It has been over fifty years since the Woodstock Music & Art Festival made its mark in history from August 15-18, 1969 in Bethel, NY, and one year since the festival marked its golden anniversary. The Museum at Bethel Woods displayed a special exhibit throughout the year of Woodstock photographs and artifacts and hosted a weekend of music in their pavilion and throughout their grounds where the historic festival was held.

Throughout that weekend in 2019, Bethel Woods had a meeting spot for 1969 festival attendees at the top of the hill where the original festival was held. There, I was introduced to Lisa Law who, upon noticing my camera, was quick to say, “Here, do you want to take my picture?” We only had a brief introduction at that time with all the hustle and bustle of the festivities that day

Lisa Law is an accomplished photographer and videographer who considers herself to be a historian/documentarian with her camera, capturing candid moments as they happen. In the last five decades she has shot iconic portraits of now legendary musicians (sometimes at major moments in music history) and documented social/cultural changes and the lives and society of indigenous people, through both still and video photography. Her documentary film and book by the same name, Flashing On The Sixties, features her images and videos from that era. More than 200 of her images are also on exhibit in the Smithsonian Museum.

As a member of the Hog Farm Commune (which included Wavy Gravy), she was part of the group flown from Los Angeles to New York to provide the “security” for Woodstock. At the festival, Law was responsible for setting up the Hog Farm kitchen and getting food ready for the festival-goers who wanted it. Even with all of this, she managed to weave in her photography and videography to capture the arrival of the crowds and other scenes at the festival.

Shortly after the conclusion of the 50th anniversary weekend at Bethel Woods, I caught up with Lisa in the Town of Woodstock to hear more of her story. Starting with her early days with a camera, she brings us through her experiences behind the lens over the years, including recent works with establishing a museum in Yelapa, Mexico. Her experience at Woodstock is only a portion of a much greater story.

Steve Malinski: What drew you to photography? What got you into picking up a camera for the first time?

Lisa Law: Well, my father was a 16 millimeter [film] man. He used to make movies of wild boar hunts in Mexico, fishing in Guaymas, the garment industry demonstrations in North Hollywood. So, he was always making movies on 16 millimeter. Besides being a furrier and father of three, he joined the Navy in the second world war. He gave me a little Brownie when I was probably six and I’d go around shooting, you know, kids follow what their parents do. So, I would go around shooting my girlfriends and swimming in the swimming pool. I love horses. I was a horse person – I had my horse in the backyard and a swimming pool in the backyard. I used to go riding at Griffith Park.Griffith Park is where the Greek Theater is. There’s a mountain there. And you have to go around like this to get to the valley. Laurel Canyon is up on top. Mulholland’s on top, and Topanga goes over.

So, the thing about me is that I was always a person who kept their negatives. A lot of people don’t keep their negatives, so I have all the negatives of everything I ever shot. So I was shooting my life story with this little Brownie, and then at the age 15 I moved to San Francisco to live with my aunt. I shot everything there too. And then I went to the College of Marin and I started working for the manager of the Kingston Trio. He was a photographer and gave me a Honeywell Pentax.

I took two classes one in City College in San Francisco and one in College of Marin in portraiture. That’s when I learned to really crop in the camera. Whereas before I didn’t know how to do that, but I was already good at shooting what I was interested in. And I am instantaneous. When I shoot, I see something and I shoot. A lot of photographers wait, la la la, say “smile,” all this stuff, right? I wasn’t like that, I just shot immediately. For example, so I just shot a conversation I had earlier today. She didn’t see me doing it.

I started shooting for Frank Werber, Kingston Trio, Sons of Chaplin, [history trend] and I got some backstage passes to The Beatles. And I shot Sonny and Cher backstage. I went to the Cow Palace, saw The Beatles. And I shot Peter Paul and Mary at a concert and that’s how I ran into their road manager [Tom Law] and ended up marrying him. So we knew everybody on the West Coast and the East Coast in the music business, basically because there weren’t too many people at that point. And so I was shooting Peter, Paul and Mary. And then when I was working for Frank Werber over in Sausalito, there was the Trident Restaurant. It had mostly jazz on the weekends at night.

Well, I heard this other group in Berkeley, called Brazil 65. And I said, “Frank, you gotta get this group. They’re fantastic. And it would be good on a Sunday afternoon. Over on the deck your restaurant on the water there on Sausalito.” And because Sausalito is very popular town, a lot of tourists go there and shop and boat and sailing and everything. So he said, “No, no, no.” And I said “come on you just trust me.” So that’s where the Brazil 65 got their name, basically was playing at the Trident. That’s when they became popular – Sérgio Mendes. Bill Evans played there. You know, it was really great. So I was shooting all the music I could possibly shoot and because I met Tom Law at the Peter Paul and Mary concert and Berkeley, I then moved down to LA. And he had bought a castle with his brother {John Philip Law, the actor] in the Los Feliz area [in LA].

