Earlier this month, Bob Dylan made waves with the publication of his long-awaited critique of 66 of his favorite tunes by other songsmiths, The Philosophy of Modern Song. Now veteran music journalists Marc Myers and Steve Baltin are weighing in with their own fascinating and divergent explorations of this turf, with Anatomy of 55 More Songs (Grove Atlantic Press) and Anthems We Love (Harper Horizon).

Unlike Dylan’s book, which doesn’t delve into the paint-by-numbers makings of the classics, Myers and Baltin’s approaches are straightforward explorations of the creation and lasting impact of some of pop’s most iconic compositions. Where Dylan often employs his selections as jumping off points for impressionistic, very personal essays about the subject matter of his chosen songs (divorce, career crash, gambling, etc.), Myers and Baltin serve up approaches that are far more direct and satisfying, especially for music-makers.

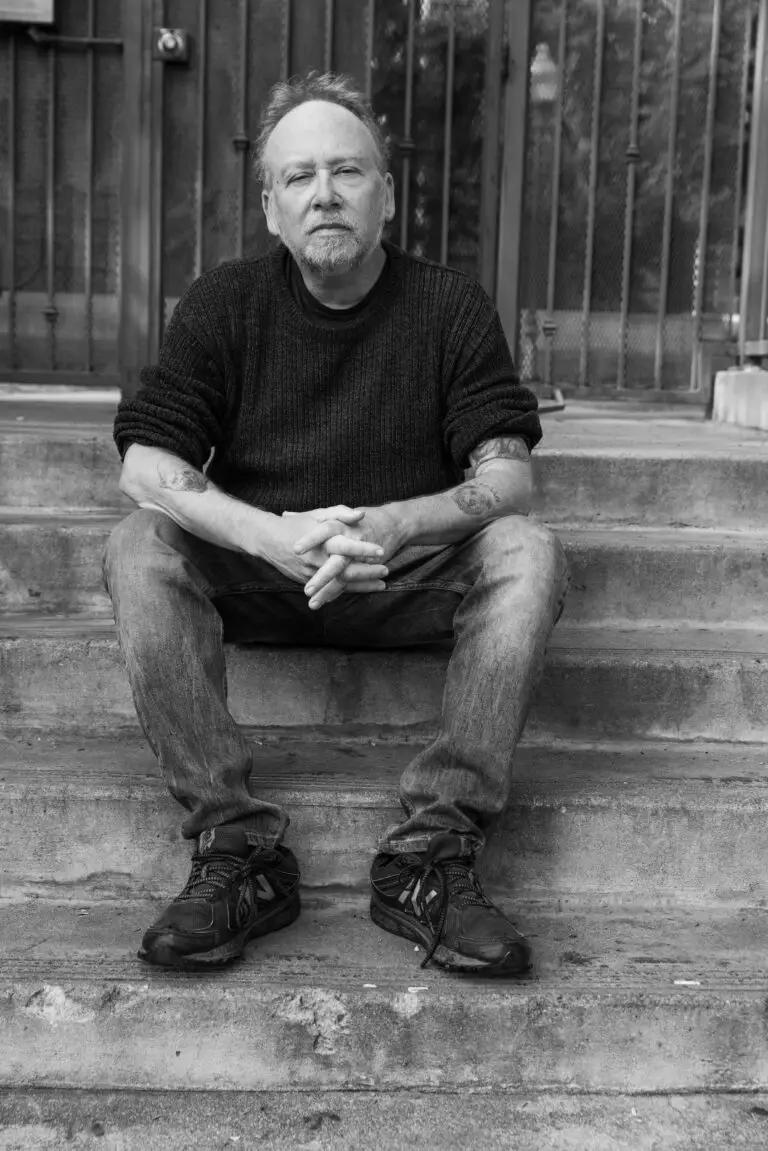

Myers’ newest is the second book culled from his long-running Wall Street Journal column, “Anatomy of A Song.” The first, a critical smash released in 2016, provided oral histories on the making of 45 era-defining hits from interviews with the artists that crafted them, names like Mick Jagger, Jimmy Page, Stevie Wonder, Joni Mitchell, Rod Stewart and Roger Waters to name a few. Myers’ latest takes on 55 more including Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Bad Moon Rising,” The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid,” Joan Jett’s “Bad Reputation,” The Spinners’ “I’ll Be Around,” Blondie’s “Rapture,” Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman,” The Youngbloods’ “Get Together” and Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

In his interviews with the songwriters and collaborators like producers Tony Visconti and Bob Ezrin, Myers brings you backstage for an incredibly detailed view of their inspirations and creations. These are engaging narratives that are dressed up with offbeat trivia that will make you the star conversationalist of any cocktail party.

