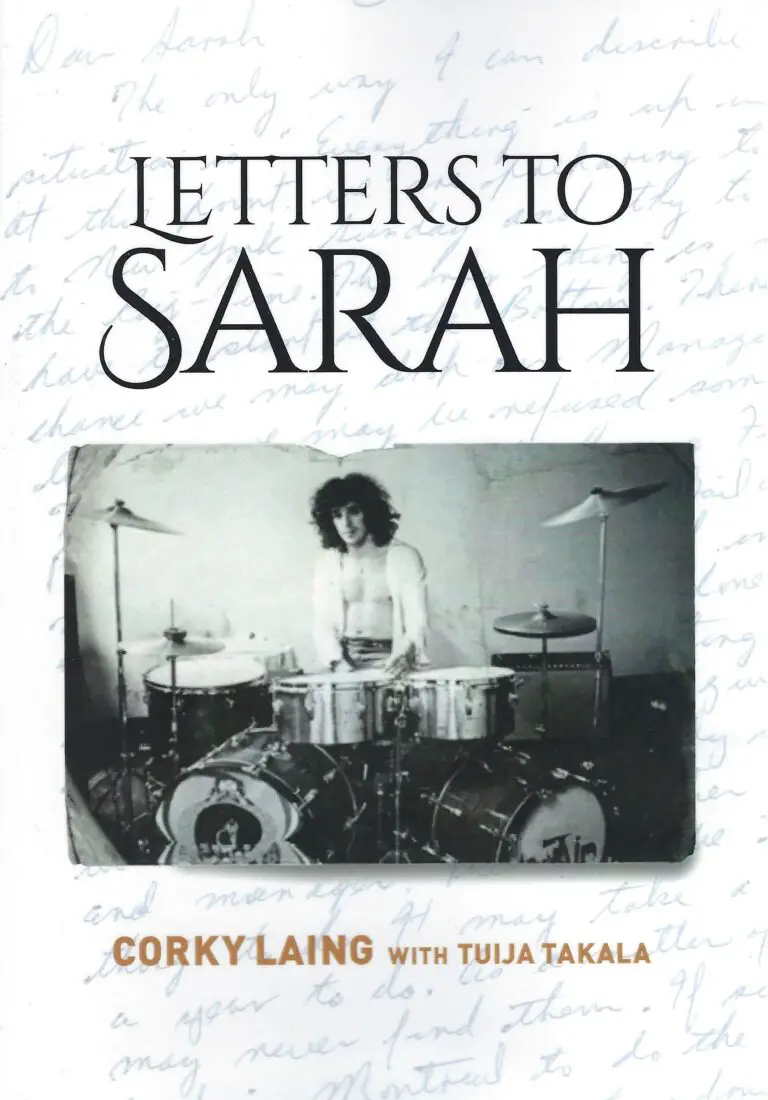

What’s the most eardrum pummeling cowbell moment in rock? Thanks to that famous Saturday Night Live sketch, you might think it’s Blue Oyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper.” But for my money, it’s the cowbell count-off pounded out by Corky Laing in the rock classic whose saucy lyrics he also penned: Mountain’s “Mississippi Queen.” The tale of how that song came to be and many more hilarious and harrowing anecdotes from his long and winding career are told in his eminently readable memoir, Letters to Sarah.

Co-written with longtime manager and partner Tuija Takala, Letters to Sarah is a rock autobiography with a difference. In addition to Corky’s exceptionally honest recollections of his highs and lows, there are excerpts from the dozens of letters that he wrote to his mom, Sarah, between 1963 and her death in 1998. These were a way for Corky to keep in touch with his family and try to make sense of his life, while he was away furiously touring and recording for years on end.

Raised with triplet brothers and a sister in Montreal, the sports-loving Laing would first become enamored with the drums when he saw the hyperbolic jazz great Gene Krupa, on TV. Laing would then forsake his and every Canadian’s first love, hockey, for music because, as he quips, “the drums don’t hit back!” His first public performance was an impromptu one backing the famous vocal group, The Ink Spots. In short order, he would be engaged in regular gigs and drum battles, just like his idol Krupa.

Embed from Getty ImagesIn 1965 at age 17, he and his band, B+3, would be in New York playing at the famed Peppermint Lounge. At another gig around that time in the Hamptons, he became acquainted with his guitar partner-to-be in Mountain, Leslie West, then playing in The Vagrants. Summer residencies in Nantucket over the next couple of years brought him into contact with a crew of writers who would inspire his interest in literature. Nantucket is where he would come up with the gem, “Mississippi Queen.” Forced to take a long drum-solo during a power outage at a gig and witnessed the seductive dancing of a friend’s Southern-bred girlfriend. Laing’s passion made him start singing what would become the opening lines of his most famous tune – “Mississippi Queen, you know what I mean?”