Bob Dylan… because Albert Grossman was Bob Dylan’s manager… He knew Bob and Bob wanted come out to LA to hang out for a while and he rented some rooms from Tom in this castle. And that’s when I shot my famous pictures of Bob at The Castle, because he was staying there and I was living there and he would sit down at the dining room table I would just keep my camera out, start shooting.

The Velvet Underground stayed at the house too, Lou Reed. Andy Warhol came over, I shot them at The Trip. And my pictures are used more than anybody’s from that gig.

Andy Warhol did his screen tests (I guess they’re called) of these people that hung out at the factory with him and he projected them behind the Velvet Underground. So as you’re watching Lou Reed play with his band you’re seeing these videos of the same people, but it was like a screen test projected from the back. As the concerts happening, you’re seeing the projection of Andy Warhol’s screen tests. But other people photographed it too. But they strobed [flashed] it. And because I was then shooting with a Nikon and a fixed lens I was able to get really sharp shots with the projected images of the same people playing doing their screen tests behind, and I was very artistic, was the only time that Andy Warhol did that type of projection behind the group. It was called Andy Warhol and The Velvet Underground, and they only played three nights, and I shot them the first night because they were staying in Tom’s house.

Well, those pictures, if you look at all the books on the Velvet Underground, those are the pictures they used because I was the only one shooting at that time, that was shooting really good pictures. The other people were strobing which just gave a white background.

SM: When you’re in these close settings with Bob Dylan and Lou Reed, did you ever get a sense of shyness or intimidation when you’re taking pictures of them?

LL: Well, Bob kind of made me feel kind of weird. He wasn’t that…friendly? We were friends, but I was his masseuse and cook too. But I’d be sitting there and I have my camera shooting away and he’s sitting there and once in a while, he’d like make a face or something.

So, I was shooting as much as I possibly could. But I probably could have shot more. And I didn’t say, “Okay, stand there I’m going to take your portrait.” I just shot whatever was happening. That’s what I’m known for, is shooting at the moment that something’s happening. But that’s setting up a shot. I take group shots now. I’ll take whole group shots of bands, then I’ll set them all up. And I’ll shoot families and get everybody together. When I was shooting for my book Flashing on the Sixties, most of those pictures are very candid shots. Like Cher backstage at the Cow Palace with Sonny. David Crosby getting ready to go on that same event at the Cow Palace. I shot the Byrds at Hollywood High School in concert. I shot John Lennon running behind the stage with his guitar when the girls are chasing him. And when Dylan was staying at The Castle with us, we went down to the Whiskey a Go Go and saw Otis Redding.

When I was sitting at a table with Bob Dylan, Tom, and a bunch of friends, I just jumped up and went up to the stage and started shooting. Well, Otis was bouncing all over the place. Half the pictures were out of focus because it was too dark. But I was able to get like three or four really good ones. Those were then used by Atlantic Records as his promo shot and album cover after he died.

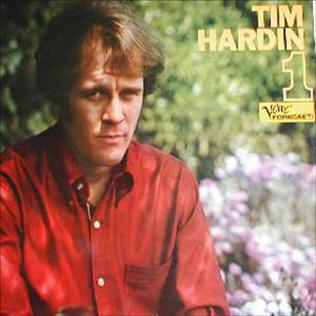

So with Tim Hardin, I shot his first cover and last cover. I shot him behind The Castle in the garden. Then he went to Verve Records, he said he need an album cover. So I went to Verve, and they used it. So I knew how to get to Capitol Records and how to get to Verve Records and Atlantic Records and they used them as their promo shots or album covers.

After we moved to Mexico and then back to LA, we went to the Haight Ashbury. So I documented the Haight Ashbury, the human being atmosphere. The Streets of the Haight. Monterey Pop….at Monterey Pop I had a little puppy that I had to feed with a bottle because the mother couldn’t be him. So I missed out shooting Otis Redding and Janis Joplin because I’m holding this baby puppy. I never considered myself a photographer. So, it didn’t matter, just took care of the little puppy dog.

SM: So at that point was photography just a hobby for you? At what point did it to turn into more of a career over hobby?

LL: It was after I divorced my husband in 1978. So all the way up to 1978, even Monterey Pop….that was just documenting my life. I’m very good at documenting my life.

So when I moved to New Mexico, and I’d started shooting the Hog Farm and Ken Kesey and the buses. Then I would print them up and leave them in their office and I was getting to be known as a historian.

When we went to Woodstock…Of course, I shot us getting on the plane [in LA], waiting in the airport, putting the tee pee poles and tee pee on the plane. I didn’t shoot in the plane, which is weird. And it’s probably because I had my two-year-old with me and she was sitting on my lap and I probably didn’t do it because of that. I didn’t shoot one picture inside that plane. But when we got off the plane, as soon as we came around the corner from where you get off… all these cameras were there. And the lights, cameras, rolling and rolling! They sent a jumbo jet to pick us up, empty. Who does that? Do you know how much that costs?

