While she was pregnant with me, my mom saw Lou Reed perform his Edgar Allan Poe concept album, The Raven. After the show, she bought a little red baby tee, with an outline of Reed’s face, his name printed below it. She got the smallest one they had — despite the fact that she was the biggest she’d ever been — because she planned to give the shirt to her future daughter, when I was old enough.

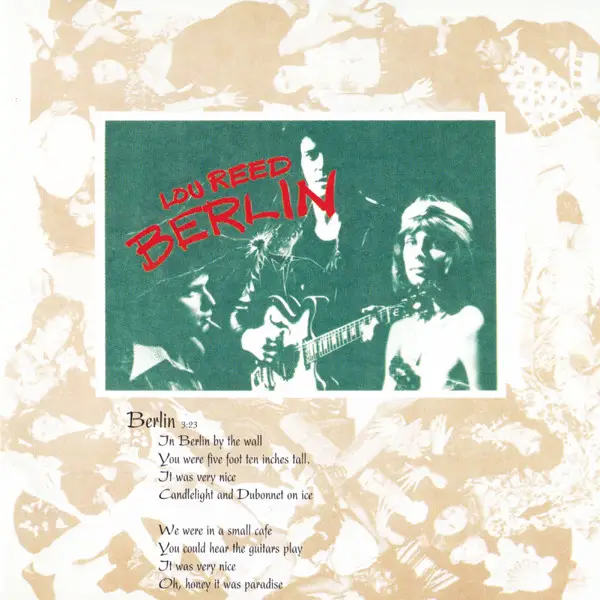

Lou Reed died nearly 10 years ago, in October 2013. I didn’t start listening to him until around two years later. My parents were the kind that didn’t let me watch the movie until I’d read the book, so before I could don my vintage tee I listened to a couple of records. I was instantly in love with the Velvet Underground and veritably obsessed with the casually confident Brooklyn drawl of their lead singer.

That voice was ringing in my head as I browsed Syracuse University’s study abroad program listings last year. I’d been studying French, so that was the obvious choice, but my eyes lingered over Berlin as I hummed Lou Reed’s “Lady Day.”

“I had never been to Berlin when I wrote Berlin. It was an imaginary journey,” said Reed, talking about the song, “The Kids.” “I couldn’t even go coach.”

So I made a decision worth thousands of dollars and five months of my life based on an album Lou Reed recorded without having been to the city for which it’s named. Germany was wunderbar!

Reed said he called the album Berlin because he liked the idea of a “divided city.” He said he could have called the album Brooklyn just as easily. But the music has the perverted cabaret, the purposefully out-of-tune instruments, the choppy underground scene that creeps up like a riptide in a capital city, a seat of government — much like my hometown of Washington, D.C. — after it’s been halved, quartered, chopped, and diced. So much drama and romance exists in that tension, the sneaking and smuggling, the people caught in the space between, the lovers trapped on either side.

Lou Reed lived in that in-between place. Born in Brooklyn, he moved to Long Island when he was nine. Reed was always separate from Manhattan, where the real action was, despite living only a subway ride away. In his numerous songs and albums that chronicle New York City, he sees the city from the inside and outside at once — terrible and glamorous and mysterious, his ultimate femme fatale.

His first shot at the city, in 1958 — a freshman year at New York University — flamed out. A mental breakdown sent him back home before his first year was over. His parents, unsure how to deal with their unresponsive 19 year old, turned to electroconvulsive therapy.

“I watched my brother as my parents assisted him coming back into our home afterwards, unable to walk, stupor-like. It damaged his short-term memory horribly and throughout his life he struggled with memory retention, probably directly as a result of those treatments,” his sister Merrill Reed Weiner wrote on Medium, in a self-published article detailing their childhood.

He recovered — ostensibly — and he dipped, upstate. To Syracuse University.

