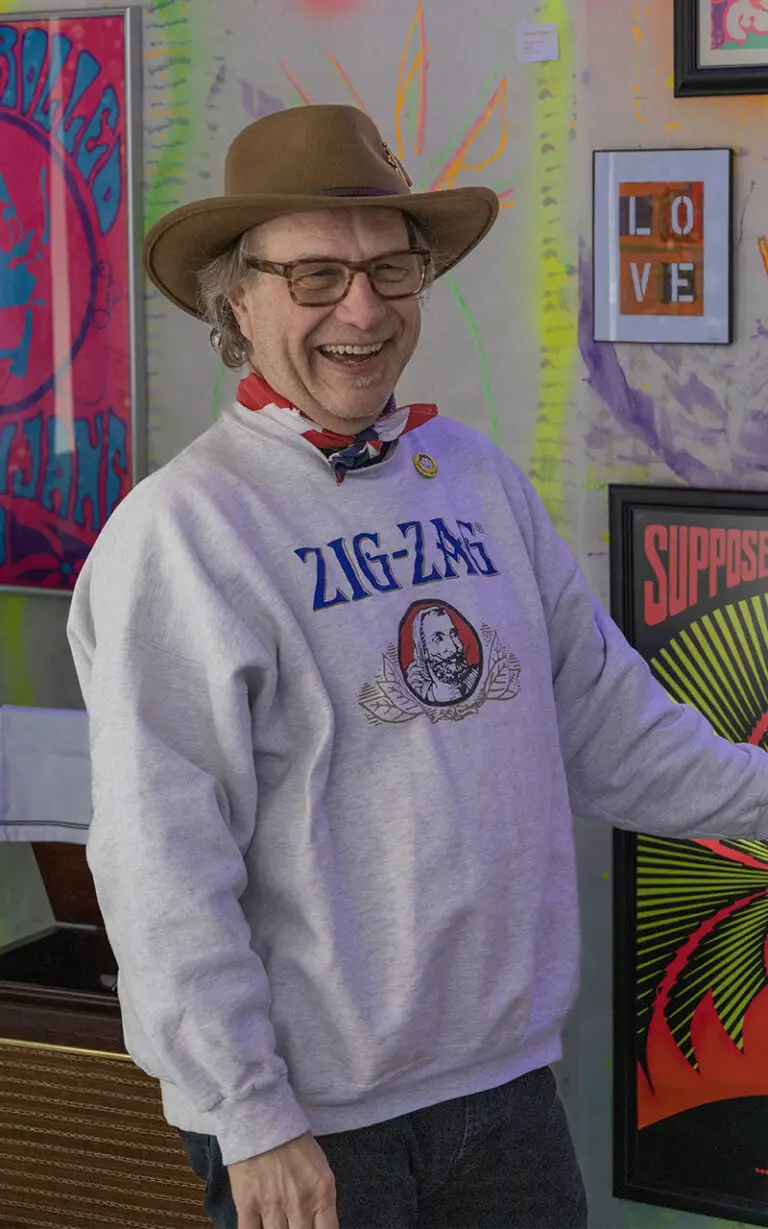

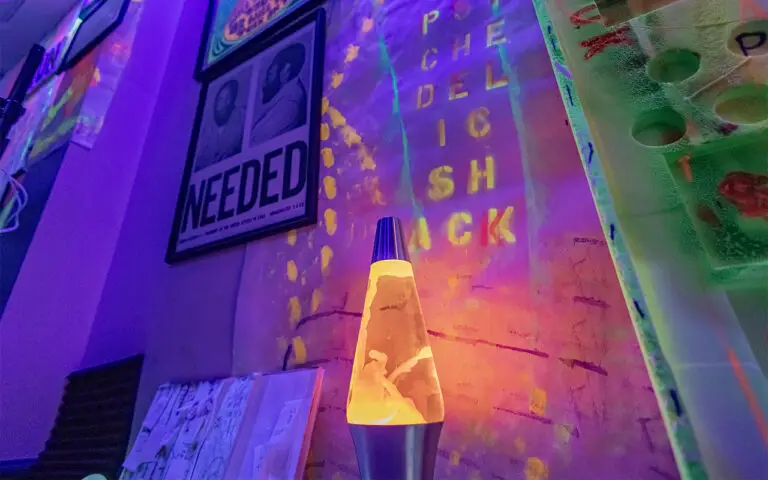

Visiting Alex Miller’s “Psychedelic Shack” vintage-memorabilia installation at the new Glove Cities Art Gallery in Gloversville, NY is like walking into a time warp that is part museum and part kid’s bedroom circa the early 1970s or late 1960s.

Miller, a former music industry executive, promoter, disc jockey and stand-up comedian, would agree.