John Fogerty tells how his “Bad Moon Rising” was a marriage of the short story, “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” and Scotty Moore’s guitar licks on early Elvis records. The secret sonic sauces? He did it with his Les Paul tuned down to D and slapback echo on the vocals that make everyone think his final lyrical couplet may be “there’s a bathroom on the right.” The latter is something Fogerty now periodically deploys in concert to the amusement and delight of his audience. The versatile Todd Rundgren shares how his twice-recorded “Hello It’s Me” may not have come to be if his high school girlfriend’s dad hadn’t turned the garden hose on him for having long hair or if he hadn’t heard jazz organist Jimmy Smith’s version of “Johnny Comes March Home.” Tommy James and the Shondells’ “Crystal Blue Persuasion” was not an “acid song” as many believe. It was something inspired by a poem put in James’ hand after a college gig by a kid who was never heard from again. Bob Weir of The Grateful Dead shares that their “Truckin’” really crossed over largely because of the harmony tricks they had picked up from jazz great Jon Hendricks. As for AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell,” it also was almost not to be when the cassette containing the rough rehearsal demo became unraveled and was nearly destroyed before they could share it with producer Mutt Lange.

Shock rock pioneer Arthur Brown’s hit “Fire” sprang from a poem he had written at 15, while Steve Miller’s “Fly Like An Eagle” only solidified after he added electronic trimmings from “the cheapest, dumbest synthesizer” he could find at his local music store. Steely Dan’s “Peg” only got its finishing touch when they wrestled the perfect guitar solo from session man Jay Graydon, the eighth musician to try his hand at it. Earth, Wind & Fire’s lyric collaborator Allee Willis never knew the significance of the date in their song “September” until years after leader Maurice White’s death (September 21 was the due date of his son as told by his widow to Willis). And even though she begged White 20 times or more, he would not replace the “ba-dee-yah” in the song’s refrain with lyrics “that made sense.”

Myers’ book also provides astute musical analysis that places the songs within the context of their time and meta musical trends. His chapter on Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” begins with a pocket history of power ballads of which this tune is a solid gold example. Myers’ traces the birth of the power ballad to days of movie musicals and Judy Garland’s show-stopper, “Over the Rainbow,” from The Wizard of Oz.

Where Myers is more focused on the big bang of their creation and immediate aftermath, Steve Baltin’s book is more focused on the reverberations – how hit songs with a unique staying power become anthems that connect with generations and have many lives beyond their time on the charts.

Baltin’s book investigates 29 iconic songs that have grown to anthem stature with the passing of time. These include everything from 60s classics like The Temptations’ “My Girl,” The Beach Boys “Good Only Knows” and The Doors “Light My Fire” to more modern rock and pop staples like Linkin Park’s “In the End,” My Chemical Romance’s “Welcome to the Black Parade” and TLC’s “No Scrubs.”

To become an anthem a song needs two things per Baltin – timelessness and universal appeal. Most anthems are “mistakes.” Some like Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule The World” were throwaways that nearly didn’t get finished or recorded (it only was when Roland Orzabal’s late wife insisted that he decided to complete what he called his “rubbish song”). Others like Chic’s “Le Freak” were almost too silly in the minds of their creators, while still more like Graham Nash “Our House” were deemed almost too simple to be really proud of, even with their runaway success.

Baltin’s chapter on “God Only Knows” is a good template for his approach. While Paul McCartney and others called it “the greatest song ever written,” it was buried on a now-classic album that was largely ignored upon its release, Pet Sounds. Beach Boy Al Jardine compares it to “The Nutcracker,” a classical not pop production, something that its writer, Brian Wilson, also admits. He notes the “Tchaikovsky-influence” on his writing at the time. As with most of the entries here, Baltin goes on to note the many cover versions of the song (200 and counting for this one, from the likes of mellow crooner Andy Williams to art rockers Flaming Lips). He also completes many entries with a list of their frequent and very lucrative use in film, television and commercials.

In his chapter on Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline,” Baltin relates how this bit of sunshine pop from 1969 became a sports anthem for The Boston Red Sox and something that helped heal the city when Diamond performed it at Fenway Park five days after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick labels her “White Rabbit” a “rip-off of Ravel’s Bolero and Alice in Wonderland.” She credits its popularity to the “sex build up to climax” of the song’s arrangement. Interestingly, her favorite version of the song is not her own, but the one done by Pink – though she would still love to hear a cover by Barbra Streisand. In the same spirit, the Tears for Fears duo actually now prefers the downtempo electronica version of “Everybody Wants to Rule The World” recorded by Lorde for The Hunger Games: Catching Fire soundtrack. It’s an arrangement they sometimes perform in concert and have considered re-recording.

The only anthem in the book that was conceived as one was KISS’s “Rock and Roll All Nite.” According to guitarist Paul Stanley, the president of their record label, Casablanca, Neil Bogart, said to the band they were still struggling need an anthem to really breakthrough. Stanley went straight to his hotel room and penned the killer chorus which was fused with a partial tune by bassist Gene Simmons, “Drive Me Wild.” The tune did not really take off until it was re-recorded and featured on their 1975 live album, Alive.

The descriptions above just scratch the surface of these fine books, ones which belong on the bookshelf of any diehard music-lover and every music-maker seeking to capture lightning in a bottle.

Comments are closed.