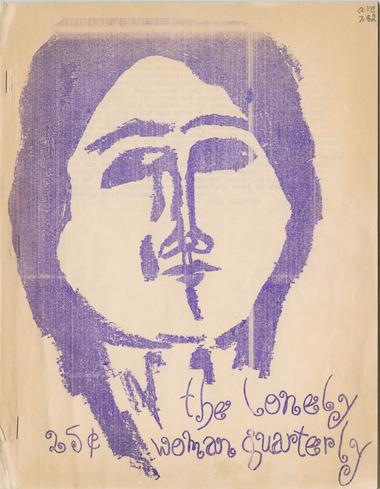

The Lonely Woman

It wasn’t until 2021 that I discovered Lou Reed had also been a student at SU. I was working at The Daily Orange, the student newspaper, scrolling through its archives, when I came across the paper’s Reed obituary. That is when I first heard about The Lonely Woman Quarterly.

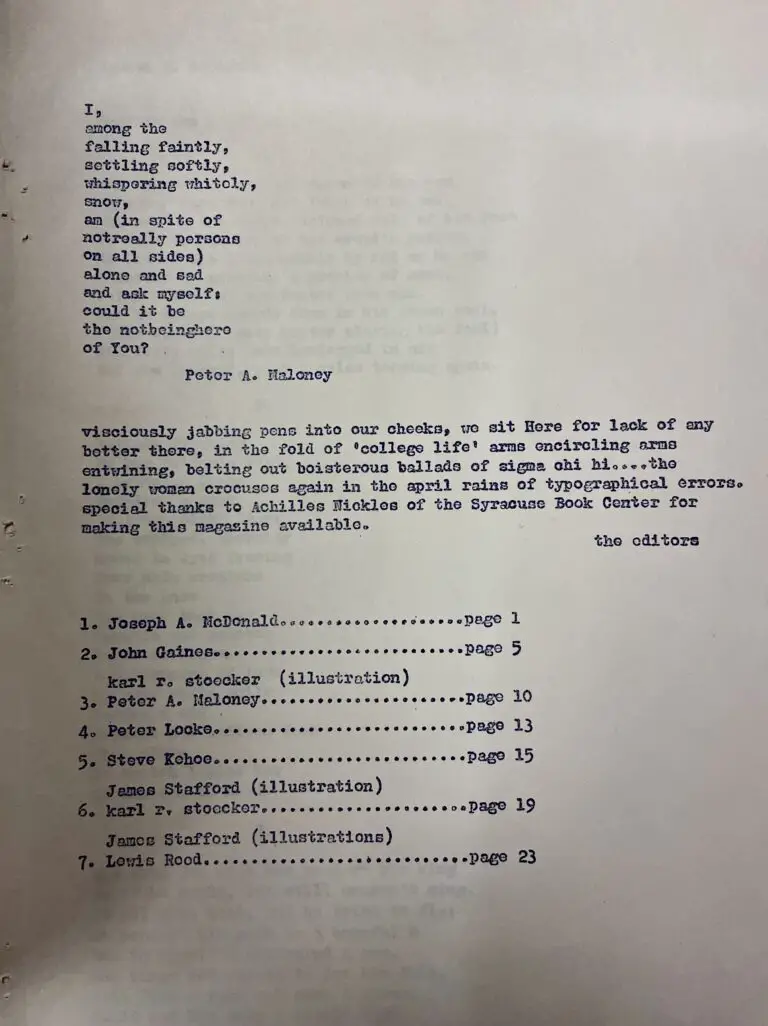

The Special Collections of SU’s Bird Library holds every copy of The Daily Orange, every student zine, thesis and dissertation. In this archive are two original issues of The Lonely Woman Quarterly.

With contributions from “Luis” Reed — as he was then calling himself — “liberal arts student and sometime singer with a campus rock n’ roll band,” Joseph McDonald, James T. Tucker, Karl R. Stoeker and Lincoln Swados, The Lonely Woman Quarterly sold out in one day, according to a May 1962 Daily Orange article documenting the magazine’s premiere.

“The magazine doesn’t contain great literature, but it has material in it that couldn’t be printed elsewhere on campus,” Swados told The D.O.