When he returned to Canada, he got to know luminaries like The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Cream and The Who since his band opened for them at venues like the Montreal Forum. By 1969, his band evolved to a more progressive sound and was renamed, Energy. During another opening slot, he got to know Miles Davis’ great drummer Tony Williams, someone who would later refer him to Jack Bruce that

would put another milestone band on his resume.

Corky and Energy came into the orbit of Felix Pappalardi (the producer of Cream and bassist, founder and producer of Mountain) while playing at the World’s Fair, Expo ‘67 in Montreal. Felix was interested in producing the band and especially intrigued by Corky’s drumming and lyrical input. After Mountain’s debut at Woodstock, Pappalardi lured Laing away from Energy to join what was to become one of the hardest working (and partying) proto-metal bands.

As for “Mississippi Queen,” Laing says he copped the groove from Levon Helm’s playing on The Band’s “Up on Cripple Creek,” a man he would become very close to during many visits to Woodstock to record at Levon’s legendary farm studio. When Laing was trying to come up with a good Southern town to name check in the lyrics, a friend suggested “Vicksburg” and Corky awarded him 10% of the publishing for the two syllables. The first person to hear “The Queen” outside of the band was Jimi Hendrix, who was working in an adjacent room at The Record Plant at the time of its recording. Interestingly, Laing would go on to earn a Gold Record for his contributions to the Woodstock ‘69 soundtrack, not with Mountain (N.D. Smart was Mountain’s drummer at that gig), but for Ten Years After’s “I’m Going Home.” It seems Laing was enlisted to overdub drums while at the Record Plant with Mountain because the drum mics were not working during the live recording of that particular song during TYA’s Woodstock set.

The book has plenty of sex and drugs along with the rock-n-roll, something that, along with bad management, spelled the end to Mountain’s initial frenzied three-year run. After much promise, his next band, the super group West, Bruce & Laing, would also collapse after a brief two-album run, due largely to overindulgence. Laing also spends a good deal of time speaking of the brilliance and flaws of Pappalardi and his creative partnership with his wife, Gail Collins. Collins would contribute lyrics and album art to Mountain, but ultimately go on to shot and kill the bass player with a gun he bought her in the early 1980s.

Corky would next hook up with the likes of Ian Hunter, Mick Ronson, Lee Michaels and Todd Rundgren to make a couple of albums in the singer-songwriter vein, music that was “very Springsteen” in his words, with only the first earning a release. He would go on to be a part of the legendary Lone Star Café scene in New York City backing the hilarious Texas bad boy singer turned novelist Kinky Friedman, who contributed the introduction to Laing’s memoir. For a while, Corky would cut his hair and join a promising new wave band, “The Mix.” Through a chance encounter on the beach near his Connecticut home with jazz guitarist Larry Coryell, he would be introduced to Buddhism. This would go a long way towards vanishing his demons. Laing’s up and down life would settle for a time when he accepted a job in music publishing with Warner-Chappell Music. He would then move on to even more success, and a “six figure salary,” as Vice President of A&R for Polygram Canada during the MTV era, until a merger put him back in the playing business.

Embed from Getty Images

Laing would finally get to play Woodstock in 1994. This was at the smaller Woodstock Reunion Concert at the original concert site, versus the grander Michael Laing-produced affair in Saugerties. At this gig, the Mountain lineup was West and former Hendrix bassist Noel Redding. This book and this chapter of Laing’s life comes to close with the passing of his mother in 1998, when he is back making music with Redding and a new guitarist, the Spin Doctors’ Eric Schenkman.

As a musician, Laing was an indispensable ingredient in the success of Mountain, a band that paved the way for the metal we know today. He had a uniquely powerful style that drove the straight-ahead rock numbers like “Never in My Life” and “You Can’t Get Away.” It was one that matched the fuzz-leaden bass of Pappalardi and Leslie West’s searing blues run and thick power chording. He also had an unflagging stamina and an improviser’s heart. It was Corky’s pulse and dynamics which led the band through long extrapolations on classics like “Dreams of Milk & Honey,” from their album Flowers of Evil, and their unique version of “Stormy Monday,” captured on live album from the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival.

I saw Mountain several times during their early ‘70s glory days and my ribs are still quaking from Pappalardi’s sub-atomic bass and Laing’s double bass drum and cowbell combo. The last time I saw them was on August 11, 2001. It was at a free lunchtime concert in the plaza at World Trade Center so I couldn’t pass it up. My taste in music had certainly changed since the early ‘70s but, damn the hipsters

and those who worship at the altar of Pitchfork, I still kind of loved Mountain. It was a beautiful day and band played energetically to a happy crowd of old and new fans. I even caught one of the drumsticks hurled by Laing into the crowd. Thirty days later, that stage would be the site of something very different – the smoldering wreckage from 9/11

terror attack.

Comments are closed.