SM: Let’s see, in 1969 dollars….

LL: Expensive. But the airline probably donated it. So the press, they said, “Ah, we hear you’re the security.” Wavy [Gravy] says, “Well, do you feel secure? Yes? Well then it must be working.” “What are you going to use for riot control?” “Seltzer bottles and lemon pies!” So we then got on buses, and we went to the site and the last picture on that first roll [of film] was of my husband putting up the tee pee. So that was the last black and white then I changed to slides (Kodachrome).

But also when I went into town to get the food, I got a camera and some film, and I shot Super 8 . Because I shot Super 8, I was able to document behind the scenes. The same way I document with a still camera, but now with a movie. Because of that all my footage is being used now in every single one of those documentaries you’re seeing on TV, they know who to come to. And a new one that just came out from by Bohemian Films, The Festival That Rocked the World is the new one that just came out and not the American Experience from PBS. It’s a whole other one. It’s I think the best one. It has footage and vocals and stuff like that have never been seen before. It’s got a lot of my footage and me talking about everything. Because I have so much information about the Hog Farm and everything and I’m so talkative. They really liked it, liked working with me. I’ve gotten used to doing it. Before I couldn’t even speak – when my when my book came out and they interviewed me on the radio and I could barely speak.

SM: When you were actually at Woodstock, you were running one of the kitchens?

LL: Yes, there was only one kitchen, basically. Our kitchen, the Hog Farm kitchen. There were two but one of them was for serving us while we are setting up everything and the other one was for serving the crowds. I helped design that one, the kitchen and the five food booths that had 10 lines. So, I went and got $3,000 from John Morris and while I was shopping, they were building the kitchen and the serving booths. When I got back they were just finishing that.

So as soon as we got our pots out of the boxes, we started cooking. And I went and took a flatbed truck and went to a farm next door and I said, “I’ll take this row, that row, and that row.” Now that footage of me saying that was filmed by the [Bethel Woods] museum, they did an interview with me. So they used that footage of me saying that in one of their exhibits. When I went to see it recently, I leaned back in the beanbag and then I would talk and the other people around me. They would go “what?” and I’d say, “Well, that’s me over there! That’s me over there!” “That’s you?!” they’d respond. And I would narrate it for them. They liked it. So anyway, that’s what I did. I went and got all the vegetables from farmers locally. And it was August so they had a lot of it. So we’re cooking bulgur wheat and then I bring all that food and then the volunteers would chop it up, stick it in the pot to cook. And so people were waiting in that line. If you were hungry, you could eat. You did never go hungry at Woodstock.

SM: Even with a crowd that large?

LL: I had half the food leftover.

We were cooking non-stop, and people were in line. There were 25 to 30 people per line and there were 10 lines and it was just going: serving, serving, cooking, serving, serving. I bought 160,000 paper plates. I kind of knew what was gonna happen and when I went to town I got another three thousand. I spent $6,000 of their money to buy the stainless steel pots, to buy the cleavers, to buy the trash cans to mix the muesli in. To this day I still have the two cleavers and the stainless steel pot. One’s at my daughter’s show in Santa Fe. She’s got an exhibit up right now. She did a whole thing called “Hail Hail Rock and Roll: Happy 50th Woodstock!”

SM: Was the scene when you arrived at Yasgur’s Farm after travelling up from JFK different than what you expected?

LL: Well, when I got there they were already serving 100 people. The first group arrived by bus and they already set up a kitchen with plywood and two by fours and plastic. This was happening maybe a few weeks before the festival. They were already making the free stage, the little kitchen, and they had brought food with them. And they were they were cooking what they had with them, and [Max] Yasgur had yogurt, milk, eggs. He was selling stuff to us from his farm, and he had brought water and milk trucks over.

And they were fixing a LOT of food. I mean, big plates of food for everybody. Because they were being fed, everybody helped. We needed something done, we’d put them to work. Because otherwise I’m not gonna sit around doing nothing. They all helped. So we had different groups that came in and helped. And then the [crowds] started arriving and I had looked around and I said, “You know, this is gonna be bigger than we think it is.”

And that’s when I went to town and I spent that money. When I went in to get the money from John Morris, I said, “These people are going to starve if we don’t feed ’em.” And the concessions that were up on the hill? Those pointed roof ones… They were out of food the first day. There was no way to get more food because there was no way to get anywhere.

It was solid people and solid cars. And in my footage I stood right in the middle of them coming in. I just stood right there. And today I still shoot that kind of shot during parades and marches. I just stand [still]. And they walk around me. And you can see their faces and chanting in their signs and I shoot demonstrations like that.

