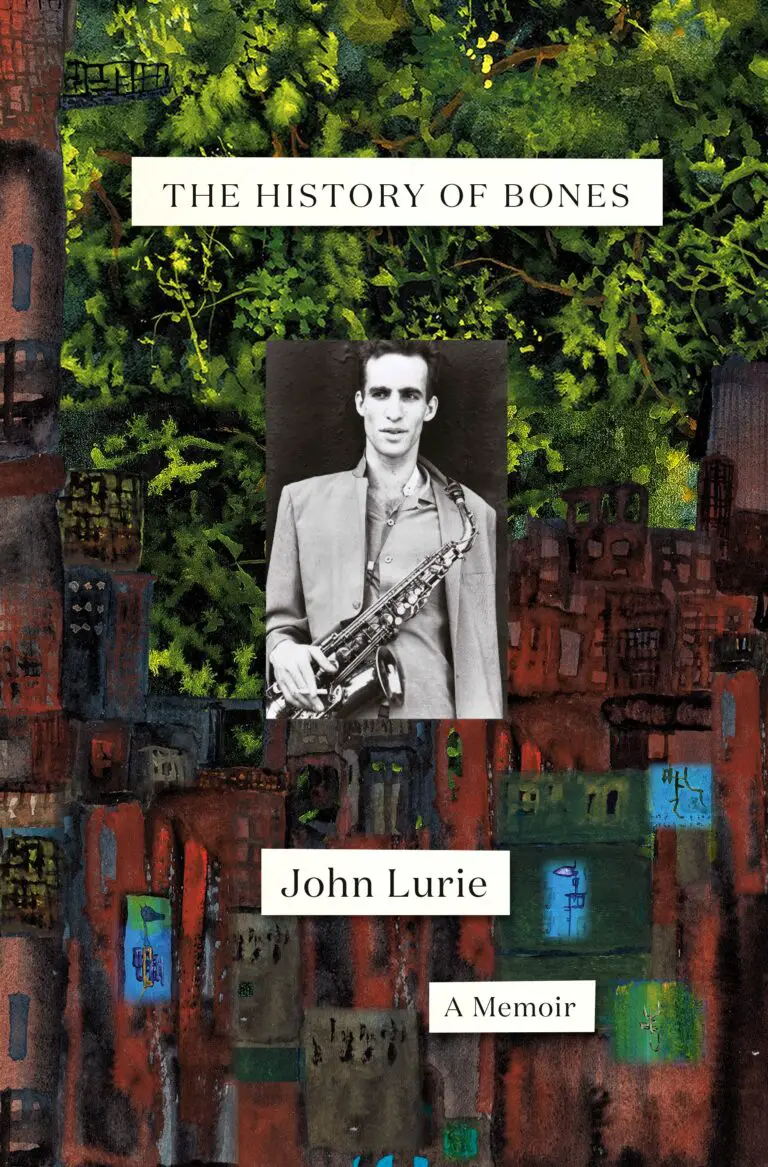

As anyone who has seen the TV series Painting with John can attest, John Lurie is a storyteller of the highest order. In his new memoir, The History of Bones (Penguin Random House), Lurie weaves a gloriously gritty, informative and entertaining portrait of Downtown NYC in the 1980s. The universe below 14th Street was a creative cauldron where edgy musicians, filmmakers and fine artists – giants like Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Debbie Harry, Madonna, Bowie, Eno and Jim Jarmusch to name a few – co-existed and often collaborated to create art that still casts a profound influence on today’s culture. As for Lurie, he ultimately emerged as a player in all these spheres. He was a uniquely stylish lout with the driest of wit, someone dubbed “The Coolest Man of Earth” by a host of style arbiters for a multitude of very good reasons.

John Lurie was a true “It Boy” of this mythic era when Downtown NYC was cheap, dangerous and full of creative action. He was co-founder, chief composer and the angular “face” of The Lounge Lizards – the sharp-suited, globe-trotting punk jazzbos who helped define the “No Wave” genre. As his musical light started to shine, Lurie added a high-profile acting career to his creative portfolio. This came via scene-stealing roles in Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise and Down by Law, Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ and others. The relentlessly touring musician also somehow found time to score 20 films including 1995’s Get Shorty, which earned him an Oscar nomination. And before he devoted his creative energies almost entirely to visual art in the early 2000s, Lurie garnered more limelight via romances with boldfaced names like model Veronica Webb and Uma Thurman, by cat walking for European fashion designers and in a vast number of interviews – ones where he pulled no punches in his controversial assessments of his contemporaries and the entertainment business writ large.

Like Bob Dylan’s Chronicles Volume One, The History of Bones only tells part of this artist’s sprawling story. It concludes with a performance in Stuttgart on the New Year’s Eve 1989, as a new decade and artistic sensibility dawns in Downtown NYC. His subsequent years out of the spotlight due to chronic Lyme’s Disease, along with his development as a painter, his first TV series Fishing with John and musical ventures like his bluesman alter-ego, Marvin Pontiac, and his John Lurie National Orchestra, are only referenced in passing. But, oh what a story it is, even in part! And unlike the mumble-prone Dylan, I cannot wait to get my hands, err ears, on the audiobook version of Lurie’s memoir. It is sure to be told in a comic deadpan that brings to mind the Godfather of Alt.Comedy, Steven Wright.