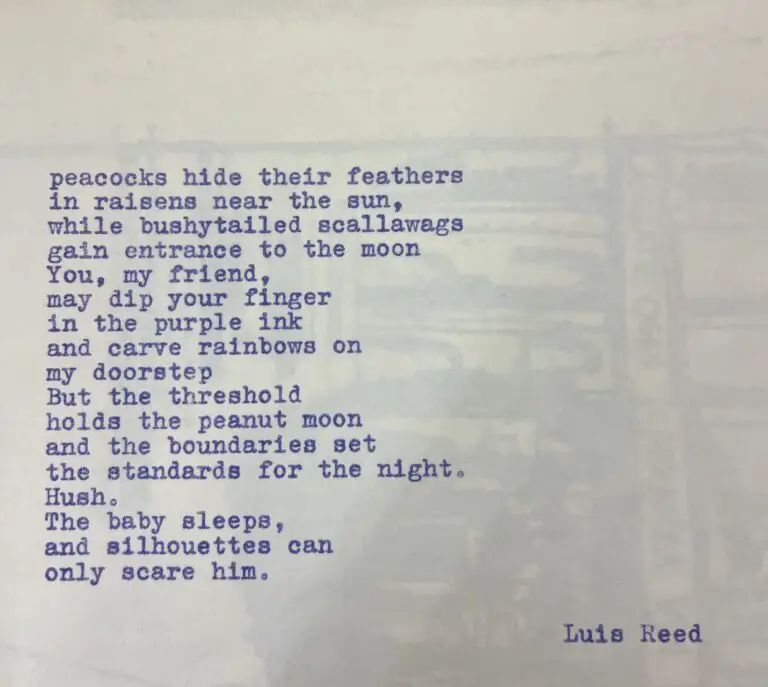

In the 19-page first edition and 23-page second edition, the five sophomores offer poetry and egotism, bleed superiority with a sort of forced nonchalance.. Themes emerged that would later become commonplace in his work: the “Femme Fatale,” “the Beast,” “the Underground.” Paralleling “Luis” Reed’s lyricism in The Lonely Woman, is the music he made during his college years — heard in the resurfaced recordings released last year, Reed’s Gee Whiz, 1958-1964, and Words & Music, May 1965. Looking at The Lonely Woman, it’s easier to understand why this troubled college student, this bridge-and-tunnel-beatnik with a taste for drugs, chose to study “the liberal arts” at a fratty, private university in a small town, an awkward six hours away from home, where he would be reduced to a “sometimes singer” by the campus paper.

Syracuse, the city, has its own draw. It’s here, in the pallid winter and gorgeous summer and frat houses and projects and farmland and undeveloped land. It’s a city built on industry: salt, concrete and ceramics; but the bottom fell out of it all. It’s a city with a highway running right down the middle. A divided city. Something about Syracuse makes you want to prove something to it. Makes you want to provoke. But it’s hard; Syracuse is used to being poked and prodded and it doesn’t scare easy.

The first story in The Lonely Woman Quarterly, written by Reed — of course — is horrifying: it details the abuse of a young boy by his mother. It’s three paragraphs with no title, just “Luis Reed” at the bottom. It starts with the image of a boy looking in the mirror:

“His reflection, ah yes, that was what it was, and he’d remove it to a more shadowy place, where his illumination gained a new fierceness, his countenance new intensity, teeth glistening, hair gleaming. He stared back with love.”

Eventually turning a corner:

“‘Oh no mommy no.’ he found his body undulating, ‘oh no mommy.’ She pulled him closer, her hands pressing him tighter. ‘That’s a good little man, that’s a good little man.’ She was breathing harder now. ‘That’s a good little man,’ she said. ‘That’s a good little man.’”

People still bought the magazine. It was still written about in the highly reputable, independent student paper. This story that shocked in Syracuse might have been overlooked in Manhattan, at NYU. Reed’s calculated tone delivers its sickening punch. Did the waves of electric shock therapy that Lou Reed endured before his arrival in Upstate New York — treatment enabled and encouraged by his mother — feel, to him, like abuse?

