Note: the events in this article represent certain activities that might have been entertained by a young girl in New York, i.e. of the author’s general height, weight and build. She is aware that her Steely Dan obsession isn’t punk rock at all.

It’s almost seven in the evening when I leave work, and realize that the temperature has dropped about twenty degrees since I stepped out for lunch in the afternoon. The sheer polka-dotted black shirt that I wear in lieu of a blazer is only just keeping me from shivering. Pushed, I shove through the multitudes of crowds on Madison Ave, scraping through the suited M&A types that storm out of the Black Rock buildings on both sides of the road. After having been paid—for the first time in the past couple of months—I plug in my headphones and hit ‘play’ on my ‘Reigning Gauraa’ playlist that I save for my few and far between empowered, optimistic moments. I mouth the lyrics to one of my favorite Steely Dan songs, “Glamor Profession” as I reach the 51st St station and somehow manage to board the 6; my shoulders droop, my eyes begin to close, and the track’s smug idiom-y delivery takes on a narrative arc of its own. I begin to think about my own glamor profession in the music industry—not the glorified, romanticized version involving creative freedom and backstage passes that I save for my relatives and ex-boyfriends—but the actual dreary, underpaid selection of gigs that I tie together and loosely categorize as a ‘job.’ At the Union Station stop, the crowd spits me out of the train. I decide to take a few minutes to myself before I transfer to the L, where I routinely endure the hand-quilting, alt-lit-reading crowds on my way home. I flee onto 14th street with what feels like a self-aware, if slightly jaded, grin. I’m nineteen-going on-Donald-Fagen-level-cynicism, thinking about how the music industry is a concession, but this time from the perspective of a fictional albeit big time coke dealer.

I was dragged into the world of Steely Dan as a reluctant seventeen year old, when a boy I was seeing professed his love for the band over dinner. Unlike the rest of my friends, who had previously shared with me scarring accounts of their mothers dancing in the kitchen to “Peg,” my parents didn’t introduce me to the jazz fusion duo. (In fact, they were under the impression that Steely Dan was the name of Broadway production, until I clarified later in 2013.) Knowing little about them at the time, I met his confession with scornful second-hand opinions that expressed disdain for the band’s self righteous studio attitude. Though I had my doubts about a band named after a dildo in a William S. Burroughs novel, I was taken in by how every conversation with him was riddled with footnotes that cited a Steely Dan song. When he moved to another city, I sought solace in the Dan discography, attempting to match their apathy for sport. The more I listened to them, the more I realized that they weren’t writing “cocktail jazz” as much as they were playing the armchair detective. Under the silk harmonies and solo horn sections, lay snarky lyrics and double entendres, that you had to be clever enough to unveil. Walter Becker and Donald Fagen were the two people you befriend at a show over cigarettes and a mutual dislike for The Hold Steady.

When I walk around Lower Manhattan, Two Against Nature guides me like color-changing lyrics on a karaoke video screen. I hear “What A Shame About Me” when I walk down Broadway and see Donald Fagen stacking cutouts at the Strand with rigid self-pity. A few blocks later, when I pass by a Dean and DeLuca, Becker’s bubbling bass on “Janie Runaway” comes to mind. I ricochet into the fall of my sophomore year in college when the boy I was seeing would visit. On Thursdays, he would fly out to New York and I’d get takeout from Dean and DeLuca’s, and we’d reenact the song. It was a theme park equivalent of a relationship. Most of our texts were laden with Steely Dan references—when I’d get mad I’d refer to him as Randall, Pixeleen’s “as-if boyfriend” from Everything Must Go, and he’d tell me how “the connection seemed to go dead” whenever I had droned on for too long about a new band I interviewed. We’d argue a lot about “Green Book,” a song that I was positive was drawn from J.D. Salinger’s eponymous character in the short story “Franny,” who also carried around a green book. One October night when he was visiting, he insisted on taking me to Rudy’s in Hell’s Kitchen to pacify me after we had gotten in a fight. Rudy’s was the bar in which the protagonist of “Black Cow” worked and advised an outrageous, high, mess of a woman in Aja. (We had gotten into an even bigger fight when we found out that the place wasn’t nearly as seedy as described in the 1977 song, and my fake ID landed a spot on their ‘Wall of Shame’.)