Lurie’s book begins with his childhood, one spent mainly in Massachusetts. By 16, he had discovered the harmonica and jammed on stage with the likes of Canned Heat and Mississippi Fred McDowell. Lurie also graces readers with the oddball story of how he got his first sax. It came as a gift from a quasi-homeless man on a dark, empty street at 4 a.m., a man who claimed he was seeing statues turning into angels at the time. After his father’s death, teenage Lurie went a little off the rails. He became involved in petty theft and travelers’ check schemes before turning into a hardcore kundalini yogi and vegan. At this juncture, he would fast and practice sax for days on end, remain celibate (something that would quickly pass) and also ride his bike naked in the streets in the early morning. Lurie’s journey of lurid begins when he loses his virginity and gains a bout of gonorrhea from Crystal, a groupie who had reputedly slept with Jimi Hendrix the week before.

Much of Lurie’s story involves his long affair with and dozens of attempts to kick heroin. His first taste comes courtesy of another famous 1980s icon, Debbie Harry. It’s one that will lead to a seven-year long habit that puts him in the company of junky jazz greats like bassist Sirone and drummer Bobo Shaw. It also leads him to the doorstep of the legendary Dr. Gong, the Chinatown acupuncturist who reportedly helped Keith Richards kick his habit.

Even as his career as a critically-acclaimed musician takes flight, Lurie lives hand-to-mouth, due to the hunger of his habit and the petty wages paid to touring jazz musicians. His fortunes are buoyed by landing government support in the way of a monthly disability stipend and a $55 apartment on the Lower East Side, two things he wisely holds onto for years. Unfortunately, his nicely priced abode is on a block he calls “Third Street Hell.” It was right across from a notorious men’s shelter. This leads to a few robberies, muggings and many a night spent sleepless due to the screams and fights unfolding on the street below.

Lurie pulls no punches in his attempts to set a few records straight. Most notable is his beef with director Jim Jarmusch in whose debut film, Stranger Than Paradise, Lurie first gained acclaim for his acting.

According to Lurie, the original story idea for the film was his – that of a low-level gambler who has to take care of his visiting Hungarian cousin. When the movie comes out, Lurie’s expected story credit is nowhere to be seen, but he continues to work with the director anyway. After working with Italian actor Roberto Benigni in Jarmusch’s Down by Law, Lurie writes a script for the Italian to star in. It’s inspired by a true-life story Lurie is told about an Italian cowboy who challenges and beats the legendary Buffalo Bill Cody in a cowboy contest. Lurie’s script has Benigni traveling across a surreal Western landscape with a Native American. When he finishes the script, he sends it to Jarmusch for his input … and hears nothing. Later, when he is just starting to raise funds for his film, Lurie hears that Jarmusch is making a surreal Western with Johnny Depp and a Native American sidekick called Dead Man, a virtual copy of his premise. Jarmusch’s film goes ahead; Lurie’s never happens.

Lurie’s long and competitive relationship with his “best friend,” the late painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, weaves throughout the memoir. In its early days, Basquiat is homeless and crashing at Lurie’s pad for almost two years. They spend much of their time painting together, and the then-unknown Basquiat looks up to Lurie as his Lounge Lizards begin to take off. Even with notoriety, the musician Lurie is still living hand-to-mouth. Shortly thereafter, Basquiat’s career takes off like a rocket ship. With it, Basquiat flaunts his money, fame, belongings and even competes for women with Lurie. Lurie also expresses the deep hurt over Basquiat using his idea for a poster for group show of their own – of him and Basquiat facing off in boxing trunks – as the image Jean-Michel uses for his famous collaboration with Andy Warhol. In the end, he laments the loss of this close, competitive friendship that helped both excel.

Lurie has both praise and criticism for some of his musical collaborators, as well as many funny meetings with other Downtown NYC boldfaced names.

He calls quixotic guitarist Marc Ribot a genius for finding a place in his and many of the other obtuse musics he has collaborated on. His comments on later-day Lizards’ six-stringer Brandon Ross are less in-depth and kind, basically only saying that his dreadlocks smelled funny! He tells a funny story about twisting the arm of a man trying to intercept a joint being passed to him at a party by actor Willem Dafoe… only to discover it is that of David Bowie! He passes judgement on Knitting Factory impresario Michael Dorf by claiming that “dorfed” became a popular verb used by musicians of the era to express when they had felt ripped off. A truly funny story involves him going to Chinatown to buy a dead eel to photograph for the cover of the album Voice of Chunk. Strangled, bashed about, it’s an eel that refuses to die…until taking a four-floor drop off his windowsill and crawling a half-block in the gutter.

An overriding sentiment of Lurie’s is that the acting overshadowed, or at least got in the way of people fully appreciating, his music. Thought they toured extensively and most successfully in Europe and Asia, Lurie feels The Lounge Lizards never fully broke through or rose above the “fake jazz” label put on them in the early 1980s. Lurie took work scoring and acting in films to support his band and their original music. And at the end of his memoir, Lurie is using in excess of $100k of his own money to record the Lizards’ 1989 masterwork, Voice of Chunk, because no U.S. record company would sign them. In the end, it resulted in Lurie producing another memorable piece of art, a hilarious, 30-second, late-night TV spot to market the disc directly to consumers just like OxyClean, one that included four of his ex-girlfriends as models.

The above just scratches the surface on the many colorful anecdotes and salient observations in Lurie’s book. You can almost picture him spinning these yarns around a cracker barrel fire in a metal trash can or dumpster on Avenue C.

This is certainly one of the best and least scrubbed clean memoirs coming from a Downtown hipster of the era, a place-in-time that is now birthing a motherlode of such books. I, for one, can’t wait for him to get us another installment, one charting his less profiled journey from edge-cutting musician through illness and solitude to the painter-raconteur-philosopher that he is today.

Comments are closed.