Imagine you’re an aspiring 11-year-old musician and your father tells you, “Devon plays music next door.” Then, that Devon turns out to be Devon Allman, son of Allman Brothers founding member Gregg Allman, and co-founder of the Allman Betts Band. If I was that kid, I would have to change my underwear. But for singer/songwriter Jackson Stokes, it is one of several galvanizing moments in this up and coming rocker’s venture into music.

At the ripe old age of 27, Tyler Jackson Stokes pursuit of music has been dotted with you can’t make this shit up moments, joined by those of honesty, passion, and respect, that has helped to subsidize his development. I spoke with Stokes by phone from his home in St. Louis, MO at the latter end of a self-imposed quarantine after returning from a west coast tour, because, as he puts it, “I shook a lot of hands on the west coast.”

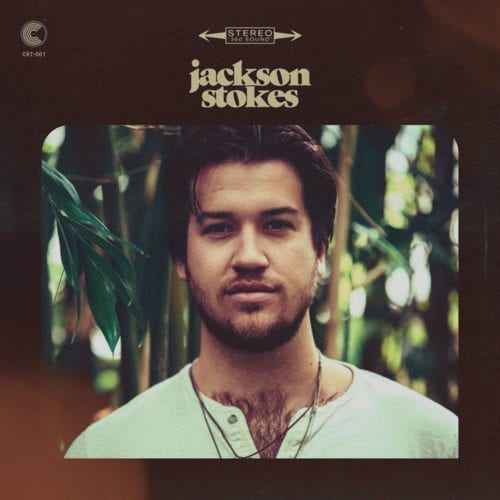

Over the last few years, Jackson has been fortifying his road chops as a member of The Devon Allman Band, The Devon Allman Project, and in 2020, opening for the Allman Betts Band in support of his debut release, Jackson Stokes, out on Create Records, Devon Allman’s new record label.

Knowing how his association with Devon Allman has turned out, I wanted to go back to the beginning when Jackson found out who his next-door neighbor was. I imagined that he started playing his guitar in the garage, door open, amp up to 11, hoping, praying, that Devon would hear it and say, “Who is that? I’ve got to go play with him!” Sharing my hypothesis with Stokes, knowing full well it wasn’t true, he joyously took the moment to set the record straight. “Well that’s not what happened. But, it’s not far from it.”

“It was very organic. My dad, I call him a talk to the neighbor’s guy. Older fashion, knows everyone, help’s everyone out kind of thing, and I was learning and already playing guitar and really passionate about it. My dad has seven Allman Brothers vinyls, and had been an Allman Brother’s fan, but doesn’t get caught up in celebrities. He said, ‘Devon plays music next door. You should go talk to him.’ So, I walked over there. I just had an acoustic guitar and knocked on his door. He opened up and he was like ‘Hello?’ and I was like ‘Hey, I’m Tyler, I’m from next door. I play guitar.’ I remember him saying ‘well play a little bit.’ I played a little bit for him, and he could tell I wasn’t just a kid, I was passionate. He said, ‘that was cool, kid next door plays guitar, I play guitar.’ “

“But the real defining moment; I was playing with my friends and I heard the music coming from their house. I left my friends and said ‘guys, I have to go check this out.’ So I left my friends, and I knocked on their door and Devon opened. ‘Excuse me, Mr. Allman, you mind if I just come watch your rehearsal?’ It was beautiful. You’re 11 and you just don’t really know about social norms. It’s blissful ignorance. He said ‘okay, sit in the corner and shut up.’ So, I sat in the corner. I believe they practiced every Wednesday. From 7 – 9 or 6 – 8. So, I would come home from school, do my homework really quickly, and I would just go over there and watch them work. Watch them rehearse. Watch them talk. Then afterward I would ask questions and Devon and I just became friends.“

“We kept up for five or six years and I finally came up with some songs. I had written songs before and he would say, ‘You’re a promising writer.’ I finally wrote some that were good enough and he was like ‘Hey, I’d love to produce an EP.’ Then from the EP, we did this little five song in Memphis with my old band (Delta Sol Revival) and it went really well. So, he was like ‘I’d like to do a solo record for you and an LP.’ When we started doing it, a job opened up in his band and he said, ‘I’m already producing your record, why don’t you come on the road for 2 years, tour with me, kind of build up a little fan base. Get some sea legs underneath you. Then we’ll release it and you can go back on your own.’ So that’s somehow, exactly how it worked.”