900 Ackerman

I live in Syracuse’s Eastside neighborhood. My living room window looks across the driveway into my neighbor’s kitchen, a kitchen that was once Lou Reed’s. He lived at 900 Ackerman, in the attic apartment. On the porch, hanging from the peeling wood, there’s a plaque. It reads “Here lived Legendary Musician, Lou Reed. Take a walk on the Wild Side.”

Now Linus and Thomas, two juniors who could also be referred to as sometime singers in campus bands, live in Reed’s house. I sit in their living room under a poster of Television’s Marquee Moon, with an espresso machine and amp sharing an outlet on the floor beside me. They relay Syracuse’s favorite Lou Reed urban legend; that he was in ROTC but got kicked out for pulling a gun on his commanding officer. Their attic apartment doesn’t look like it’s been updated much since Reed lived here. Thomas said he thought they were hearing Reed’s ghost at one point, but it was just squirrels that had burrowed through the walls.

“I really want us to feel his ghost,” Thomas says. “I feel like I was expecting it during the winter.”

I ask if they hear Syracuse in any Lou Reed songs like I do.

“There’s one song from the banana album,” Linus says, referring to the Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico. “’The Black Angel’s Death Song.’ That’s very much a song about a cold Syracuse day, walking Upstate.”

The song’s psychedelic sound is augmented by John Cale on electric viola. The lyrics: “So you fly / To the cozy brown snow of the East / Gonna choose, choose again.” In the creaking strings of “Black Angel’s Death Song” lies a familiar Syracuse scene: the cold that blows in through the cracks in my apartment windows, the snow pushed up to the side of the street in a gray-brown mass; white snow meeting white sky at the horizon line looks like death, how some nights alone with my meager space heater feels like it.

Slouching Towards Syracuse

David Yaffe, music writer and English professor at SU since 2005, interviewed — or attempted to interview, as Reed had a stockpile of choice words he reserved for journalists — Reed for Rolling Stone in 2007. Yaffe had nominated Reed for an honorary doctorate. Instead, Reed was awarded SU’s most prestigious alumni recognition, the George Arentz Pioneer Medal. Yaffe was set to have a lunch interview with Reed in advance of the reception event in NYC, but the lunch was demoted to a phone call at the last minute.

“We must have talked for half an hour,” Yaffe said. “But it felt like a few months.”

It’s harder to connect in phone interviews; Yaffe said Reed was completely dissociated and closed off for much of the call, until Yaffe mentioned Delmore Schwartz.

In the 1960s, Schwartz was teaching English at SU. The once sharp poetic wit and acclaimed writer was somewhat washed up, paranoid, bipolar. When their paths crossed, Schwartz and Reed formed a deep bond. Schwartz became Reed’s mentor and confidante. In Lou’s words: “Delmore Schwartz is Everything.” Capital E. You can hear it in Lou’s trembling and taxed, yet firm voice when he reads aloud Schwartz’s chef d’œvre, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities.”