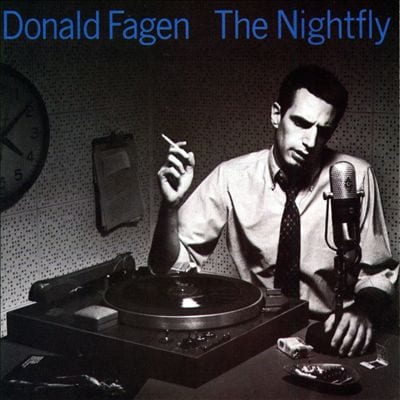

My train of thought is rudely interrupted when a breeze wafts through my hair. Shivering, I decide to stop by my favorite ale house on Bleecker street to warm up with a quick drink. As I place my order, I catch a glimpse of Bleecker Street Records. There, I had picked up a copy of The Nightfly a summer ago. I think about the album cover and wonder what Donald Fagen was trying to imply by sitting in front of a record player, with an ashtray and a pack of Chesterfield King cigarettes. I can’t quite place my finger on what it is, but I know that it makes me want to drink in inspiration. I take a swig from my mug and dial my friend. ‘Meet me at midnight’ I say in a rather coy manner, ‘at Mr. Chow’s,’ which more likely than not, gives away that I have been drinking. Meet me at midnight at Mr. Chow’s? I’m not a character from a ’74 neo-noir mystery film. I send her a text with a link to the lyrics of “Glamor Profession” in order to clarify. Knowing that going on impromptu Steely Dan inspired field trips is my version of getting a radical, post-breakup haircut, she agrees.

I had looked up Mr. Chow’s before, and was well aware that it was a high-end Chinese restaurant. To someone who survives almost exclusively on takeout, upscale Chinese sounds like a fifteen percent increase on the prices of the Szechuan Dragon noodle house. When we get there, both dressed in some kind of casual denim variation, we are reminded to never buy anything from a retail company that identifies itself as “the fast option for fashion” again. As we wait to be seated, I see a woman in a silk gown swirling vintage port wine at her table. She looks like a wizened vestige of the woman on this month’s Vogue cover. The host walks up to us to inform that the kitchen is about to close in five minutes. ‘You can stay if you place your order right away’. I make a mental note to check details in the future, just in case timings from a thirty-three year old song change. ‘Sure, that won’t be a problem’, I assure him. I already know we’re going to order Szechuan dumplings, like in “Glamor Profession.”

The waiter comes to take our order, glancing at our denim apparel in the condescending manner high-end boutique sales assistants look at you when you try on something they know you can’t afford. ‘We’ll have the Szechuan dumplings, please.’ ‘And for your entrees?’ I glance down at the menu, trying hard to keep my jaw from falling down. There are few selections priced in double-digit numbers. “That will be all, thank you!,” I say, hoping he will disappear into the kitchen with our order. With a sharp grin, he tells us there is a strict $40 per person minimum charge. I entertain the thought of dining and dashing for a brief second, but then decide the odds of outrunning the security are probably slim. We order just enough appetizers to reach the minimum. ‘Do you think they have a pool going on to see how long it takes for us to give up and leave?,’ I ask, trying to make light of the situation. We eat, what could easily be most mediocre set of dumplings ever, in silence. How the mighty have fallen.

The evening suddenly becomes more embarrassing than the culmination of the wall of shame incident at Rudy’s, and the time my mother commented on my “Any Major Dude”- inspired squonk cover photo on Facebook, asking me to take down the “ugly, crying mythical creature” from my profile. This is not as bad as the time I danced a little too long with Cuervo, the fine Colombian, and sang “Hey Nineteen” to an empty karaoke room on my own nineteenth birthday, I remind myself in consolation.

Maybe next time I’ll try reenacting an easier reference. Like, I don’t know, taking “off to Barbados, just for the ride?”

Comments are closed.