SM: How did you find the time to take all of the photos and footage in between making sure the kitchen was up and running?

LL: Because I shoot on the run, I’m always shooting. Like I just finished visiting today and I’ve already shot 100 pictures; I should actually shoot you, too. And I shot at lunch today and shot portraits without even anybody really knowing I was doing it, that’s how I get away with murder. Unfortunately, you know, these ones aren’t as sharp, they’re in focus but they’re just not – they’re pixelated more with the phone. I hope [these cameras] get better. And then next i-Camera. I should be shooting with a camera. But I like to be more candid. If you have a full camera, it’s more intimidating than a phone.

SM: That’s my problem when taking photos. Everyone sees you with this big camera and they’re suddenly aware of your presence and their expression goes from candid to… not natural.

LL: Right. So I was shooting at the Woodstock event at the museum [Arlo Guthrie] and I was sitting there and I turned around and the sun was still shining. And all these kids are dancing like crazy and I get to snap them because that’s where the action is. It’s these people happy, dancing, celebrating. So I think probably I’ve shot over 1,000 pictures the last three days [at the 50th anniversary] and a bunch of the people came to my exhibit [at The Stray Cat].

SM: What was the lasting effect of Woodstock? Did it change your perspective on photography or have a major impact on your life?

LL: Well, what it did show me is that I have to shoot more because I looked at other people’s photographs that were up in the museum – all of those photographers and their best pictures from Woodstock. There are pictures in there of the food booths up on top of the hill and in front of the stage. When I was shooting the movie, I wasn’t shooting much of the stills. So when I consider it, I did a horrible job of shooting my stuff. But I did get some. If you look at my show, you will you will see some good pictures of Wavy coming in and the aerial shots [from a helicopter] and cooking shots and stuff like that. I could have shot 10 times as much. But I didn’t. I did get the movie, which is being used a lot by every single documentary filmmaker. They’re using it, but I didn’t shoot enough stills. And if I was really smart, I would have gotten a bigger camera and really shot the heck out of this year’s anniversary. But I figured that, at 76, do I need to take all those pictures? Because I’m still sitting in my office with thousands of pictures that nobody’s ever seen. So you have to think about that. Do you just keep shooting? Or do you slow down a little bit? Now, I also have Woodstock Three [1999] – and Two [1994] – nobody’s ever seen my Woodstock Three pictures. I’ve documented the heck out of Woodstock Three, for People magazine. I have an entire shop of Woodstock Three, never been seen. So I have all these rooms, slides, and proof sheets, pictures that nobody’s ever seen before. And so that makes me feel bad that I want to share everything that I’ve taken. That’s why I take pictures, it’s for sharing. That’s why people look at pictures. It’s because they want to see what you saw, what happened. And it’s very important – photographer’s work is very, very important because you could tell somebody about what happened but you can’t really describe it unless you show them an image. A photograph is worth 1,000 words, right? So I feel that I owe it to society to be able to share that.

About four years ago, I did a show in Yelapa, Mexico. I didn’t want to bring it home because it belongs down there. So I built a museum to house the pictures. [El Museo de Historia at Arte y Cultura de Yelapa]

There was an old building that used to have a sheriff’s office. We fixed up the sheriff’s office, we fixed up the plaza and we built the museum. I have 108 pictures on the walls. It took five months to build. I was the builder. I was the curator. And then I went and got tables full of artifacts, then I had to write up all the wording go with each one of those things. So there we are cutting the ribbon on the opening day, which was my birthday, March 8, [2019], alongside the guy who gave me his crew to build it the woman with the funding, and all my government people. There were a lot of compliments. I wanted to show the people what Yelapa was like back before there was electricity and plumbing.

We spent a lot of time getting the museum ready. Five months, five days a week.

SM: Back to Woodstock, do you think the 50th anniversary weekend was the celebration that everyone kind of hoped for?

LL: For the people that paid for their ticket and got their passes and came all the way up there to do that? They were very happy. And the ones that went over to Gerald’s [nearby gathering], those guys were happy. Okay, but it wasn’t like a Michael Lang thing. And Michael Lang’s things are too big and too corporate; nine never work. [Woodstock] Two and Three did not work. They did not work. Right. Okay. What happened here was very strict over the at the museum, and kind of loose over at Gerald’s. It worked, because there were two different ones. 100,000 people didn’t show up. Maybe 16,000 over at the museum [Bethel Woods] and 200 or so over at Gerald’s.

Well, this was the big 50th anniversary. Well, Michael Lang was invited to that. They gave him a house near Yasgur’s Farm. And he and Henry [Diltz] and and Bill Hanley and all those guys hung out in that house. So Michael Lang got to celebrate Woodstock, even though he couldn’t put on his event. They brought him over to be at their event to celebrate with those people who celebrate Woodstock every year. That was great for Michael Lang.

Comments are closed.