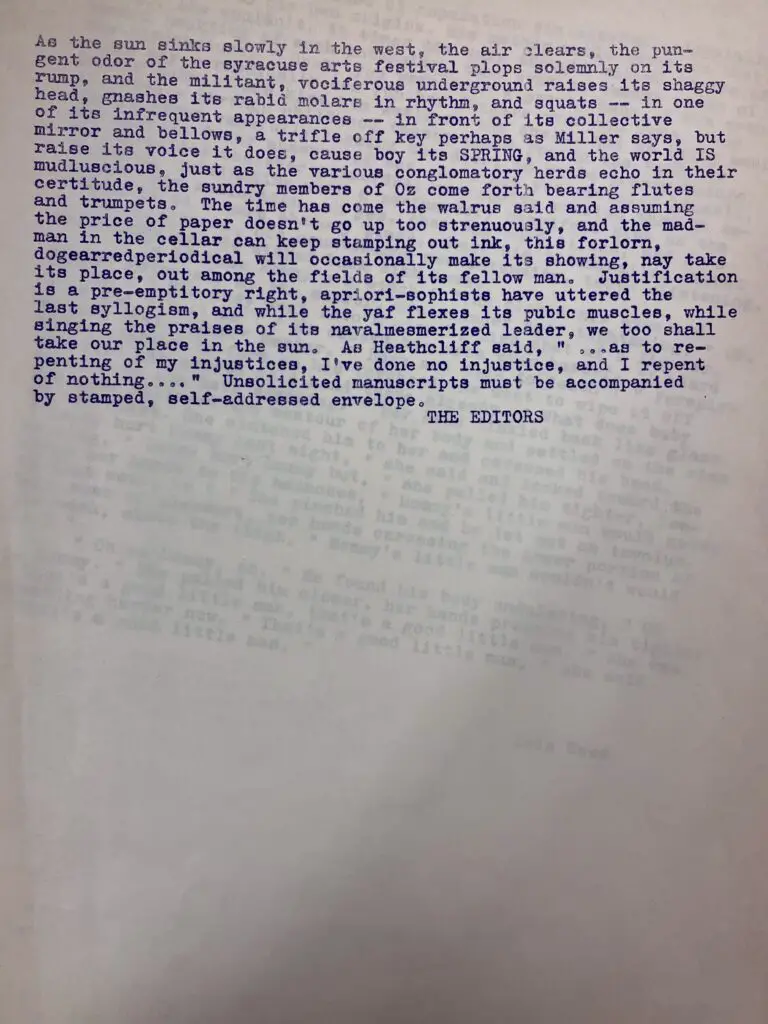

When Yaffe asked about Reed’s Syracuse graduation: “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But when Yaffe asked about Schwartz, Lou opened up, memory jogged, light streaming through, conversations recalled: “We talked about Yeats.” And you can tell, from the first page of The Lonely Woman Quarterly, Issue I. The letter from the editor reads just like the second coming; an Upstate New York version.

“As the sun sinks slowly in the west,” The Quarterly’s editors begin, “The air clears, the pungent odor of the Syracuse Arts Festival plops solemnly on its rump, and the militant, vociferous underground raises its shaggy head, gnashes its rabid molars in rhythm, and squats –– in one of its infrequent appearances –– in front of its collective mirror and bellows, a trifle off key perhaps as miller says, but raise its voice it does, cause boy its SPRING, and the world IS mudluscious, just as the various conglomerate herds echo in their certitude, the sundry members of Oz come forth bearing flutes and trumpets.”

The kids are pulling straight from their lit classes; “blood-dimmed tides,” “slow thighs,” and “rough beast.” Still, something about Syracuse weather provokes Yeats; it’s ominous, “mudlucious.” It’s in the spring that comes on so fast, while there’s still snow on the ground, so everything’s slippery and mud dries on the hems of your jeans. It’s a hesitant spring, the memory of freezing weather so fresh in your mind — a 19-degree day and white-gray sky hovering just over the horizon, threatening to fall over the sunny city at any moment. Spring in Syracuse is miraculous, ephemeral.

The letter continues, “The time has come the walrus said and assuming the price of paper doesn’t go up too strenuously, and the mad-man in the cellar can keep stamping out ink, this forlorn, dogearredperiodical will occasionally make its showing, nay take its place, out among the fields of its fellow man.”

But the mad-man in the cellar, according to The D.O., is really the Savoy Restaurant’s owner Gus Joseph, doing the kids a favor and lending his printer. It’s a familiar sarcastic grandeur, misplaced apostrophes and made-up words, not exactly self-deprecating or self-aggrandizing — it’s just fun, you see them imagining themselves as that looming lion, the Underground, threatening the world as we know it, as the Velvets soon would.