With that, Jackson’s voice takes on a tone of reflection. “When in a big journey, you forget the little steps, and all the things that had to just keep going right. So lately, I have been taking a lot of gratitude inventory. This is an amazing story. I never thought of it that way. It is very unique, and it’s crazy that the universe would catch both of these careers riding it and working alongside each other. I hope that I’ve been able to help Devon’s career, but obviously he has helped my career way more than I’ll know.”

Before ever getting his hands on 6 strings, air guitar was his instrument. Taking center stage in his room for an audience of siblings, he would exhibit his talents via Lynyrd Skynyrd ‘s “Gimme Three Steps,” for them. “I really got into Skynyrd,” he proudly boasts. “My parents took me to a Lynyrd Skynyrd show. It was great. It was like anyone’s first show. I had seen shows, but this was my first show where I was really invested in the band! I knew every song, I was prepared, I was ready to go. Obviously, that experience for anyone’s first invested concert is changing for most of us music people. I came home, and the next day I picked up a guitar.“

With Stokes pursuit of music now in full force, his musical palate matured over his formidable years. He breaks down his genre discoveries by age ranges, similar to pencil marks on a wall, showing how you’ve grown. From ten to thirteen, it was, as he describes it, classic rock. Allman Brothers, Pink Floyd, Zeppelin. Being a mid-westerner, Styx, Super Tramp, & Foreigner are in that mix in for good measure. Blues is the next notch on the wall. Barely a teenager, he could already discern the sacredness of the Blues, while looking to the masters: Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, B.B. King & Albert King (a St. Louis native) to help guide him through his apprenticeship. Mid high school found Jackson taking a deep dive into jazz. Bebop to Big Band and everything in-between. Add sojourns into Soul and Latin music, and you get the depth of Jackson’s musical awareness which has served as architect to his musical evolution.

I hope that I’ve been able to help Devon’s career, but obviously he has helped my career way more than I’ll know.

Jackson Stokes

Post high school, Stokes attended Drury University where he obtained a degree in musical therapy. Not exactly the career path that one takes if the studio and road are to be your life’s calling. I asked about this decision and how he uses it today. While praising the profession, Stokes offered up a disclaimer; “I am a certified music therapist, but I do not practice music therapy. I am not doing music therapy by playing music.”

His time studying music therapy took him down a path that varies from a typical music major. “I worked a lot in Hospice, a lot with kids with autism. A lot of that is patient preferred music. I was playing a lot of music that the people loved. In Hospice, I played a lot of old jazz standards, because there were older people. That really helped me grow in the sense of just playing different styles of music and working with people. The college degree thing was essentially a backup. All my family is creative. My brother is a journalist, my other brother is a filmmaker. My parents were just hoping to God that one of them would go to college to get a back-up career. I did that, and I am blessed I haven’t had to use it.

But let’s not think that school didn’t produce its own rewards. “I didn’t have a normal music school thing,” he asserts. “I got to experience a lot of heavier life things, which I think inspired my life and writing a lot. I wasn’t just sitting in a practice room and going to frat parties. I was working in hospitals or in hospice wards, helping people in harder situations. I feel like it almost escalated some life experiences for me or sped it up. “

“It really helps me with gauging an audience in performing, because you have to adapt very, very quickly when you are a music therapist. You never know what’s going to happen. You’re working with kids with autism, or people with mental disabilities, or people that have triggers. You’ve got to be very cognizant of how their reacting. What I’ve learned specifically is there is a thing called the ISO PRINCIPLE, which means you meet someone where they are and take them where they want to be. If someone has terminal restlessness and they are going crazy at the end of life, they’re cussing and yelling and throwing things, because obviously it’s a lot of stress, you don’t play a soft song to calm them down. You play a loud song to match their mood. Then you slowly, in about 30 minutes, slowly, slow it down, and soon they are sleeping. That taught me a lot about gauging a room. In a theater, people are going to be sitting down, so it’s not like a club atmosphere. So, you come out, you want to hit them, but playing that slow song grabs them in a different way and you could bring them up from there. Or vice a versa, you’re in a club and it’s rocking and rolling and you play that slow song, you’re going to poop the bed. I know. I have done it.”