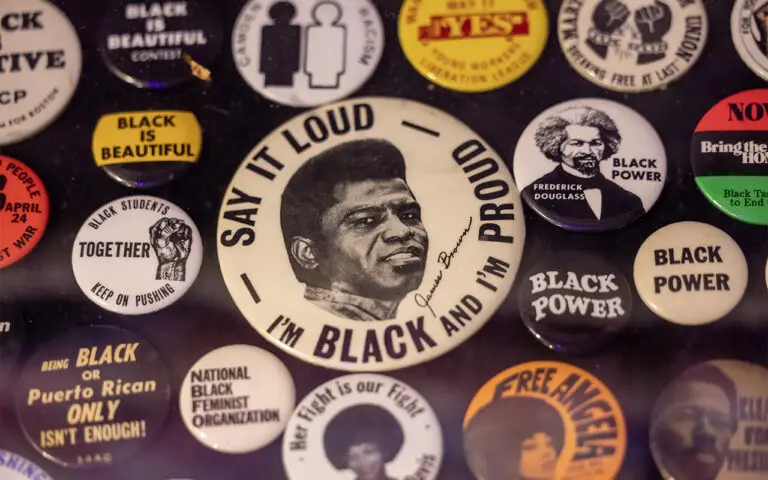

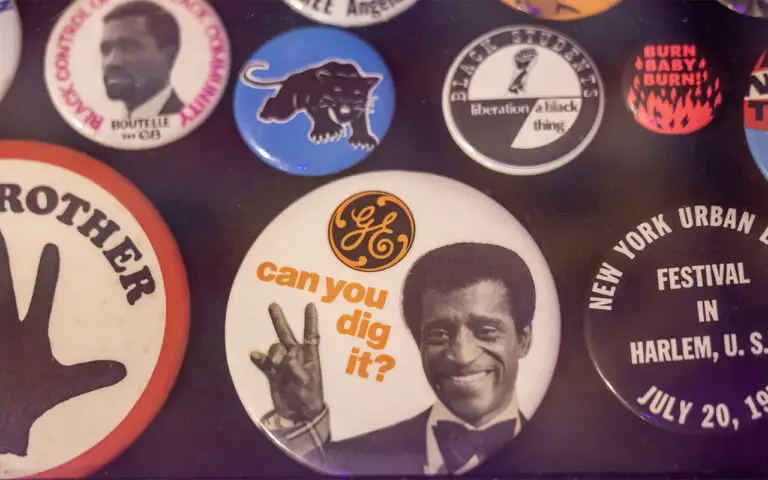

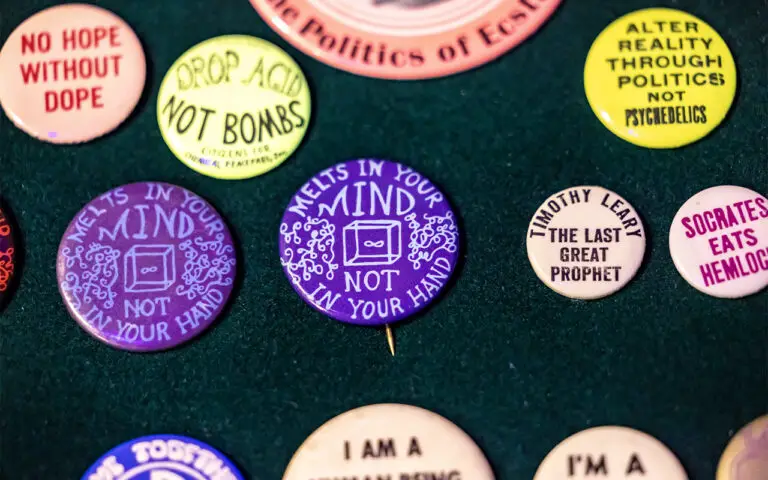

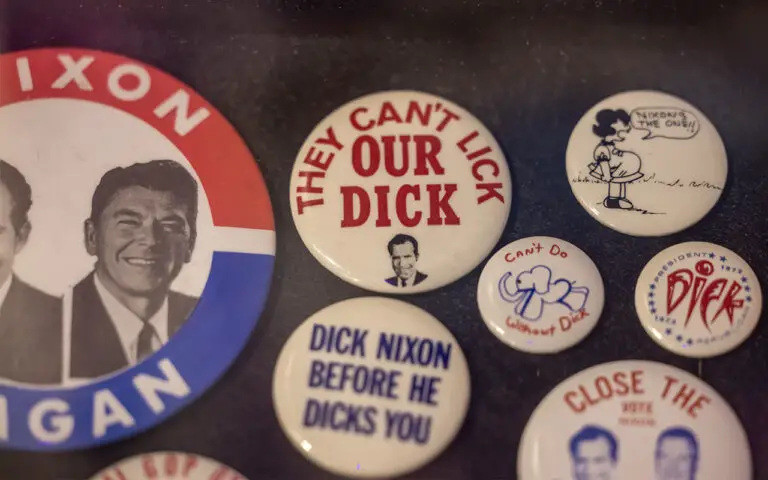

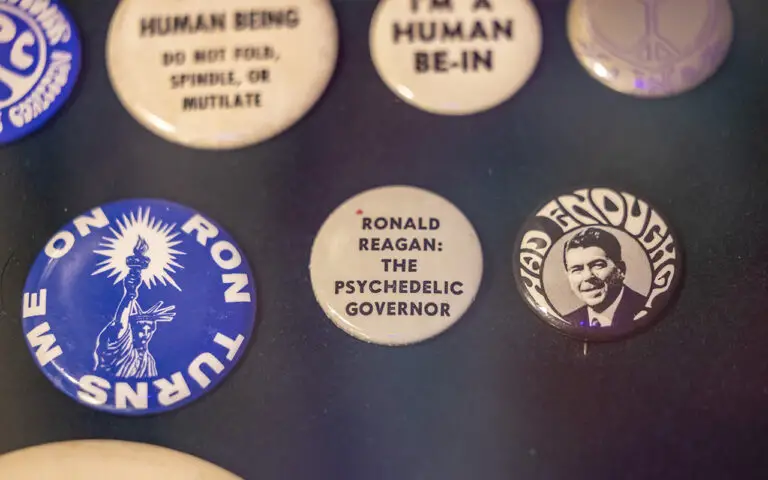