The Lonely Woman’s editors weren’t the only beasts on the horizon. It was the sixties. Joan Didion was reporting the essays that would become “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” The sky was on fire with napalm in Vietnam. In Syracuse, a beast by the name of Urban Renewal was tearing down homes and businesses, to be replaced by a bunch of empty lots and Interstate 81. Reed captures this beast in his stories, in his songs. It’s in the Lonely Woman herself. In the magazine’s credits: “The Lonely Woman has a big nose and satin sheets.” She’s horrible and ugly, yet soft, shiny and disguised. Like a halloween ghost, a mysterious shape floating under the sheet, a vampire’s cape, holes for eyes. Reed’s stories are peppered with these duplicitous monsters. His second story, for example: it has no title, is three pages long, including a prologue and epilogue. It starts:

“Daylight and windy cities and Saturday morning is a beast of legendary tenure.” … “the sun came in through an unobserved crack and shone brightly on my angelic face as I twitched and scratched my early hunger, growling, rumbling down below (although actually not quite awake, just contemplating my inner-most thoughts that buss in a deep fog in waking hours). The beast moved beside me, rolled and signed and hissed through painted lips parted with a now decadent look of sensuousness, lips that had seen things, now parted and twitching, giving forth early morning breath. We had talked of the soul and its death, and my death, the last of my supplanting lives, spent and completely wasted, except for the constant hurt. And she asked me if I had captured my soul and I (having seen nothing but my visions, death I embrace you) had of course replied why no, it has escaped my every turn. “

This is also Yeats, and “Sunday Morning,” and much more. “Sunday morning, brings the dawning / It’s just a restless feeling by my side.” The beast is him, it’s the day, it’s the girl, it’s everywhere. But the beast that moves beside him, that girl he wakes up with, is half beast, half something else. A femme fatale — at once a beast, an angel, your deliverance, your salvation, your dire infatuation.

Femme Fatale

Candy, Lisa, Sally, Jane, Matilda, Caroline, Stephanie, Bonnie Brown, … who’d I miss? Lou Reed’s femme fatale is the beast in disguise, the dark horse, the temptress, the siren, the Lonely Woman.

Syracuse isn’t a natural home to a femme fatale. The town lacks the fantasy and mystery and sense of darkness. Her cave, her cavern, her isolated rock on the shore, her long dark hair she peeks out from under. New York City, though, is brimming with the creatures: the tragic aspiring star, the smoking provocateur in Washington Square Park, the unreachable party girl walking barefoot down the subway steps as the sun rises. In The Lonely Woman Quarterly, the boys are just figuring out how to wrestle these complicated beings onto the page.

A femme fatale finds her power in anonymity, something easier to attain in NYC than in a town like Syracuse, a college campus like SU. The boys of The Lonely Woman find that like a Rumplestiltskin, they can find power in the naming of their girls. Throughout The Lonely Woman are poems by the magazine’s other editors that emulate the “___ Says” styles of later Lou Reed — “Christina’s World,” and “When Karen Walks.” But Reed has a special sense for femme fatale, and he fleshes her out in the second issue of The Lonely Woman, in a story he titled “Mr. Lockwood’s Pool.”

The narrator, walking through a wood — a place that sounds somewhat like Syrcuse’s Thornden Park — happens upon a clearing and finds a gorgeous pool filled with swans and ducks. A woman suddenly appears, like a nymph, and dives into the water.

“I rubbed my eyes with astonishment. It was a girl, thoroughly nude, and in the form of a perfect C, her hands thrust rhythmically in and out of the water, cupped, her face receiving the splash ecstatically and her white teeth glistening… She had long blond hair that now lay in collective sections on her back, the strands coming to spontaneous points”

He becomes infatuated with her, she brings him into the water, she whispers secrets in his ear, says things he’d never heard before. She’s unreal, her beauty celestial, her words magic. Her hair, with its points and sections, alludes to Medusa, suggesting a danger in that beauty, the beast that is just below.

“As I watched it suddenly struck me that she had the long tail of a horse proceeding directly from the tip of her spine, arching and then the fine silky hairs losing themselves in the propitiously slight breeze which presented itself occasionally. She, herself seemed unaware of the appendage, and for all of that was an exquisite creature, with all the attributes that the male species dreamily bestows on members of the feminine gender.”

Now, she walks the line between beauty and beast, joining the leagues of femme fatales Reed created throughout his discography. She’s more than a girl, she’s New York City, she’s an ocean, she’s light, she’s heat, when she talks it sounds like Sister Ray, when she cries it sounds like Venus in Furs. “Strike, dear mistress, and cure his heart.”