With a life fully consumed by music, I wondered if there was there a truly defining moment that solidified his commitment or had it always been there, and he just had to enable it? Taking a moment to ponder, “A little column A, a little column B,” Jackson responds. “I went to go see Robert Randolph, mid-high school. I had already been playing, so serious about music. You know, you’re a sophomore in high school, you kind of got things figured out, but also, the world’s your oyster. I went to go see Robert Randolph and he used to bring up people on stage out of the audience. He would suggest, ‘Who plays guitar?’ and someone would come up. If they could really play, great. If they could kind of play, they would make it work. Or jam around it.”

“I was that kid for that night. So, he pulled me up. There was probably about 3,000 people, under the Arch of St. Louis, and I played. They kept me on stage for two long jams, so at least ten to fifteen minutes. He was ‘Wow, he can really play.’ When I got off stage you could feel that energy, and that was the moment. I was just like, that’s what I want to do! “

“If we want to get incredibly full circle, I was at the Beacon (NYC) for the last (Allman Family) Revival show. The last one was where I was doing more of my thing. The first two I kind of helped with. But then the last one at the Beacon, Devon wanted me to play a lot. I ended up doing “The March” with Robert Randolph onstage. We finish and he was so nice, and he said, ‘You sounded great.’ I said you want to hear a funny story? What is even weirder, you know who was on keyboards that night in St. Louis? John Ginty (Allman Betts Band)! So, I played, when I was 15, with John and Robert. We played together again this year and it was great. You can’t make that up.”

Being on the road this year opening for John Ginty and the rest of the Allman Betts Band, Jackson has used the opportunity to present his solo debut to both east and west coasts. Recorded over 3 years in Memphis, St. Louis, & Stewart, FL, Jackson Stokes is a well-crafted recording, that flows gracefully up and down throughout. For the sessions, Jackson called on some of St. Louis’s best along with being graced with special appearances by Johnny Stachela (ABB) on a slide for “Sins are Forgiven” and Shannon McNally lending her vocals to tracks recorded in Memphis.

The songs offer an unfiltered view of life, empathizing with those impacted, and trying to communicate their experiences. Some light and fun, some taking darker paths. The song “You and Your Partner,” is a melancholy number that shares the story of lost love and the pain of seeing their dalliances splashed in front of you on social media. The age-old story of amour gone awry, modernized for the here and now. Not only is this my personal favorite on the album, but before a word is sung, the music paints a somber hue across the horizon setting the stage for what is to come.

Smack dab in the middle of the album is a Talking Heads cover. What? Talking Heads? Mid-west bluesy funk rock sort of guy? Stokes explains it this way, “I believe in a cover. A cover is something that you don’t expect an artist to play, but it makes perfect sense. That’s when a cover is great.” Going into the project with the idea of including a cover, Jackson and crew struggled to find one that fit the bill. Nate Gilbert, sound guy in St. Louis, having listened to the recorded tracks, suggested the Talking Heads. “I’m a high singing white guy. So what is that? That’s the Talking Heads,” he jokes. Surveying the Head’s catalog, they choose “Life After War Time,” using the logic, “You don’t want to do the most famous, but you don’t want to do one no one knows.”

“Take Me Home” sits at the end of the recording. It conjures up a sense of innocence, playing with your dog out back, or your mother giving you a big hug before you head out the door. “I’m big about home, I’m big about roots, and I’m big about where you’re from. An album should take you on a journey, but at the end of it, your right back home,” Jackson asserts. “I have to give credit to Devon for putting that song last. That was his call.”

With touring on hold for now, Jackson is taking to his Facebook page, two to three times a week, performing for all to hear. Just a man and his guitar (and an occasional guest,) going on musical excursions, emanating from his amassed library of influences. Each show taking on its own flavor to keep it fresh. As for living next to Devon Allman, that ended a few years back, but with both still living in St, Louis, when Jackson visits the Allman house, he is not require to sit in the corner anymore.

Comments are closed.