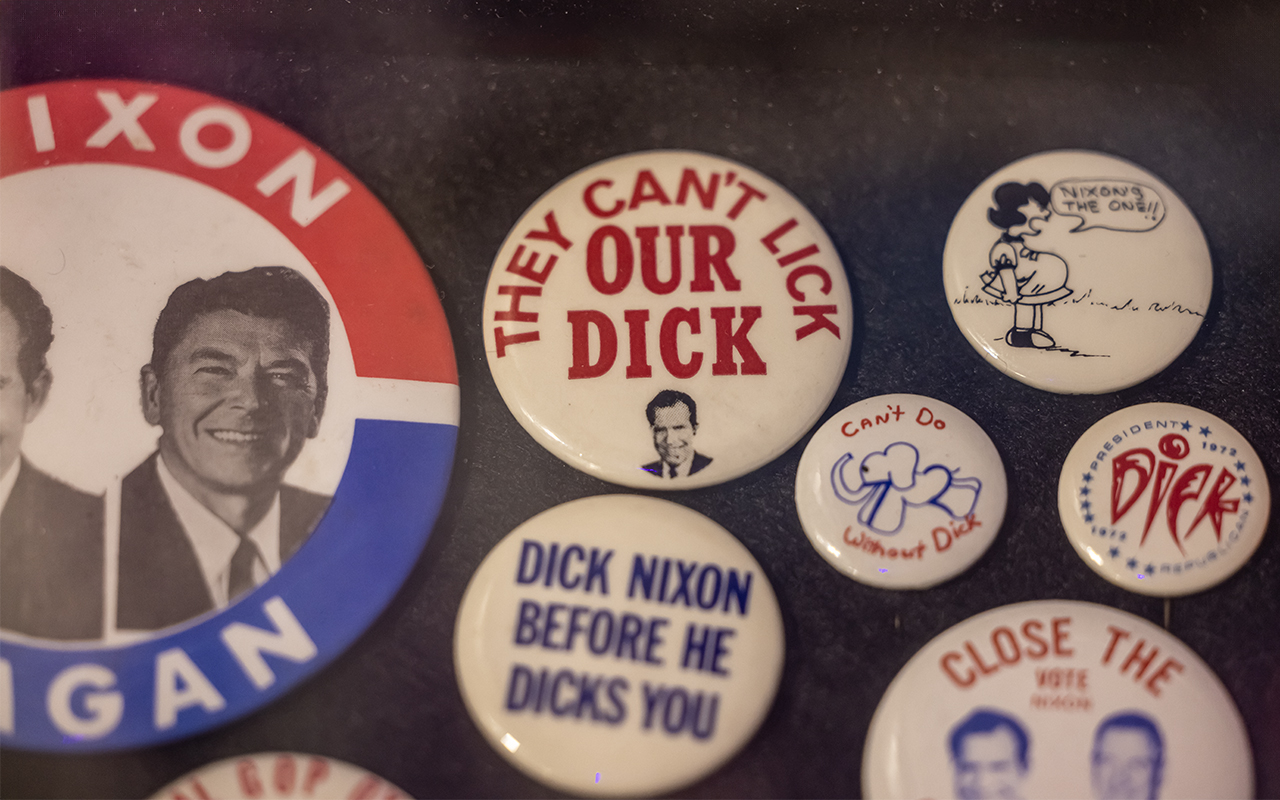

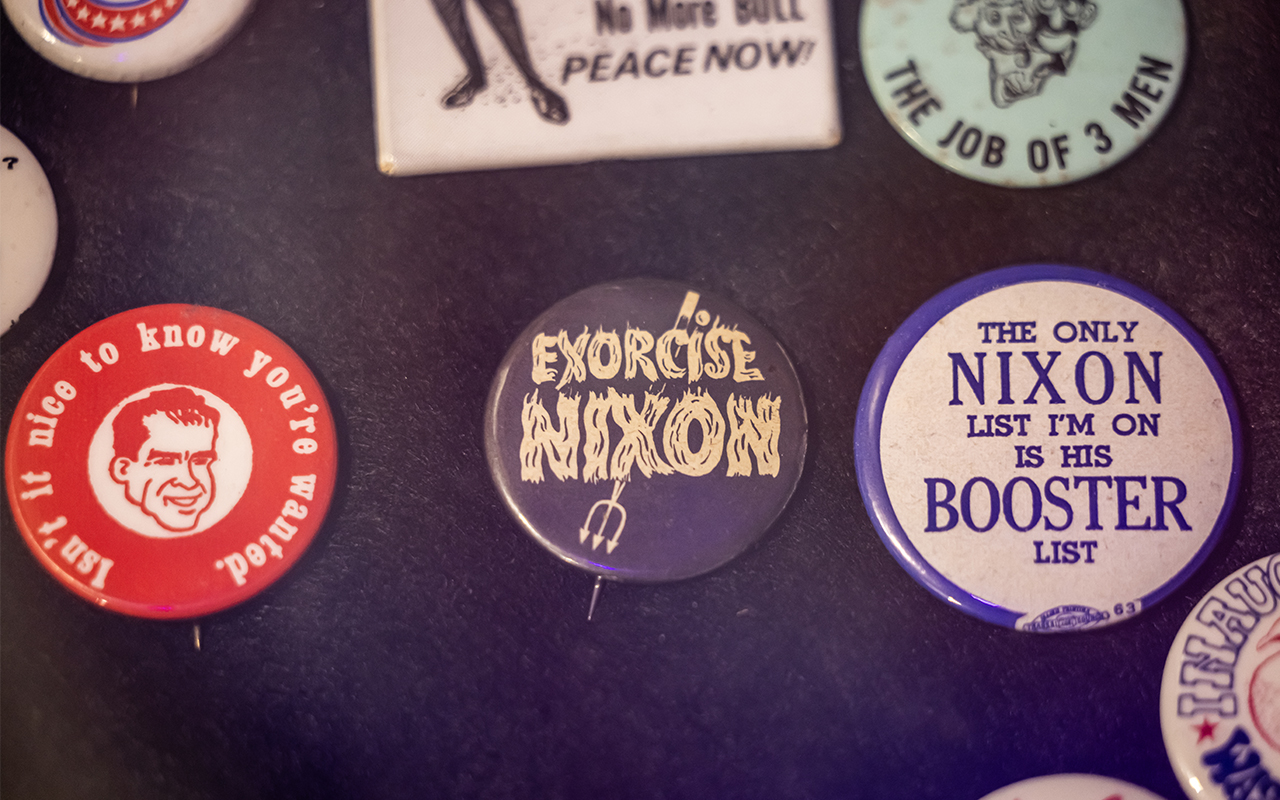

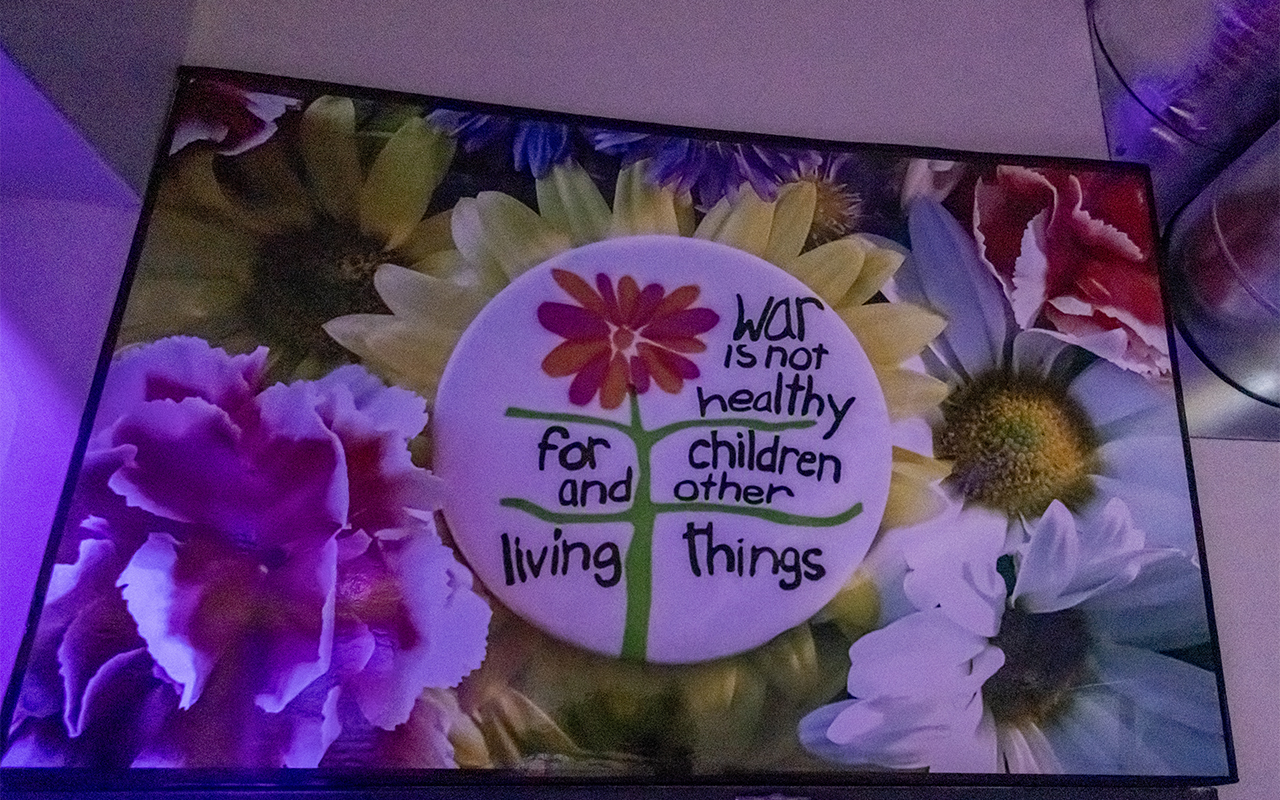

At the tender age of 11 in 1968, Miller began collecting everything from political campaign buttons to social consciousness posters, band memorabilia, vinyl albums and, most recently, hi-fidelity sound equipment, which he has taught himself to repair and preserve.