At the end of “Mr. Lockwood’s Pool,” the girl with a horse tail tries to lead the narrator through vines and trees, into a clearing with a strange whirlpool black hole, in the sky and in the ground. He’s lost in it, he hears the girl’s voice, sees her face but can’t touch her. The femme fatale isn’t tangible. This girl isn’t within Reed’s reach while he’s in Syracuse, she’s not of this place, she’ll disappear any second, and she does, and the narrator is left alone, missing something he didn’t know he had.

“Yes lochy, that’s it, she yelled, clasped my forehead in her hands, kissed it, and just as quickly she’d appeared, disappeared into the clear, clear water.”

Like only a femme fatale can.

The Underground

SU during the early-60s was a place of conflicting morals and ideals, converse scenes pushing up against each other like tectonic plates. Martin Luther King spoke on campus and Ernie Davis won the Heisman all while Urban Renewal and I-81 destroyed Syracuse’s Black neighborhoods on the Southside. Contradiction was on all sides, but suffocation squeezed out great art.

Contradiction is reflected all over the work Lou Reed recorded while at SU. In 2022, Laurie Anderson released Gee Whiz, an EP containing six songs Lou performed from 1958 to 1964. This small, choice selection, contains “Michael, Row The Boat Ashore,” dated 1963-1964. Originally sung by formerly enslaved African Americans living on South Carolina’s Sea Islands, it was later indoctrinated into American folk tradition, it was re-released in 1961 by The Highwaymen, a band built of white Harvard and Yale business majors, and became a No. 1 hit. At the same time, it was being recited by those protesting in favor of greater civil rights. There’s a contradiction there, of appropriation; of affinity? Lou’s version is quiet, delicate. He was listening to what was popular, then transforming it into the very antithesis of whatever it once was. Know thy enemy. Here emerges the underground.

In Issue One of The Lonely Woman Quarterly, there’s another untitled story by Reed that seems to conflate New York City and Syracuse, like he spent the morning in the city then came home for supper. It opens: “Have you ever sat in the Square trying to look angry?”

The story chronicles a day in the life, like a diary, through Lou’s eyes, as our knowingly pretentious, rambling narrator. Lou ends up with a group of friends at an apartment, where the phone rings, voices half-heartedly debate Dostoevsky, incense burns and his head aches. Then a paragraph breaks free from all of these characters and dialogues and setting. Reed speaks for a second, just long enough to define the Underground of the Velvet Underground like it’s a dissertation:

“Things assumed their normal order, the syntax obscuring the atypical, the falsified dichotomy leaving no room for the incoherent melancholy which is present even in the Hebrais Vision where it was not covered up, parabolic myths in conjecture without relatedness to order. But we had order, and this was purposeful, functional, for what else do we crave if not rules and regulations. How can you deviate if there’s no norm and that’s half the fun so be victorian dear friend and attack the boxlike structure, metamorphisize in extenuating circumstances and feel the joy of guilt, which you actually feel anyway but not correctly, break with the tintinnabulary logic of your mind and enter the chaos, but be strong and truthful without pretensions, and THEN disbelieve, but not before, or alas, alack you are but one of us and worse yet, me, for I’m the worst of the worst, the phoniest of the phony, the weakest of the weak, the strongest of the strong, setting up new settings for the old, new mores for the sacrosanct, typification of any for non-existent disillusionment in endless streams of group discussion, exchangement of neurosis, boastful, dearheart, and a more stringent benefactor you’ve never seen.”

With the Velvet Underground, Lou Reed social climbs from behind the ladder, he’s real and fake, he’s playing truth and he’s a terrible liar. The game’s not to make sense, it’s to keep up. Manifesto-like, Reed defends his four-year sentence in Upstate New York: “to be strong and truthful without pretensions, and THEN disbelieve.” Underground, inside of contradiction, is where Lou felt most at home — a beatnik that joined ROTC, a rock star playing for the fraternities, a gay city kid at a preppy, private university. He wants to play football for the coach.

Comments are closed.