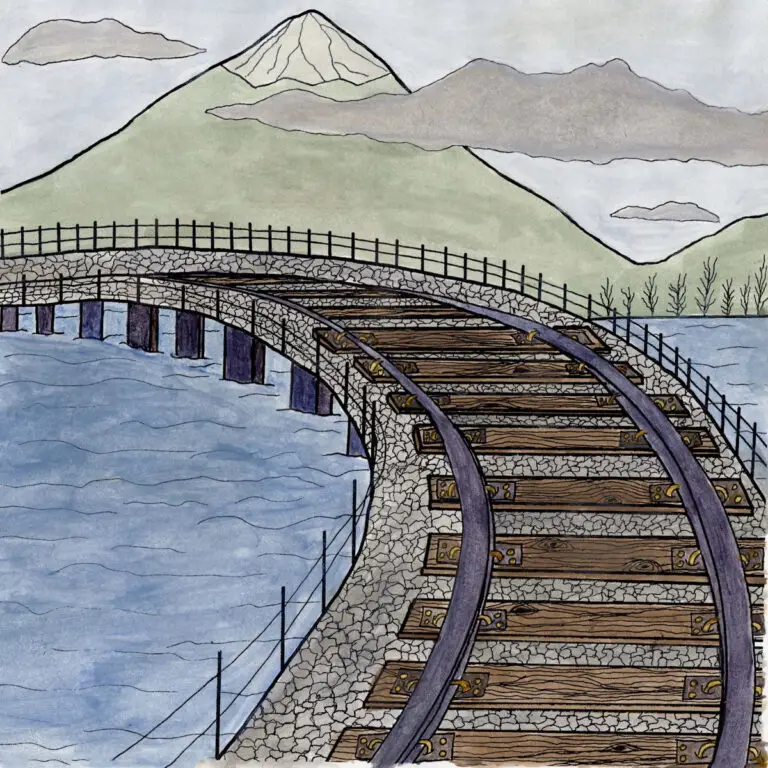

The early going of Westward to Nowhere depicts McCuen’s character as a damaged and traumatized young adult who anticipates and hopes for better things with a change of scene. The lo-fi acoustic opener “Westward” introduces the album’s historical symbolism with the noises of a train and the repeated closing line “westward home, westward home, and I know that I must go,” a phrase which is made a motif via the three interludes found across the record.

Follow-up track “Independence, MO” is a fuzzy but light indie rock song about the “thrill of anticipation” for starting new, coming before lead single “Lonesome Homesteader” (or “Lonesome Dreamer” according to the album listing), a gloomy acoustic ballad spaced out by stretches of organ and banjo. “I walk for miles at a time, daydreaming of a place that’s always mine,” McCuen sings on “Lonesome Dreamer.

This continues onto the waltzy “California Bound,” where McCuen analogizes seasonal change with grief and recovery, hoping that change of scenery will “wash away past trauma.” The same goes for the synth and violin-laden “Beatrice, NE,” where McCuen dreams of traversing the Great Plains and scaling the Rockies. “Goodbye Beatrice, so much world left to see,” they sing on one of several tracks that personally address the pinpointed location on McCuen’s journey.

Musically, Westward to Nowhere is highly consistent and consistently melodic. McCuen’s near whispered falsetto heavily reminisces of Elliott Smith, with their low-key acoustic approach and sentimental subject matter also ringing true of the legendary singer-songwriter. This tonal steadiness doesn’t mean a lack of variety in texture or instrumentation though, with McCuen’s parts on guitar, piano, organ and more being complemented by guest musicians such as Lissa Reed on cello and Sally Schaefer on violin. Reverb-heavy moments of guitar noise add contrast to long stretches of acoustic subtlety on songs such as “American Retreat.” There’s “The Plea,” which closes its six minute runtime with a biting and bluesy guitar solo and hints of trombone. All makes for an experience which sonically conveys McCuen’s sorrow in an affecting and musically accessible fashion.

While primarily personal, Westward to Nowhere has its political moments too, “The Plea” being explicitly so. “Can’t you hear the chanting, ‘no justice no peace,’ how much fucking longer we gonna let Kansas bleed,” McCuen asks on the final verse’s closing line.

There’s also the on-the-nose “Running Still (Worker’s Hymn),” a mostly acapella anthem where they sing in the first person about working class strife with exploitation, and the heartful late-placement ballad “American Retreat” which addresses Native American genocide, abandonment of military veterans, and general lies from “the lofty speak of what an infinite frontier provides.”

Such cynicism defines the rather hopeless back half of Westward to Nowhere. There’s “Letter,” on which Ian McCuen pens letters to a sister, an old friend, and a former lover, detailing fun reminiscence, regret, but most of all, agonizing over the distance created from these loved ones. “I can hardly recognize where I’m heading or from where I came,” they observe over the light drumming of the song’s chorus. “On my shoulders lays the blame.”

McCuen’s journey away from misery has made life even more hopeless, something fully emphasized in the album’s final three tracks. There’s the upbeat organ/violin-driven “Lonesome Drunkard” with its alcoholism play-by-play, followed by the overpowering gloom of nine-minute “Deadwood, SD,” which takes their sadness to suicidal levels.

McCuen forecasts themselves as “face first in the dirt with a bullet in the brain” and “just another number in the morgue,” and reminds of the album’s historical symbolism by alluding to “repeated failed attempts at finally striking gold. In the last few minutes, over a subtly building assembly of piano, guitar, , McCuen echoes frustration with a disgustingly wrong promise, singing “I’m so fucking sick and tired of hearing ‘Westward Home,’ after all this time I still don’t know where the hell I belong.”

No point is more bleak though than the closing track “Nowhere.” The train from the end of “Westward” returns, not to take McCuen on a life changing journey, but to take them out. “My brain and my body have given out on me, so I’m giving in to let these tracks take me,” they sing after two minutes of desolated acoustic guitar playing. McCuen’s echoey vocals and the track’s eerily sparse musical framing make this a haunting self-eulogy, as they talk about an eradicated sense of youthful optimism, reflect on a life of unfulfilled self, and envision a memorial not consisting of any heartfelt tributes, but “just regret for my days.”

Westward to Nowhere begins with a clear point and ends on a resounding personal message: the grass isn’t always greener elsewhere. Change of scene and change of personal direction don’t always lead away from misery. It may lead nowhere, and it might make life more isolating than ever imaginable. Originally aiming for California, McCuen never got farther west than Montana, a testament to the fleeting nature of personally prophesied destinations.

The album bears similarities to 1984 hardcore classic Zen Arcade by Husker Dü, a concept record about a boy who leaves a troubled home to find a world of nothing but. Ian McCuen never comes close to being as loud as Husker Dü, but the emotional ideas and big picture thinking are all there.

This is a long record that doesn’t do anything musically shocking, but within the album’s historical approach, it’s all fitting. Continental travel is long, consistent, and miserable, often like life. On Westward to Nowhere though, Ian McCuen conveys this in a way that ends up being pretty enjoyable to listen to.

Key Tracks: “Independence, MO,” “California Bound,” “American Retreat,” “Deadwood, SD,” “Nowhere”

Comments are closed.