Now 68, Miller has amassed a diverse collection of vintage stuff which he bills as “The Psychedelic Shack: Tune In/Turn On – Politics, Pop Culture and the Rise of Hi-Fidelity” for the installation. He is sharing it with the public now through the end of February at 52 Church Street, Gloversville. Hours are Thursdays and Fridays from 4:30 – 7 PM and Saturdays from 11am – 3PM.

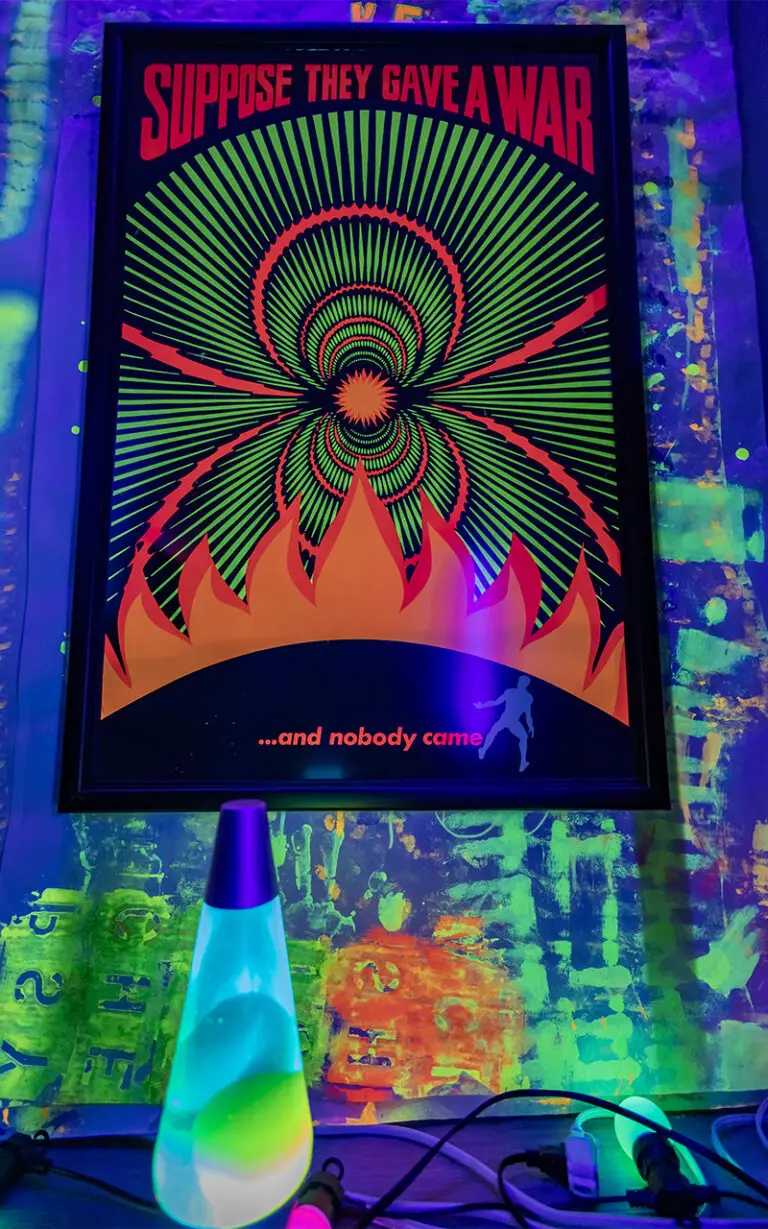

The collection includes tapestries, posters, several vintage issues of Life Magazine, lava and other period lamps, speakers, a turn table and 8-track player, a combination reel-to-reel and 8-track machine and such quirky relics as a cone-shaped fireplace, a purse with peace-sign zipper pulls, a 67-67 wall-mounted phone, and a “Columbia stereo console reimagined as a Mid-Century Modern cocktail bar.” All of it is for sale to benefit the local arts alliance.

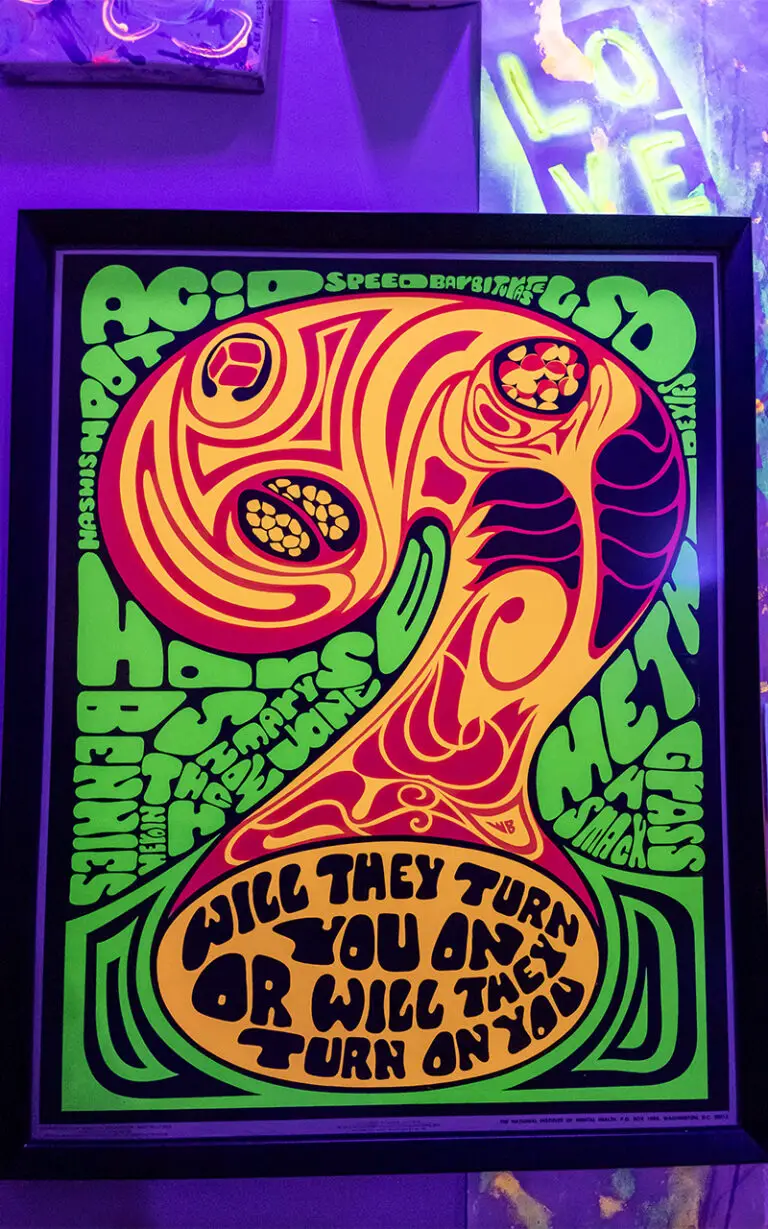

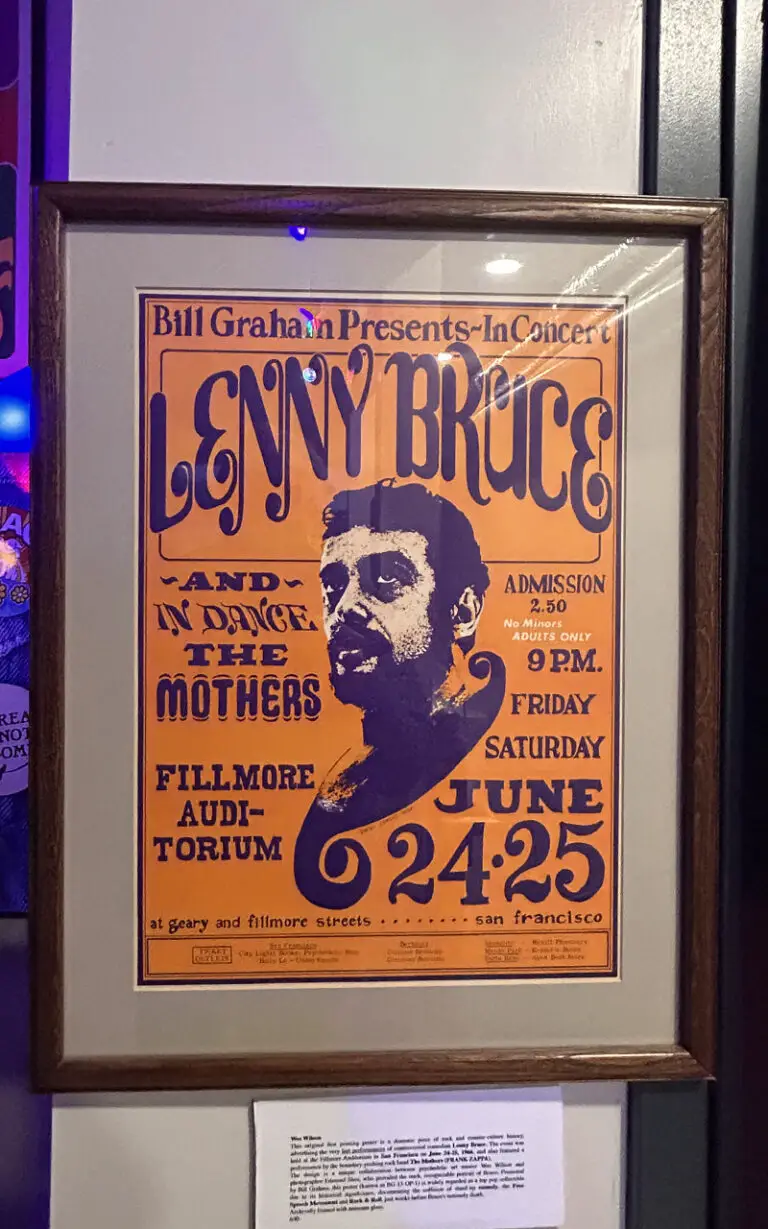

From a visual-arts standpoint, the installation features a dizzying “Vari-Vue Lenticular” op-art piece from MOMA and a series of counter-culture, sometimes psychedelic-art posters, including an “anti-drug, psychedelic, blacklight American political poster made by the U.S. government” with the headline, “Will They Turn You On or Will They Turn on You?”

A placard describes the piece as “trippy …in the style of pro-drug head shop posters” but it is “actually anti-drug propaganda” produced by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1970.

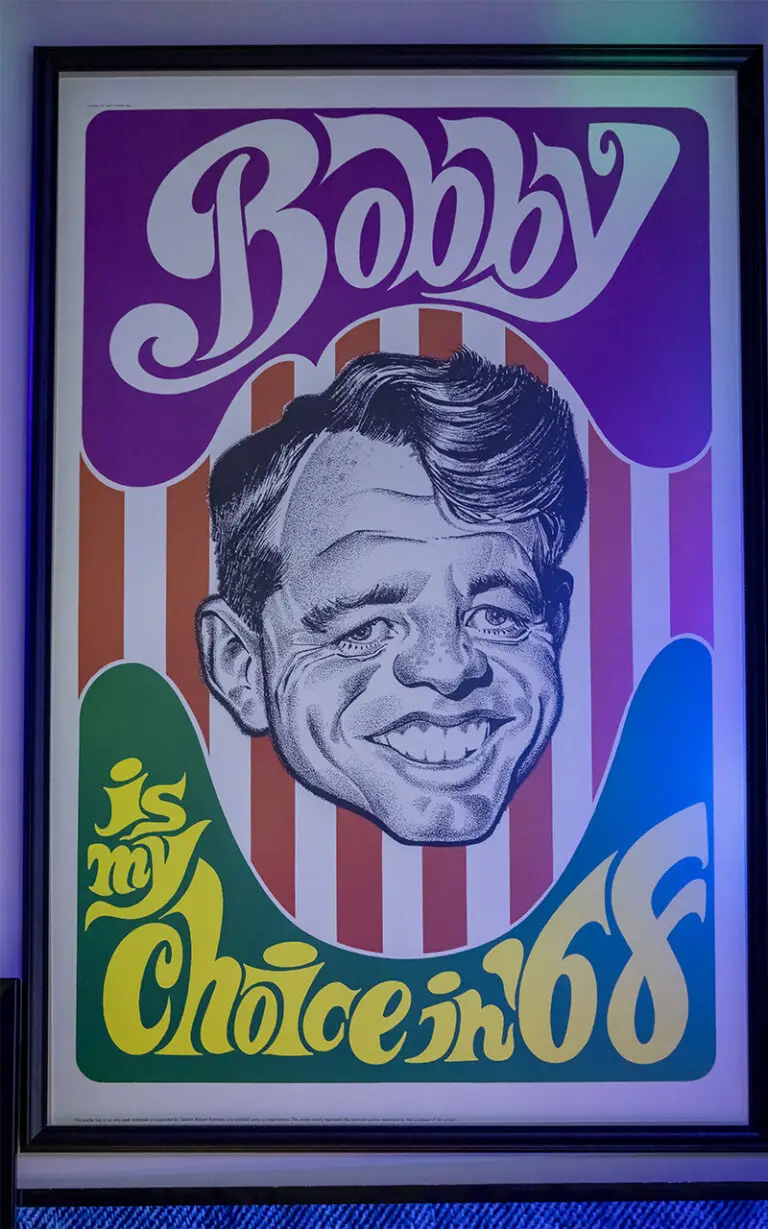

Another poster depicts a caricature of Robert F. Kennedy a la Mad Magazine styling and framed by a psychedelic border. Still another showcases a picture of Frank Zappa on a toilet and is titled “Phi Zappa Krappa.”

Describing his repertoire in an interview Jan. 31 at the gallery, Miller said he was “fascinated by [counter-culture] graphics” while coming of age in heavily Republican Pine Bush in Ulster County, NY in the late 60s and 70s at “the intersection of the advocacy of LSD and the free speech movement.”

Political violence left its mark, too.

“There was something about waking up, turning on the TV and seeing that Robert F Kennedy had been assassinated that really tears at life; it made an impact,” Miller said, adding that in the process of collecting political buttons and other historic items, he became “kind of a specialist on Bobby Kennedy.”

A large part of his collection also included black civil rights imagery, some samples of which are on display at the Psychedelic Shack exhibit.

It may be the musical and technical angle of the installation, however, that best represents Miller’s interests and expertise, and he got an early start acquiring experience.

Miller recalled growing up in Pine Bush as a first-generation American of Czech descent and said he “felt like records were my only friend because the kids I knew were miles away by bike.”

Summers he communed with Brooklyn youth whose families rented cottages in the area, and “a lot of music was played.” Miller played drums in makeshift bands, developed an interest in the technical aspects of music and acquired headphones and some modest equipment with money he earned delivering newspapers.

In high school, he began working at radio station WALL in Middletown, NY under the tutelage of dee jay “Cousin Brucie,” Bruce Morrow, who bought the station with Robert FX Sillerman.

“I learned a lot from him,” Miller mused.

One of the things he learned was that he wanted more than “knowing what he was going to say every six minutes.

“I got into radio because I loved music and I knew I would have to speak,” Miller said, explaining that years of speech therapy in public school motivated him to find work that would continue refining his speaking skills.

“Radio guys were ‘the voice out there,’ kind of mystical,” he said, so he started “hanging out with a late-night deejay,” then landed a job.

“It got boring though,” he said. “It was a lot of ‘rip and read’.”

His next career stop from 1980-86 was stand-up in Hudson Valley clubs, opening for the likes of Twisted Sister and other bands.

“I worked days at “any [radio] station where I could go to New York [at night] and learn to speak extemporaneously,” he said.

It was at one of these gigs that he was “discovered” by a music industry representative.

“The guy said, ‘Ever think about getting into the music business?” Miller recalled, so he interviewed at Atlantic Records in February 1986 and got a job, the duties of which were: “Get the records played!”

Promoting bands such as INXS, Yes, and many others, Miller described the job as “highly competitive” from the 1980s to the early 2000s, when radio was still a huge market and the “record business was bigger than the movie business.”

During his 30-year tenure in the industry, Miller rose to an executive position at Virgin Records, Sony Classical, and RCA Victor. In 2006, he managed the merger of Sony and BMG, where he helmed the venerable MASTERWORKS label. Among his career accomplishments was working closely with what he described as “the world’s most talented artists from rock to opera.” Big names included Iggy Pop, Lenny Kravitz, Plácido Domingo, Yo-Yo Ma, Harry Belafonte, and Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi.

“One of my proudest achievements was signing [them],” he said, but admitted that amidst the high-pressure demands of signing and promoting some stars, he may have discounted the talents of others.

“I focused on the business aspects of music and [regrettably] was prejudiced against entire musical genres [because they were competitors],” Miller confessed.

After retiring, however, and having the time to listen to artists he had formerly dismissed, Miller had something of an epiphany. “The Allman Brothers, for example, were –wow—so innovative when I sat down and really listened,” he said.

Consequently, perhaps, “really listening” is something Miller now does a lot and encourages others to do, as well. During the pandemic, he converted a 12X20-foot room in his home as a listening studio.

“All that’s allowed is listening,” he said, adding that during his time promoting musicians for different record labels, he had to be “an active listener” in order to find an audience for his clients; he couldn’t afford himself “an analog experience with music.

“Music really does come off differently through earbuds than it does in a space,” he asserted. So, when the installation space is quiet, it becomes a sound stage where Miller positions a quality stylus in the grooves of a well-maintained LP and sits back to listen and appreciate.

Miller has lovingly researched and maintained an impressive vinyl collection, which expanded when he moved from New York City to Gloversville in 2020 and learned that Decca, which became Universal, printed records in the small city. The president of Decca Records from 1956 to sometime in the 1970s, he said, was Gloversville restaurateur Dick Johnston of Dick ‘n’ Peg’s Northward Inn.

In the last five years, Miller has “become fascinated with record making” because of Gloversville’s connection with Decca. Concomitantly, he has developed a keen interest in vintage record-playing equipment, some of which can be viewed at the Psychedelic Shack show.

“The octogenarians who know how to rebuild this stuff” are gradually dwindling, he lamented, so he has become “self-educated.”

Miller said he began repairing and upgrading turntables when he left the music industry in 2012 but did not have a sound system in his home because of the time demands of the industry job.

He subsequently got equipment out of mothballs and began learning the mechanical and electrical end of sound reproduction.

“There’s something really wonderful about doing something with your hands,” he said, adding that he had to learn soldering and electrical work, keeping him not only manually but “mentally fit.”

The idea for the Psychedelic Shack installation was born after Miller joined the Glove Cities Arts Alliance in 2021, both to support the fledgling organization and to nurture his love of the arts. About three years ago, discussion included compiling artifacts from several people’s collections, but due to delays and other factors, Miller emerged the lone supplier and curator, he noted.

As for future ventures, Miller said, “I’m really attuned to sound now.” He would like to offer his abilities and knowledge to businesses which struggle with acoustic issues or which need sound design. He also hopes to sell quality audio equipment, repair and upgrade tube amplifiers and possibly contribute to more installations.

His interest in politics and social issues will remain strong, too, as well as a sense of patriotism, he intimated. “I feel lucky that my family made it here [the U.S.A.],” he said, looking around at samples of his political and civil rights memorabilia.

“Initially, I collected anything that had an American flag,” he added, “but somehow I think we have lost the flag as a liberal emblem… We were able to get through these assassinations [of the psychedelic era] though, and I think there is still love and hope. It’s too soon to give up.”

Comments are closed.